A space for public opinion and debate, engaging with a broad range of contributors in architecture, landscape, urban design, planning, and beyond.

Most people call it crypto but for the purposes of this exercise we’ll use the term "blockchain".

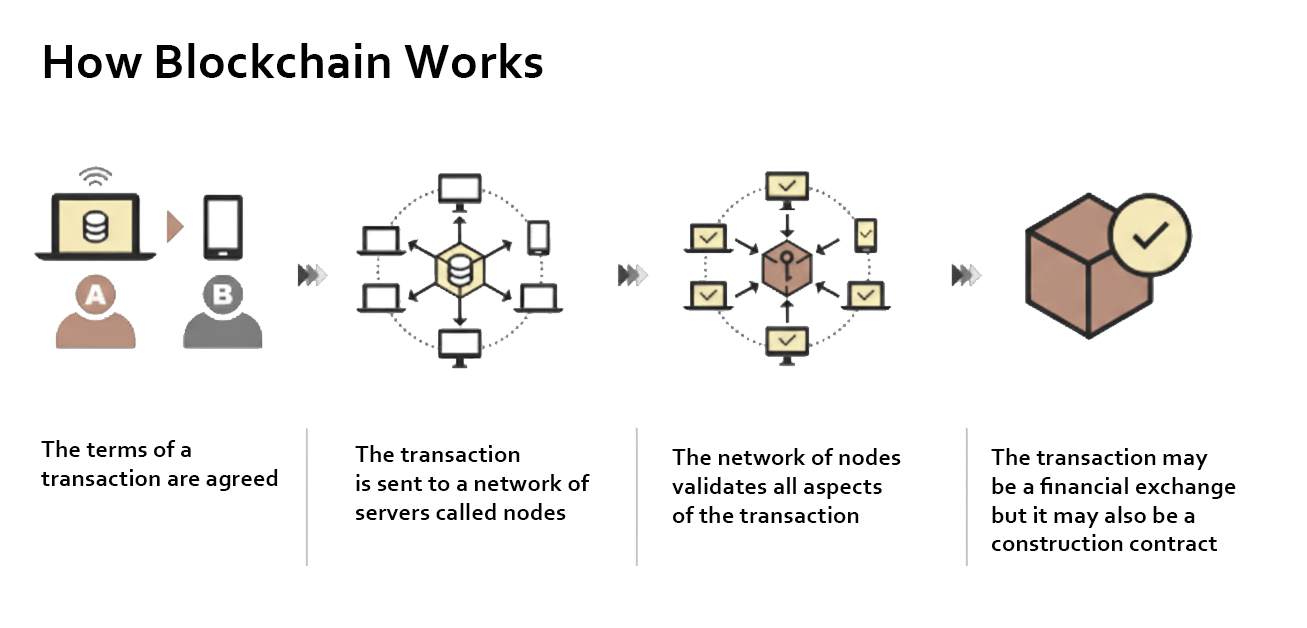

At its core, a blockchain is simply a way of recording an event on a digital ledger instead of in a paper document. This could, for example, be a record of an agreement - the kind of agreement people have been making between one another for as long as agreements have existed. If you do X, I’ll do Y. In the past, we’d make the agreement official by signing some papers in a solicitor’s office. However, with a smart contract running on a blockchain we take a different approach: first, we set out all the conditions that have to be met before the contract can be entered into; then, instead of asking a solicitor to decide when these conditions have been met, we write the whole thing in computer code and let technology act as the referee. The terms of the agreement are implemented without fuss and in a way that’s difficult to undo. If I suddenly get cold feet about some commitment I may have made, I can’t wriggle free of my obligations by finding loopholes and stirring up trouble. That’s the first interesting thing about a typical smart contract: terms and conditions are fairly hard wired.

The second interesting thing about blockchain contracts is the way details of the agreement are stored. Once the computer confirms that all the conditions have been met, the record isn’t just dumped onto one big central server which would be an obvious target for hackers. Instead, a copy of the entire record is kept on many different computers (nodes) spread out around the world. Each copy is kept in a series of linked “blocks” and each block contains a sort of digital fingerprint of all the verified information on which it is based. If someone tries to change even the tiniest detail in one block, the fingerprints won’t match and the change will be rejected. For extra security, large files (a good example for our purposes would be contract drawings) can be stored separately using a system like IPFS. The main block can be primed to keep an eye on these files to make sure that important material hasn’t been tampered with.

It didn’t take long for the earliest blockchain experimenters to see how this new technology could work as a form of money. Money, after all, is just another type of agreement. And so, around 2009, the terms "Bitcoin" and crypto entered the public imagination. Almost immediately, Bitcoin became synonymous with dodgy financial dealings and the internet was soon full of stories about international criminal gangs getting around banking regulations by paying each other in this new invisible currency.

But if we ignore all the hyperbole and look again at what an Ethereum-type blockchain involves – a system that has the same secure, tamper-proof data blocks as Bitcoin but also supports smart contracts – you can see how it might be used for things far beyond dodgy money. Anything that needs a secure, verifiable agreement could benefit from a blockchain approach, including many of the processes that underpin building and construction.

One of the more interesting examples so far of the use of blockchain in the broader construction/real estate space has been in property transactions and land registration. Anyone who’s ever bought a house, no matter where, will know that the process is slow, bureaucratic, paper-heavy and prone to error. Blockchain offers a secure, transparent alternative. In recent years Georgia (the country, not the US state), Dubai, Sweden and other jurisdictions have been testing out blockchain systems to record transfer of title. Media reports suggest the trials have been generally successful with transactions being completed sometimes in a matter of minutes.

In construction, the potential is just as easy to imagine. Take the example of a contractor completing the installation of a complicated foundation on a new project. Instead of waiting weeks for manual inspections to take place, on-site sensors confirm in real time that the work meets the agreed technical specification. That verification is automatically logged on a blockchain, which triggers immediate payment. Large companies like Skanska and Bechtel have been experimenting with these and similar approaches for quite some time, tracking materials from their source to their final installation as well as checking authenticity and compliance.

Another interesting area for potential blockchain crossover is the use of BIM. In a big public building project the architect, engineers and contractors might each start out working on the same 3D BIM model. But as the job progresses, each consultant makes one tweak here and another one there and soon various "official" versions of the same model have come into existence. When a dispute eventually erupts over whether a particular detail was formally approved, no one can be sure whose version of the detail is the “real” one.

With a blockchain-based approach, each approved version of the BIM model could be time-stamped and stored in a tamper-proof way so that a clear, verifiable record of what was agreed can be referred to. We could take this concept one step further and link the approved building model to a city’s digital twin – say, Dublin or Cork – with the building’s latest data slotted straight into the digital city model. This would mean that planners, utility providers and emergency services would have a reliable, up-to-date digital version of the building to work from. And, in fact, this is something that is already being explored in Dublin where the City Council’s partnership with DCU on creating a digital twin has received favourable coverage in the trade press.

While there has been progress in these and other areas, particularly in the private/commercial sphere, wide-scale adoption of blockchain technology in the worldwide construction industry faces a number of hurdles. For a start, regulations vary widely from region to region, making international coordination difficult. Added to that, the technology’s reputation still suffers from its early association with international criminal activity and, more recently, its environmental credentials have also been called into question. Similar to the technology involved in AI, conventional blockchain technology depends on large, power-hungry infrastructure which raises legitimate concerns about energy use and environmental impact, although it must be noted that more recent developments in the field have significantly reduced the amount of electricity to power an Ethereum-type chain.

In Ireland, there’s the added challenge of slow adoption in the public sector. The Government’s recently revised National Development Plan makes passing reference to AI, but none to blockchain. And while some of the important crypto exchanges like Coinbase and Kraken have an established presence in Dublin, there isn’t a sense that blockchain technology has made an impression on the national psyche just yet. Without a clear strategy at government level, we risk falling behind countries already using the technology to speed up land transactions and improve on the construction workflow. How a more streamlined AI/blockchain approach could improve the delivery of, for example, much needed public housing is an interesting point to consider.

This doesn’t mean we should simply bemoan our misfortune and sit around waiting for the next tech opportunity to come our way. One of the more interesting things about the rise of AI, taken in its broadest sense, is its ability to tackle problems that feel too big or too unwieldy for heavy bureaucracies to sort out. So there’s no reason we couldn’t use AI to help us work through the practical and policy challenges of bringing blockchain into our construction and property systems. If we could get the two technologies working together – AI to design streamlined processes, blockchain to guarantee their integrity – the results could be extremely positive for everyone involved. And the countries that manage to combine AI and blockchain in this way will almost certainly enjoy some real advantages. There’s still an opporutnity for Ireland to put itself out in front – but time is running out.

Blockchain can offer a secure, transparent way to record agreements, and therefore holds potential across construction and property sectors, enabling real-time verification, automating payments, and improving data reliability. Yet its adoption in this context remains limited. In this article, Garry Miley discusses the possible impacts and limitations to the technology’s implementation.

ReadThis year’s presidential election made visible a dynamic that is often overlooked in political analysis: how campaigns operate as a form of civic infrastructure, and to what extent design plays a role in their efficacy. Far from being peripheral or decorative, the visual strategies deployed by candidates’ structure how people encounter political life; they shape perceptions long before policy is discussed or manifestos are read. Political design occupies a unique position within democracies, somewhere at the intersection of communication, civic identity, and public trust.

In Ireland, this relationship between design and democratic expression has been strained by a decades-long pattern of executive neglect. Successive governments have systematically deprioritised design and aesthetic quality in public communication and built infrastructure. Senior ministers increasingly frame design as an optional consideration, an unnecessary add-on rather than a fundamental part of how the State articulates care, competence, and regard for its people. As Minister for Public Expenditure Jack Chambers stated during a debate concerning escalating costs at the National Children’s Hospital (NCH), ‘there needs to be much better discipline in cost effectiveness… That means making choices around cost and efficiency over design standards and aesthetics in some instances’ [1].

This position, widely cited and contested, exemplifies a broader ideological shift which sees design treated as a dispensable luxury rather than an essential civic tool [2].This framing misunderstands the function of design within public life. Design, in this case, is not ornamental; it is a mode of communication through which the State makes itself legible. When design is neglected, the consequences extend far beyond the aesthetic and shape the conditions under which political meaning, public trust, and civic visibility are formed.

In the aftermath of Catherine Connolly's election as President, commentators highlighted the design and visual expression of each candidate as decisive factors [3]. Connolly’s campaign offered me a rare opportunity to explore what an authentically Irish political visual identity might look like when grounded in cultural memory rather than branding for the sake of visuals alone. While designing, I drew directly from Ireland’s vernacular signwriting tradition: the hand-painted shopfronts, gilded fascias, and serifed letterforms that once defined the visual texture of towns and villages. These were not simply aesthetic references. They embodied authorship, locality, and a sense of civic care.

By incorporating hand-drawn lettering, a deep green and cream palette, and a postage-stamp motif, the campaign sought to restore the tactile warmth and humanity often lost in contemporary political design. The stamp, a quiet symbol of communication and exchange, is a reminder that politics is, at its core, a conversation carried between people. This concept frames Irish craft traditions not as relics, but as living cultural practices capable of shaping contemporary civic discourse.

In doing so, Connolly’s campaign made design itself an act of cultural continuity, a way of honouring the past while proposing a more grounded and participatory future. By the time Connolly declared on election night, “This win is not for me, but for us,” the sentiment had already been woven through posters, leaflets, and social media, a visual testament to a campaign that made the collective visible long before the votes were counted [4].

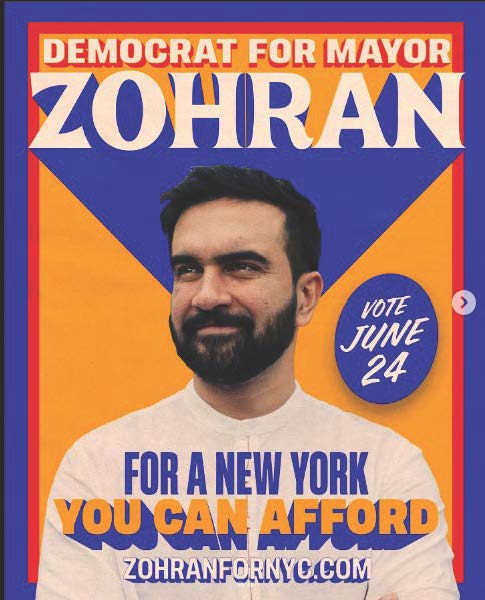

Across the Atlantic, Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral campaign in New York City attracted attention first for his democratic socialist views. It was the striking coherence of his campaign design, however, that propelled him into broader public discourse. Not since Shepard Fairey’s Hope poster, for Barack Obama, had a political image circulated so widely. It gained the kind of immediate recognition associated with Jim Fitzpatrick’s image of Che Guevara.

The Mamdani campaign was intentionally rooted in the material and cultural vernacular of the city itself. The cobalt blue and yellow palette was drawn directly from everyday sights in New York: bodega awnings, taxi cabs, MetroCards, hot dog vendors, and the signage of small independent businesses [5]. In this way, the campaign aligned itself with working-class infrastructure that defines the city’s public life, situating Mamdani not as an outsider but as a candidate embedded in the city’s social, cultural and economic rhythms [6]. Central to this strategy was the premise that design could serve as a communicative bridge to the constituency Mamdani sought to represent. In doing so, the campaign framed visual culture as a mode of continuity and care, a reminder that political communication can affirm belonging as powerfully as it persuades.

Irish election materials, as well as the State's political design more generally, don't attempt to convey substantive meaning through visuals. Their long-standing reliance on formulaic portraiture, generic slogans, and minimal graphic refinement mirrors a broader campaign strategy in which candidates are packaged as approachable local figures using highly-conventionalised visual cues. This approach reduces design to a mechanism for name recall rather than a vehicle for articulating political values or fostering civic engagement. The environmental waste associated with poster production only heightens the sense of outdatedness and underscores how Irish campaign materials often lag behind the more considered, narrative-driven strategies emerging elsewhere. As such, this tradition of visual identity crystallises the limitations of Irish political branding: a dependence on repetition, familiarity, and low-risk aesthetics at the expense of meaningful visual communication.

A strong democracy depends on sustained, accessible dialogue between the State and its people. Visual identity is structurally embedded within this exchange. Visual languages that are familiar or culturally resonant reduce cognitive load and strengthen affective engagement, whereas generic or stylistically flattened forms tend to weaken meaning-making [7]. In this sense, campaign aesthetics function as a form of civic infrastructure, shaping perceptions of authority, intention, and legitimacy before a single word is spoken.

When design is framed as a luxury rather than an essential component of civic life, it erodes the shared visual language through which democratic communication occurs. Such an approach initiates a feedback loop. Minimal investment in design yields fewer meaningful symbolic or material expressions of public life. As these expressions diminish, the State becomes increasingly illegible to its people. Over time, the corporeal presence of the State, its visibility in the everyday, degrades. What was once a free-flowing dialogue becomes generic, flattened, and emotionally inert. Political branding therefore mirrors the State’s broader orientation toward public infrastructure. When design is treated as secondary, a dispensable aesthetic layer rather than a civic medium, its communicative and democratic potential collapses. When taken seriously, however, design becomes a point at which cultural belonging, political intent, and civic participation converge.

Ireland’s future civic health depends not on dispensing with design but on recognising it as a central component of public life. It is the medium through which the State becomes visible, legible, and trustworthy.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Highly visible and emotionally charged, electoral campaigns are often the first instance in which a state’s people encounter their elected representatives. In this article, Anna Cassidy, designer for Catherine Connolly's presidential campaign, examines how political design is indispensable to the democratic process.

ReadEffectively a continuous zoom call encased in a three-metre tall stone frame, the portal arrived with a promise of diasporic fraternity and a message of shared humanity borne out of access to the same ‘liveness’. The project is regularly described by Gylys in profoundly optimistic, even techno-utopian terms: ‘I felt a deep need to counter polarising ideas and to communicate that the only way for us to continue our journey on this beautiful spaceship called Earth is together’, and later as ‘The addition of the Portal in Philadelphia is an exciting step forward in our mission to build a bridge to a united planet’. [1] This sci-fi language of ‘spaceships’ and ‘missions’ – that suffuses all publicity released by Portals Organization – seems to reveal that for Gylys, the specific urban contexts in which the portals are located are secondary in importance to the fact that cities have dense populations, and can therefore bring a maximum number of ‘fellow humans’ into remote contact.

There is generosity in this goal. While Gylys may be operating from an idealised stratospheric viewpoint, the installations themselves are nevertheless embroiled in the fabric of urban life – in the politics of real estate, and bear witness to the endlessly contingent cityscapes they exist within. [2] Insofar as they present an image that is truly ‘live’, they live among us.

In fact, their circular viewport, coupled with their stationary nature, means that the portals share something of a cultural lineage with a much older technology of civic novelty: the camera obscura. Particularly the popular Nineteenth-Century camera obscurae that were built to be public attractions on high vantage points in cities like Bristol or Edinburgh. When spending time with the images cast by both, the presence of a hypnotic and uncanny liveness – an endless, voyeuristic potentiality – can make it difficult to look away for fear of missing something.

The portals differ from these darkened rooms however, because unlike the rarefied, sanitised views offered by these constructions they address the street at just above eye-level. In Skyline: The Narcissistic City, cultural historian Hubert Damisch outlines a divergence in the historical representation of urban space between ‘birds-eye-view’ depictions and maps that abstract and seek to rationalise cities – ‘Does the city remain “real” when considered from such distances [...]’ – and street-level depictions that present urban space as lived, contingent, and personal. [3] Damisch argues that the perspective techniques used by the painters Canaletto and Brunelleschi to produce realistic veduta paintings imply and demand a subject. [4] Veduta means ‘view’ in Italian, and there is no view without a viewer.

Camera obscurae are distinctive today for their relative stability. Unlike ubiquitous jittery smartphone video feeds, a camera obscura will generally remain still, allowing the world outside to move silently past within its static frame. A decision therefore needs to be made about what its aperture should be trained on. Will there be enough movement and visual interest from this or that vantage point? There is a politics of performative urban representation implied in this decision. What kind of scene, what view of ourselves and of our space justifies the building of a camera obscura? A similar value judgement applies to each portal.

Many Dubliners were initially bemused and apprehensive at the choice of location on North Earl Street. Sitting in the afternoon shadow of The Spire, and across the road from the GPO, it is placed in a historically significant part of the city, but also an area – ‘D1’ – that is notorious among locals for its high concentration of social issues. There was much talk at the time of; ‘why we can’t have nice things’, and the early weeks of the portal saw enough of what was deemed inappropriate behaviour from both cities to generate a viral international interest in the portal, and a temporary suspension of its video feed.

It is significant that it was placed in the heart of D1, rather than an alternative, more predictable cultural hotspot. Since its installation planters have been placed immediately in front of the screen, to create distance between the portal and the crowd, and the steady stream of visitors to the portal appears to be bringing a form of passive communal surveillance to the street, along with bringing custom to the area. Regardless of the location choice however, the important thing is that the portal greets us where life happens, at street level, rather than from on high. For this reason, and despite its sci-fi billing, it enacts a useful resistance to a pervasive trend in tech ideology to operate inter-planetarily, agelessly, and it ends up doing something simple – it enables eye-contact.

We’re looking at a street-level view of somewhere in the UK.

A woman in a black knee-length jacket does a shimmy dance in the centre of the circular frame while a group of tourists film her from our side.

Someone is on their phone waving into the screen, someone on screen – also on a phone – waves back.

We’re in Poland. But this camera angle seems to be more buildings than pavement and there’s no one in view.

Then, suddenly, we’re in Lithuania. An empty square, wet cobblestones and white street lines stretch off towards a grand seeming civic building.

There must be more than twenty people gathered here in the rain at this point, James Joyce’s hat and glasses standing only just taller than the cluster of black umbrellas.

The square is still empty, a man with a dog on a lead walks through the centre of the frame from left to right.

A young woman and man emerge from the bottom of the frame and turn to us while on the go, waving their bound umbrellas at us as if afraid of appearing rude.

It feels like we should see ourselves on the screen, as if we were taking a group selfie. We sense that we are performing, but we disappear at this end.

Lithuania is busy now. It is wet there too.

Three people here have not moved from their position at the front since I've been here. It feels like they are waiting for someone.

On our side a woman in a red velvet dress with a black umbrella pirouettes and curtseys while on her way into North Earl Street.

A seagull sits atop the portal.

In May 2024, the Lithuanian artist Benediktas Gylys installed a portal between Dublin and New York. In this article, Felix Hunter Green explores how the portal (the third of its kind at the time) introduced a new form of present tense, a remote urbanism, to the fabric of North Earl Street.

ReadThree seemingly unrelated stories caught my eye in the news in recent months. In the Dublin suburb of Dundrum, residents spoke out in opposition to a proposal to build an “aerial delivery hub” in the centre of the town.[1] A meeting organised by local politicians was attended by the chief executive of the drone company, but this wasn’t enough to convince the citizens of Dundrum that the new hub was a good idea.

A few weeks earlier, Irish billionaire businessman Dermot Desmond was reported as having described the long-awaited Metrolink project as obsolete and “a monument to history”.[2] He argued that autonomous vehicles operated by artificial intelligence would make the rail line redundant, would cut the number of vehicles on the road dramatically, and eliminate congestion. His argument was dismissed by transport experts and citizens alike.

More recently, in the annual scramble for housing, students in Galway spoke in despair about the lack of available accommodation, noting that there are currently over 1,000 properties listed on Airbnb for Galway, while there are only 111 properties to rent on Daft.ie (in fact, the figure maybe below seventy).[3]

What these three stories have in common is that they are all underpinned by technologies which aim to minimise social interaction within our cities, based not on a desire to provide a service to society (whatever their proponents might claim), but to extract maximum profit by eliminating the cost of people doing real work.

Canadian writer Cory Doctorow coined the term “enshittification” in 2022 to describe how online platforms switch from serving their users, to serving their business customers at the expense of their users, to finally serving only their shareholders, resulting in a poor service that both users and business customers are locked into. A similar process can be observed in the way technology is used to deliver services in our cities.

Airbnb is an undoubtedly useful platform for people looking for short-term accommodation for city breaks and holidays. When it was founded in 2008, it was celebrated as a means to connect individual travellers with homeowners who had space to spare, allowing users to bypass overpriced hotels and find affordable accommodation. On the face of it, this seems like a worthy endeavour, helping to connect people and to make more efficient use of available accommodation.

Fast forward seventeen years, and the impact of Airbnb on housing availability and on mass tourism is causing a backlash in cities across the globe. Barcelona plans to ban short-term rentals from 2028 in response to a housing crisis that has priced workers out of the market. New York City has introduced laws to restrict short-term lettings and block non-residents from letting out properties. Restrictions are also in place in Berlin, Lisbon, and Athens. Elsewhere, short-term lettings are highly regulated to limit over-tourism. Rather than connecting people, the rise of short-term letting has resulted in a sterilisation of parts of our urban centres where key-boxes proliferate and visitors never physically meet their hosts.

The plan for drone deliveries is just the next stage in a progression from takeaway restaurants doing their own deliveries, to online delivery platforms operating from dark kitchens. Again, it comes from a worthy pretext – to help restaurants connect with their customers and to make ordering takeaway food simpler for customers – but in this case, the enshittification stage results in streetscapes where restaurants no longer have a public presence, but are attended by gig-economy workers who act as intermediaries between businesses and citizens. The drone delivery concept goes one step further, replacing that human intermediary with a machine. The citizens of Dundrum certainly don’t see how that transaction is of benefit to them.

A similar progression can be seen from the redesign of our cities to suit the private motor car and the well-documented impact that has had on social interactions in the city, to the proliferation of ride-hailing apps, and now the notion that AI-powered driverless cars are the future of urban transport. Though the ride-hailing apps promised an end to congestion and reduced car ownership, the reality was very different – more congestion and more cars – and any system of AI-powered driverless cars will be governed by the same commercial imperatives to increase car miles on city roads. Again, where, in this, is the benefit to citizens?

A city is a community of citizens. At its core, it exists for the people who live there, and it thrives on social interaction. But what these technologies are doing, or proposing to do, along with things like self-service check outs, dark kitchens, and co-living units (which, despite their name, are fundamentally isolating environments), is to strip away that core. Removing human interaction in the name of efficiency and cost effectiveness is ultimately to the benefit of shareholders rather than citizens.

The Dublin city motto, “Obedientia Civium Urbis Felicitas” (Happy the city where citizens obey), has come in for some criticism recently. The Dublin InQuirer newspaper ran an unofficial poll earlier this year to choose a new, more appropriate motto for the modern city, and the winning entry changed just one word – “Participatio Civium Urbis Felicitas” (Happy the city where citizens participate).[4] That participation should be not just in the democratic functions of the city, but in the life of the city, in the culture of the city, and in the community of the city.

As we are assailed with technological solutions purporting to improve the lives of citizens, let’s consider them through the lens of the happiness of the city and its citizens. This is not a rejection of technology, but an acknowledgement that ultimately, technology should serve the citizens. If our cities are to thrive into the future, let’s recognise the importance of participation and prioritise measures that encourage social interaction and build social cohesion.

Ciarán Ferrie makes the case for more citizen participation in city life, culture, community, and democracy.

ReadScale in street-making is often a function of the objects or beings that a street serves, and a product of the time when it was designed and built. The medieval urban street would be narrow and tight if considered in the context of the width of a modern car - it was self-evidently designed for human-only occupation. Wide urban streets are a post-industrial phenomenon, but facilitating trade was not the only cause of expansion: for instance, the importance of the Dame Street-to-Dublin Castle route in 18th Century Dublin was emphasised by employing a wide-street design.1 Similarly, width was considered a vehicle for improving air quality and circulation, such as with Haussmann’s 19th century re-design of some of Paris’s most well-known avenues.2

The process of making new spaces, including urban streets, usually begins with a shopping list of needs and requirements which mix together to inform and produce a space of sufficient scale to balance a wide range of competing interests. Urban fabric generally thrives on the variety of scales and spaces produced by this process, which helps to ground the occupier in a sense of time and place. A number of Irish examples of wide streets, however, exist with a poor or at least muddled sense of human occupation.

Pearse Street is one such example. Originally named Great Brunswick Street, the street is a product of industrial expansion in the Dublin Docklands during the 18th century, and was renamed after Padraig Pearse in 1924. Its creation revitalised an area “hidden from the city by the bulk of T.C.D,” 3 and its width is an echo of the legal scale prescribed by the Wide Streets Commission in the Act of 1758, even though it was never an original target. It was, put simply, an urban trade route from the delivery point to final destination.

It is approximately 1.2 kilometers in length, spanning from Ringsend Road and the Grand Canal Bridge to the East, linking up with Tara Street and College Green to the West. At 19 metres wide, it is less than half that of O’Connell Street (49 metres). It consists of four lanes of one-way west-bound traffic flanked by two relatively narrow footpaths. It has few trees, central electricity poles or other vertical delineation, and mostly consists of low, slow-moving traffic and a high-level transversal Dart Bridge appearing at an angle from the upper storeys of the Naughton Institute of Trinity College. Walking it feels like hard work, with little to no changes in its surface materiality, landscaping or any other kind of visual variety to retain a wanderer’s interest along their way.

Much of the southern end constitutes the perimeter of Trinity College, with relatively little life at the street level, while the northern end is peppered with a number of vacant and closed off facades. It is telling that such a prominent street and transport node, with the benefit of south-facing facades, seemingly turns its back on the pedestrian. The root of the issue likely stems from an unpleasant and dangerous atmosphere created by the cacophony of traffic, but the removal of traffic in and of itself is not conducive to a successful street. It begs questions about what interventions can be done to reinvigorate this seemingly forgotten stretch?

Modern interventions to wide streets generally consist of two actions. Firstly, they can be subdivided with hardscaping and landscaping in an attempt to sequentially arrange the street occupation nicely for the human: if we move through a wide street like a series of mini streets and spaces, our interactions with the street will be easier; our understanding will be broken down and more easily digested.

O’Connell Street is one such example that has benefitted from spatial, visual and material compartmentalisation. The tarmac which is applied to the majority of the roadway is interrupted at the GPO, where a high-quality granite paving sett is used for both the road and footpath, emphasising the importance of that historic building and providing variety for the pedestrian. The width of the roadway is punctuated by a central pedestrian spine throughout, with all three pedestrian thoroughfares on the street organised around a variety of trees, old and young.

The success of such segregation would point toward a logic that streets designed for pedestrians should therefore be similarly organised. Such an approach, however, may diminish the original grandeur and scale of the street. It can prompt wayfinding issues by interfering with the visibility of landmarks that contribute to a sense of place inherent to a city’s fabric.4

The second option is generally to leave them to their original devices; the accommodation of vehicular movement. In an era where movement is dominated by the car, and the streets’ spaces are merely vehicular lanes, this makes for an element of the urban fabric, which is unfriendly and, frankly, unoccupiable.

“First we shape cities, then they shape us.” 5 Pearse Street was – finally - recently the subject of a Dublin City Council decision to restructure traffic routes, with the removal of cars approaching from Westland Row. This, hopefully, is the conclusion of the previous indifference it has suffered from - now that space for cars has been diminished, human-centred urban interventions, with a particular emphasis on variety in all aspects, should follow suit.

In this article, Laoise McGrath reflects on the challenges presented by wide streets, the prioritisation of cars over people, and the potential for more inclusive urban environments.

Read“[W]asn't this all started by some terminally online moron in trinity? … Nobody gives a shite so long as the statue isn't actually being damaged” wrote [Deleted] on the reddit page r/Ireland in a thread to discuss Dublin City Council's proposals to stop the repeated groping of the Molly Malone statue on Suffolk Street — her breasts repeatedly touched by the sweaty hands of tourists, so much so that the dark patina has been worn away to reveal the earthy metallic dark orange of the bronze from which the mythical fishwife was cast. Thousands of images of Molly #mollymalone circulate on TikTok. A group of men dressed in Jack Chalton-era Irish football jerseys stand in line to rub their faces in her breasts. In the comments section one user posts, “reminder she’s 15 in this statue,” others disagree, claiming she was older, as if somehow the behaviour would be permissible if the statue represented Molly as 17 – the legal age for consenting sexual acts. Others use the platform to protest the behaviour.

If you ask Google’s AI Gemini about the practice, it tells you that “this practice is now discouraged by authorities for preservation reasons.” This is artificial stupidity, a view blind to a far more important problem, one that philosopher Sylvia Wynter described as an urban planning that assumes the male-coded subject as the norm, while others—women, Black, Indigenous, and colonised peoples – are excluded, marginalised, or rendered invisible [1]. For Wynter, urban space is ontologically male, in that its logics of design, governance, and belonging reproduce a gendered and racialised “Man” as the universal standard of being. Speaking to RTÉ Radio One, DCC Arts Officer Ray Yeates (a man) suggested that one solution could be to “just accept that this behaviour is something that occurs worldwide with statues” – human stupidity [2]. Perhaps Yeates might agree to a plaque being added, inscribed with a quote from Wynter: “Man …overrepresents itself as if it were the human itself”[3].

As images of the statue circulate online, they both promote and raise awareness of this deleterious practice. But this is the means and not the end of their circulation. These images turn Suffolk Street into a space for the production of a strange kind of economic exchange. With one sweaty hand on a breast, and the other on a smartphone, tourists become workers. Here, as in all of everyday life, a distinction can no longer be made between work and play. In our age of contemporary digital technology all of everyday life is a factory. To play is to work; the digital proletariat; to use a technological prosthesis is to be used by that prosthesis. These interfaces, designed for the many by and for the benefit of the few, manage life by means of ‘fun’. Spaces like Suffolk Street are, as Letizia Chiappini writes, where “[a]ffect, desire, pain, and love, are digitally mobilised for direct spatial impact” [4].

Henri Lefebvre called this abstract space – “[t]he predominance of the visual (or more precisely of the geometric-visual-spatial)” [5]. He described this kind of logic as a planetary mesh that has been thrown over all space [6]. Any space, anything, anywhere, no matter how banal is subject to this logic. 13,461 km away from the Molly Malone statue is an underpass in the Chinese city of Guilin. Each night crowds of outdoor live streamers gather to steam content on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), their faces glowing in the phosphorus white of selfie lamps. Geolocation means that if they are closer to more prosperous neighbourhoods then they make more money from the wealthy clients who live there. These leftover urban spaces that are seen as unattractive and once disregarded in a capitalist economy have become spaces where new economies and ways of working emerge. I have written elsewhere about the disproportionate role that Ireland plays in facilitating the infrastructures that produce these kinds of spaces [7]. This is a new kind of geopolitics, one facilitated by State fiscal policies, such as in Ireland, home of one of lowest standard corporate tax rates in the EU.

This is capitalism incarnate – capitalism become flesh. Everything has an exchange value. There is not a thing that cannot be transformed into a commodity to be circulated in an economy of flesh, thoughts, drives and desires. This is an economy governed by images, subject to what legal scholar Antoinette Rouvroy calls algorithmic governance – the governance of “the social world that is based on the algorithmic processing of big data sets rather than on politics, law, and social norms” [8]. The statue of Molly is a public surface subject to an extractive logic, via the lens she is engineered for constant circulation, interaction, and capture. The statue as code has her meaning flattened into content for the purpose of data extraction and ad revenue. This kind of collapsing together of work and leisure is a weapon of mass distraction. It removes us from everyday life, producing what philosopher Henri Lefebvre called a “transcendental contempt for the real” [9].

Lefebvre also called for a right to the city, by which he meant the right to the production of truly democratic space. Space that is not subject to capitalist abstraction. To what extent this is even possible in our precarious age of algorithmic governance is questionable - but nonetheless we must seek to understand, hope and act.

The groping of the Molly Malone in Dublin reveals a complex new urban condition – the algorithmic production of space. Social media, viral images, new modes of capitalist production, foreground the emergence of an entirely new logic of spatial production. What does this mean for the possibility of a right to the city?

ReadInterdisciplinary gatherings are rare, yet extremely useful because they allow people from various fields to meet, exchange information, influence each other's point of view, and to learn from one another in a way which is unique, unpredictable, and dependent upon the nature of participants field of discipline.

For various reasons, art and design-specific interdisciplinary gatherings seldom occur. Firstly, artistic occupations are generally quite competitive, so may prove reticent to share their processes. It is unfortunate as I firmly believe the more artists that one surrounds oneself with, the more one can explore their own process, even more so when it comes to an international gathering of artists and designers who would not otherwise meet.

Secondly, artistic communities are usually formed by a group of people interested in the same form of art, which is certainly beneficial when it comes to improving one’s technique. Nonetheless, learning from someone who is focused on a different discipline, thus confronting an unexpected perspective, is extremely useful. For instance, a painter and a fashion designer are both interested in colours: comparing their approaches can be eye-opening and thought-provoking for both. Being so rare, when people from various countries, disciplines, and professions do meet it is unforgettable and extremely enriching.

One such opportunity is MEDS, ‘‘Meeting of Design Students’, an annual international event that unites creative students from different fields together with practising professionals to share knowledge and skills and form meaningful connections through collaboration the medium of hands-on innovative projects.

A platform for creative and cultural exchange

MEDS is an international, non-profit, two-week event. Although adored by many international students, it is usually only through word of mouth that one gets to hear about it. This article is intended to raise awareness of this event, as it is a unique opportunity providing a wonderful and enriching experience both for students and young professionals alike to learn new skills and meet like-minded people. MEDS brings together students from various creative fields as well as professional practitioners to share knowledge and skills – “It promotes design’s positive societal impact, fosters interdisciplinary collaboration, and offers designers a platform to build connections, unlock potential and apply their talents outside the faculty” [1].

MEDS began in 2010 and has been held almost every year since. It has been hosted in a different country every year: Ljubljana, Slovenia in 2012, Dublin two years after, and Zaragoza, Spain in 2022. The event usually spans two weeks in August and gathers around 150 participants from all over the world.

To attend, one has to fill out an application form and complete a creative task. If selected, you become a member of a ‘national team’ including about 10 people from each particular country. Every participant chooses one of the proposed projects and spends two weeks working on it. The philosophy of MEDS rejects any hierarchy and so the tutors, who are open-minded professionals volunteering their time, and the participants develop and shape the project outcome together.

Projects / Workshops

This year’s Meds revolved around Rijeka, the ‘City of Textures’. All projects were typically hands-on, site-specific, and responded to the city and its context.

For instance, a project called ‘Urban Outf***ers’ led by Iva Mandurić, Vili Rakita, and Lea Mioković was an opportunity to design one’s outfit, a personal urban equipment, a public space survival kit to inspire and possibly shape one’s environment as soon as it’s taken off and left in public space. Something that was originally personal and individualistic suddenly became a part of public space to encourage interaction.

Anyone with a project in mind can become a tutor. A project called ‘Fialaigh’ (a veil, screen, or cover) was led by three TU Dublin graduates. All three, Christan Grange, Stuart Medcalf, and Shane Bannigan, studied architecture at Technological University Dublin and came to Rijeka to guide a project that was focusing on ‘themes of vacancy, occupation, value, and ephemerality, using spatial installation and film and the interface between them to interpret, capture, express, and let emerge narratives in our work’, as the tutors put it.

Had one wished for a building and construction-related project, one could have chosen from at least two options. The ‘Black Thought’ project proposed by designer Çisem Nur Yıldırım and the practising, Barcelona-based architect Alberto Collet involved building a sustainable wooden pavilion inspired by the Japanese technique Shou Sugi Ban. The other option offered rammed earth construction and tile production linked to themes of migration.

‘Plivatri’ and ‘Rječina’ were projects that designed public space interventions including a floating wooden platform for about eight people to hang out on, and pieces of public furniture made of scraps found on a trash pile for people to sit, share, and interact. Two of the tutors for ‘Plivatri’, Leda and Ahmad, met during MEDS workshop in Poland in 2021. Leda is a Cypriot designer based in the Netherlands, and Ahmad is a Lebanese architect and urban designer with experience across Europe and the Middle East. Leda later met Stephanie (a Romanian industrial designer) during their studies in Eindhoven. All three are passionate about alternative paths and collaboration across different disciplines and therefore teamed up as tutors.

Last but not least, three Warsaw Polytechnic students were the tutors of the ‘Pop Of Colour’ project this year. Although Mateusz, one of the trio, has just finished a Bachelor’s in Architecture, he is a graffiti artist himself. Inspired by numerous murals all over Rijeka as well as its industrial heritage and sea-side views, the task was to co-design and paint a mural on one of the walls of the local school gym, make a few pieces of simple furniture, and design a few playground games. The playground and gym remained open during the day allowing local children to pop in and observe the work in progress.

The MEDS community firmly believes in involvement with local communities, and therefore organises guest lectures to foster the connection between international students and the whole community. From friendships, collaborations, and professional networks, connections built at MEDS last long after the event ends.

Living the MEDS experience

MEDS is a purely student organisation run by students, recent graduates, and young professionals (once participants themselves) who make the event happen year by year, advocating for this broader, collaborative approach. The whole event is organised by a different national team every year and is heavily reliant on various sponsors. Accommodation is usually simple; participants and tutors stayed in the local school in Rijeka. Surroundings are different every year, but enthusiasm, curiosity, and creative energy remain. As places at MEDS are limited, there is luckily a very similar organisation called EASA (European Architecture Students´ Assembly). Following the same principles, it is mostly attended by architecture students however. MEDS is an international multidisciplinary event for art, design, and architecture students as well as practising artists, designers, and architects to broaden their skills and develop creative ideas.

Above all, it is a wonderful opportunity to establish long-lasting connections between people, disciplines, and cultures in a cross-disciplinary, collaborative environment..

Interdisciplinary gatherings, and particularly those of an artistic nature, offer a great opportunity to learn in unpredictable ways by bringing together creatives from diverse fields. In this article, Kristýna Korčáková explores how the ‘MEDS’ programme provides this chance.

ReadOur bodies do the work, do we think of them when they are working?

Feet ache from standing, backs tire from lifting, shoulders ache from poor posture at a desk. We sit down, stand up, take a break, take refreshment. In some workplaces, there is consideration of the worker and their body: canteens are provided, bathrooms are kept clean, and the ergonomics of a desk are contemplated. All of this relies upon the acknowledgement of, the visibility of, certain types of work and workers. If we turn our attention to the city as a workplace – specifically, the streets, thresholds, parks and pavements that make up the public realm in the city and that act as a place of work for many workers – how does it accommodate the bodies of workers? Is it hospitable?

Over time, the perceived value of certain types of work, and consequently certain types of workers, has fluctuated. When seen as essential to the economy, to growth, the needs and availability of workers are considered, and their ability to advocate for better working conditions is strengthened. This has occasionally resulted in an architecture that responds directly to workers’ needs. We might take the example of pithead baths, communal bathing facilities that were built close to coal mines in the early twentieth century. Here, miners could change and bathe; the dust and dirt of the colliery becoming the responsibility of the mine itself and not the worker and their home. In Architecture and the Face of Coal: Mining and Modern Britain, by Gary Boyd, we follow the development and eventual obsolescence of this distinctive typology, pointing to the transitory nature of coal mining as one of the reasons for the short lifespan of the baths and for their fading from view in histories of modernist architecture in Britain.[i] So we have an example of an architecture that springs up in response to workers’ needs, but that also mirrors the changing status of the workers themselves.

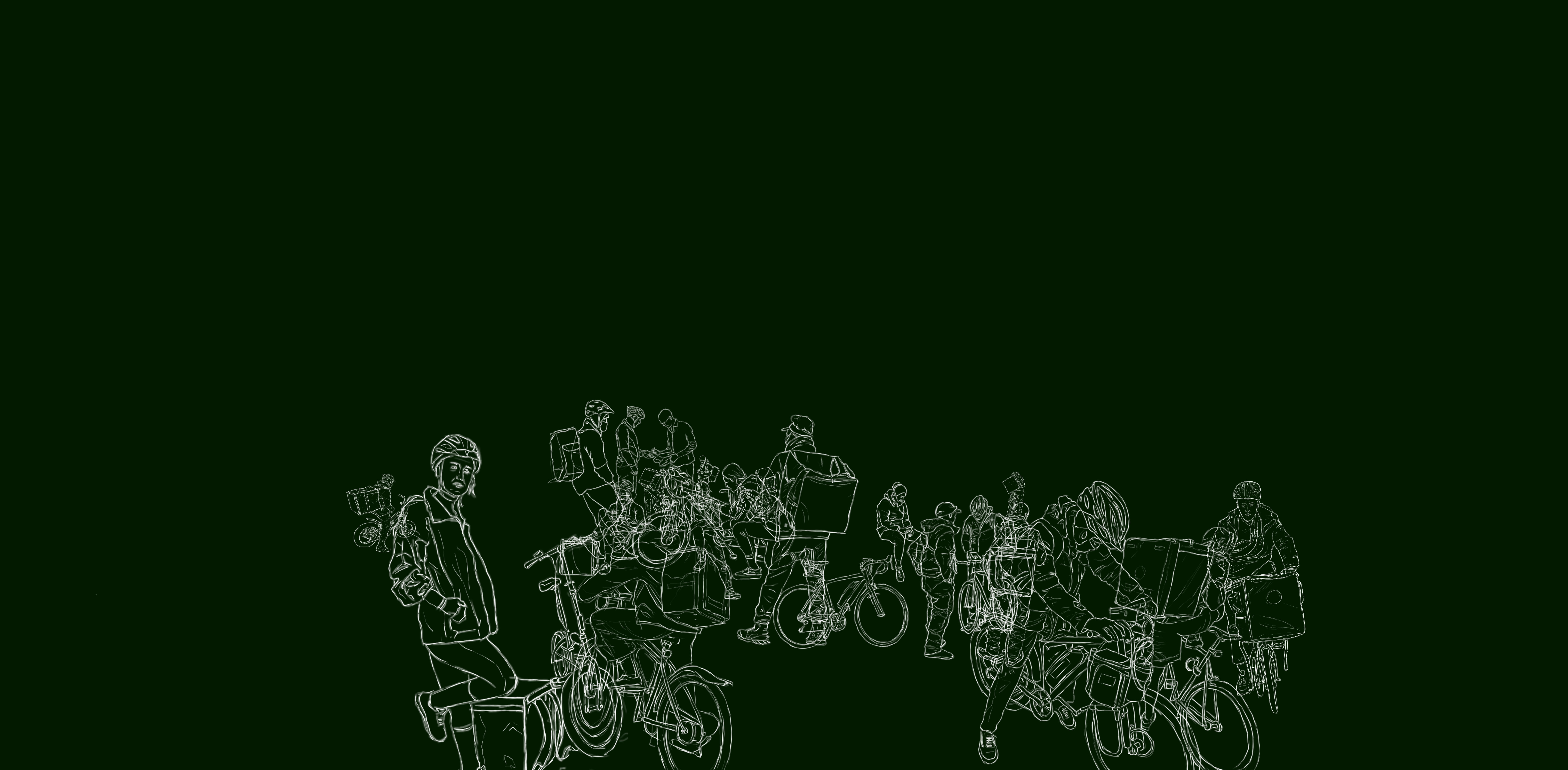

The value of different types of work is something that we continue to grapple with and that contributes to inequality locally and globally. Precarity is widespread.[ii] Nowhere is the daily reproduction of the worker more difficult and given less consideration than in the city workplace. A conspicuous example of precarious and disembodied labour is the fleet of food delivery riders that has grown in response to the evolution of online delivery platforms. This new virtual infrastructure has resulted in, but takes no responsibility for, a workforce that is reliant on the fabric of the city. While there has been recent media coverage of the riders' problematic working conditions,[iii] there has been less discussion about the pragmatic and bodily realities of their work, where they contend with weather, traffic, criminality and so on.

In The Practice of Everyday Life, historian and cultural theorist Michel de Certeau sets out a model whereby power structures are discernible by the “strategies” of agencies and institutions, representatives of the state or of commercial interests; the organising logic of city planning, for instance, or the virtual frameworks that map, track, and influence. Against, or within, these strategies are the “tactics” of the other; the citizen, the customer, or, to employ de Certeau’s preferred term, the user.[iv] If we pay close attention to the city workplace, we start to see the “strategies” and “tactics” at play, the creative and opportunistic ways of “making do” that individual riders employ in their everyday life: they rest against walls and railings; they take shelter under canopies and in ad hoc repair shops; they take shortcuts, crosscuts over rainslick tracks or in the narrowing gap between a bus and a van; they take risks;[v] they sit on park benches and at the feet of statues.

At O’Connell Monument:

Do you eat your lunch here?

“Yes, this is my office chair.”[vi]

A warehouse on Henry Place holds a rental and repair shop, renting primarily to food delivery workers. The building is a protected structure that is decaying as it awaits a contested redevelopment.[vii] A single open space is divided into two zones by a low plywood barrier: public (for rental) and private (for repair). Bikes stand ready. Metal shelves along the east wall hold the accessories that might be required by a rider. In front, a desk where forms are filled and rent is paid. In a corner, some sofas face a TV screen. A fridge, microwave and kettle provide basic facilities.

On Henry Place:

Do you take a break here?

“Yes, this is the only place that we are able to eat because we rent the bikes here, so they let us use the microwave, the refrigerator... This is the only place in the city that we can have a little space together to eat something.”

On this backland site, a temporary and informal responsiveness is demonstrated. The city user improvises on the ground, while elsewhere, a debate rages about value. In contrast to the windowsills and kerbstones that are often places of momentary rest for a delivery rider, a dilapidated and impermanent structure gives a sense of shelter and retreat, making space for camaraderie and some degree of bodily comfort.

On O’Connell Street:

Do the delivery companies provide any equipment or clothes for you?

“Not exactly, once in a while they give something for free, like the bag and the jacket, but not all the time. The jacket is more for promotion; it gets wet, you get wet anyway. We have to be careful because we can get sick most of the time, because the rain makes our bodies very cold. We have to be extra careful when it’s wet.”

Where previous communities of workers had their needs considered, as in the construction of pithead baths for miners, for example, it was possible to point to a single employer with responsibility for the welfare of their workers. Groups of workers could agitate and negotiate for facilities, for practical solutions to tangible problems. Emerging from a pit with body and clothing covered in black coal dust led to straightforward questions about washing, changing, eating dinner, and storing clothes during the working day. Improvements in conditions for miners were realised because these workers were together, situated, and visible. Another historical example of situated workers’ facilities was the series of green huts built by the Cabmen’s Shelter Fund in late-nineteenth-century London. The shelters provided hot drinks and food, a place to read the paper for cab drivers, answering a series of pragmatic, corporeal needs. Like many Victorian philanthropic efforts, they came with an undertone of self-serving paternalism. Now with a protected conservation status, a handful of shelters are still in use, the interiors remaining the exclusive preserve of cab drivers.

Today, in corporate[viii] settings, the body is considered in great detail. Ergonomic assessments are exacting in their appraisal of a body at a desk: the length of shin (footstool), the height of eye (monitor stand), the reach and range of forearm (vertical mouse). Training is provided in how and what to lift. In theory, an employer is responsible for assessing these risks to the body regardless of the location of their employee. But in an era of modern piecework, who cares for the pieceworker? And is there a parallel between the hands-offishness of employers and our attitude to city streets and passageways?

Delivery riders are visible in the city but untethered, distributed through the network of the streets, finding their own informal gathering places. They are not employees; they are independent contractors. This status allows them to be light-footed within a network of regulations and legalities.[ix] The subcontracting of accounts with various delivery companies, for instance, results in a grey market of official and unofficial riders. These tactics have their mirror in the ways in which riders improvise occupation of streets and pavements, and act, to a degree, on the city; they are limited, however, in how they might shape the city to their needs.

Emerging from a tradition that prioritises urban commerce and suburban living, we plan for the street as a thoroughfare, an artery, thinking mostly of flow, of efficiency. There is arguably a parallel prioritisation of the commuter worker within the workforce. Certain dimensions are assigned for cars and buses, for bicycles and pedestrians to move seamlessly from the city centre to the periphery. This diminishes the value of the urban realm as a place to be, to dwell. What if we were to see (or return to) the streetscape, the weather-world[x] of paths, gratings and doorways, of tarmacadam and streetlights, as a single, integrated space that hosts diverse needs and functions, including those of city workers? The sense of the city as a place to move through can be challenged by an ambition to make a hospitable city: a place of rest, shelter and conversation. Acknowledging the public realm as a workplace might prove a catalyst for an inclusive approach to city-making, considerate of all bodies and all work.

Our bodies do the work. In this article, Anna Cooke asks: do we think of them when they are working?

ReadBuried deep underground, encased in two and a half meters of concrete foundation is a copper scroll. A map of the night sky is engraved on its durable surface accompanied by the following declaration in five languages; English, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and Chinese:

“This building began on the 22nd day of November 1960 A.D. according to the Gregorian calendar. The planets in the heavens were as shown on this celestial map. The universal language of astronomy will permit men forever to understand and know this date.” [1]

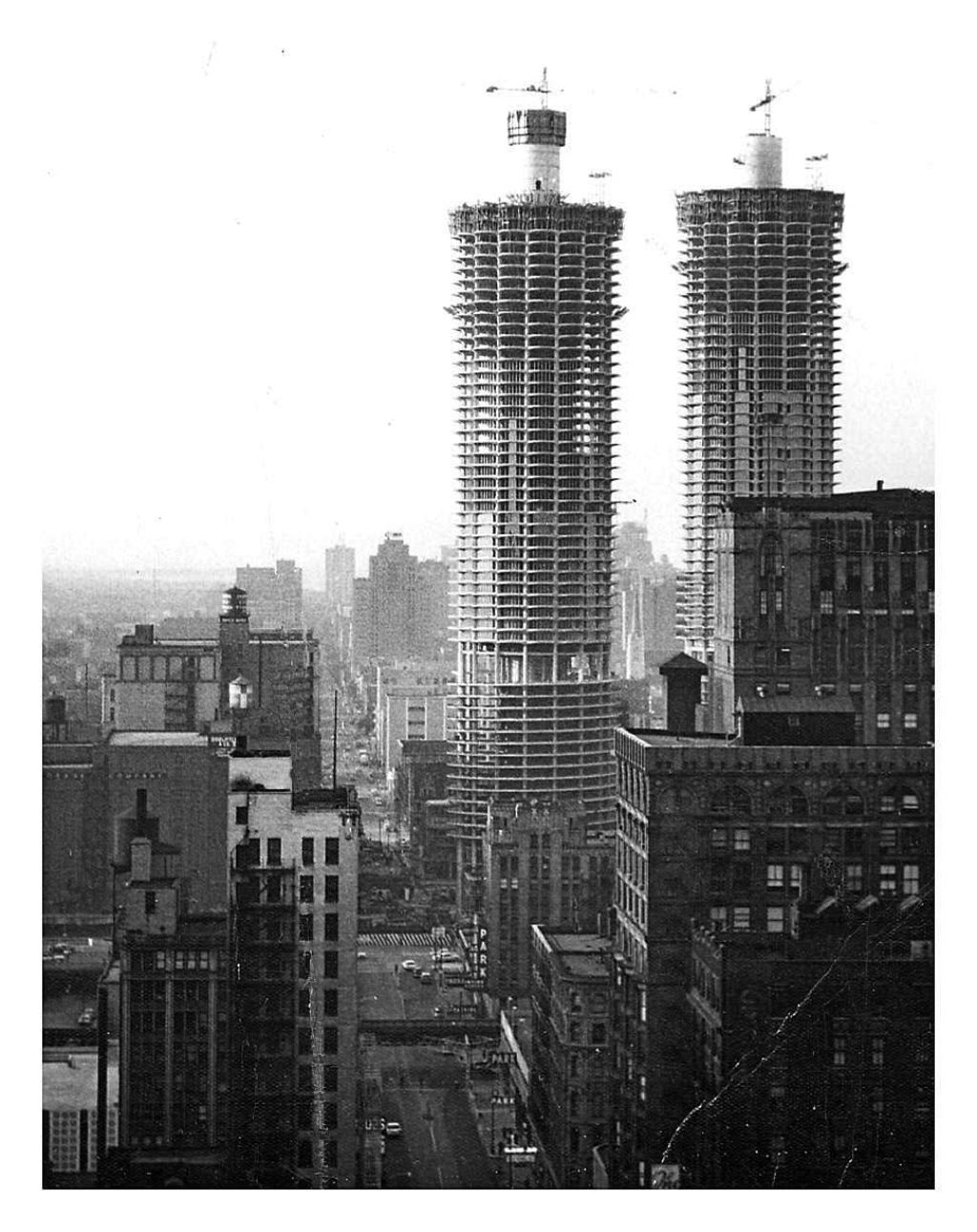

Replete with hubris and utopian optimism, Bertrand Goldberg, architect of Chicago's “Marina City” dreamt of a monument that would not only change the future of residential architecture but whose legacy may outlive its own material longevity. Forty floors above this map, overlooking the Chicago River, is my one bedroom apartment. However lofty Goldberg's ambitions, they did succeed in reshaping how many people live today, ushering in a new era of high rise living.

Marina City was the most ambitious residential project ever constructed in Chicago, crucially funded by Building Service Employees International Union seeking to reverse decades of “white flight”, the mass migration of white people from urban areas to post-war suburbs. Societal change, rather than profit incentives, was the primary driver of the project, and a radical solution to city living was required to sway public opinion in the immediate, and long term.

Conceived as a city within a city, the mixed-use complex accommodated a range of amenities including restaurants, a theatre, a bowling alley, and an office building within two 65 storey towers housing 1400 people, the tallest residential buildings in the world at the time of its completion in 1968. [2] Although dwarfed by some of its newer neighbours, they stand more than double the height of Dublin's tallest building at 179 meters, and are just shy of the Poolbeg Chimneys. As the first major mixed use complex in the USA, it inspired a boom of inner city construction that aspired to compete with the ease and amenities of the suburbs.

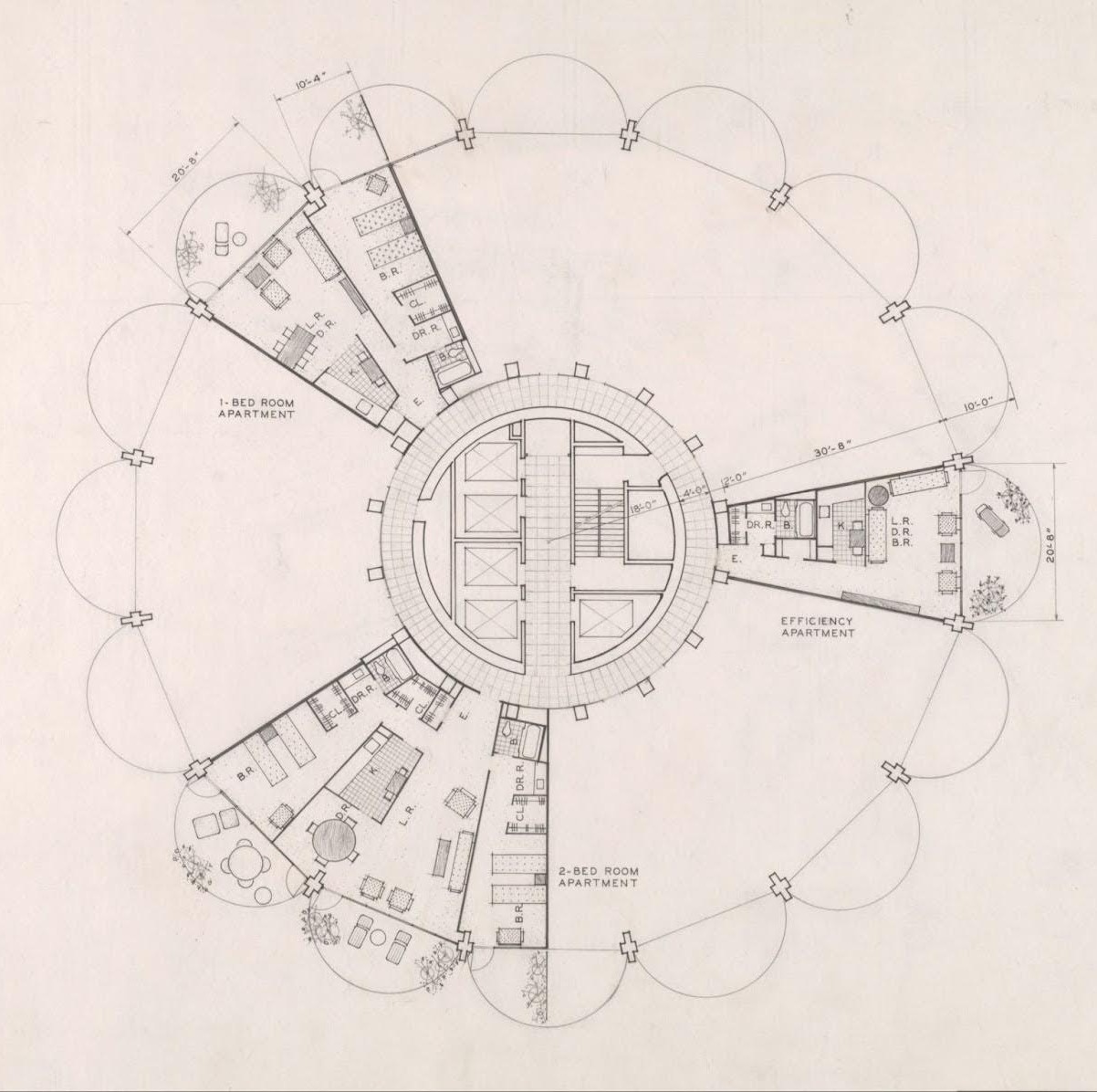

Right angles dominate Chicago; its unrelenting grid plan stretches for hundreds of square miles, and Marina City was a radical departure from the existing urban fabric. Once a student of Mies Van der Rohe, Goldberg broke from the rigid modernity of his former mentor, inspired by natural organic forms. The two towers share identical circular plans, rising from a spiralling base of open parking and topped with forty residential storeys. Each apartment radiates from the central core like a petal, culminating in a rounded balcony, giving the buildings their iconic flower shaped plan.

Creating lasting buildings also requires cultural sustainability, and the most sustainable structures are those that are appreciated. Marina City was immediately embraced by Chicagoans, becoming adored civic and mass media icons dubbed the “corn cob” towers. The towers appear tectonically simple yet sculpturally complex; a monolithic cast in-situ concrete frame with steel framed glazing slotted between, separating inside and out.

The structure holds the interior space, massive beams stem from the circular core, delineating living spaces. They sweep towards the floor at the building's edge forming columns, then arc into cantilever balconies in a display of structural grandiosity rarely seen in residential architecture. Completely rejecting Corbusier's free-plan, where structural elements can be completely freed from interior arrangements, here space and structure are in complete harmony.

Within this rigid frame is the flexibility to adapt to changing living standards. In our apartment, the antiquated enclosed kitchen has been opened up creating a single living space. The bathroom was enlarged and the black vinyl asbestos containing floor was replaced with a warmer hardwood. At 72m2, the comfortable apartment exceeds the minimum requirement for one bedroom apartments in Ireland by 60%, its irregular plan opening up to the strangely distant metropolis forty floors beneath. Neither sky nor ground are visible from inside, the city looms above and disappears from view below.

Residences are raised above 19 floors of parking – an unavoidable reality of 1960s America – and as the first major development in a declining industrial area, lifting the residential blocks may have given some relief from the smog and dust below. This conversely embodied a kind of “anti-urban” philosophy where multiple levels of parking dominate and “eyes on the street” are non-existent. The “city within a city” mantra perhaps becomes an island within a city. Despite its achievements, Marina City’s anti-pedestrian urban edge with moat-like level changes and large car ramps, removes any sort of meaningful presence at street level to non residents.

Although the area now bustles with restaurants, bars and apartments, it is far from atypical residential neighbourhood. Flanked on three sides by streets that have more in common with the M50 than most urban environments; six lanes of constant traffic, window rattling subwoofers and illegal drag racing and are common late night nuisances.

Connection between residents can also feel strangely isolating. Elevators are not conducive to forming relationships and the curving plan allows for interaction between neighbouring balconies but doesn't encourage either. These large balconies feel like an interpretation of the traditional American porch lifted into the sky, shaded relief from the summer sun, or sheltered hideout to watch colossal lightning storms roll over the great plains and crash into Lake Michigan. They also allow you to engage in the longstanding American tradition of watching your neighbours from the porch.

Looking across to the adjacent tower, presumably people are enjoying their balconies, but they are lost against the infrastructural scale of the complex. Voices drift across, a party far above, arguing below. If you look closely enough they start to emerge. A TV flickers on, they're watching Friends, “Brian” from the local bar waves over as he's brushing his teeth on his balcony, a couple shut their blinds after drinking a bottle of wine on the balcony. Like L.B Jeffries looking out his rear window, I wonder if I am the only one piecing these disparate stories together. The feeling is one of shared isolation rather than community, alone together high above the chaotic streets below.

That is not to say there is no community here. A thriving residents group exists if you decide to partake. Movie nights occur weekly, taking place on the roof deck in the summer months. Art talks, game nights and seasonal parties regularly fill the shared amenity space.

Irish perceptions of community are more parochial; passing neighbours at the front door, greeting the postman. While traditional domestic formations may be useful facilitators for chance encounters, it is naive to imagine that communities require a specific type of urban form to propagate. Communities are formed by longevity and security. Apartments here are privately owned or leased long term, but beyond that, residents are fiercely proud of their iconic modernist home. The ambition of drawing people back to the urban center was achieved by creating liveable homes. Many residents have been here for decades, some from its very inception.

Despite the abundance of new construction in Ireland, the race to the bottom of minimum standards and the prevalence of build-to-rent schemes prevents apartment living being seen as a viable long term option. The corporatisation of housing provides neither the long term security nor exemplary housing needed to form community or societal change.

Similar to the Irish housing crisis, urban dereliction in Chicago was an immediate problem that needed a swift response. The architects and – crucially – an ambitious funder, understood that an exemplary project was needed to shift societal attitudes, not a short term band-aid. Marina City stands as a testament that radical solutions can significantly alter public opinion and trajectory of an urban area. This kind of thinking is urgently required, and if we must look up and abroad for solutions, then let us ponder on the porches of Marina City.

In this article Dónal O’Cionnfhaolaidh reflects on high rise living, community, and the legacy of an architectural icon after four years of living in America's most ambitious residential project.

ReadOn visiting the Villa Tugendhat in Brno, one might be struck by a couple of things. First, on entering the building, the air in the hallway is stale, a result of the inoperative original air-conditioning system. Secondly, the planning of the basement service floor is surprisingly chaotic. These two observations suggested to me a narrative about modernism’s dependence on technology and about Mies’ attitude to that technology – and the situation of architecture in general in relation to technical measures.

Mies worked in more than one register when designing the villa. The top floor, with the entrance hall and bedrooms, is fairly straightforward: lucid and rational. The floor below, what I suppose in German could be called the Beletage, has a flowing and expressive plan comparable to his single-storey Barcelona pavilion. Like the Barcelona pavilion, it has a representative purpose: it contains spaces for entertaining, constructed with fine materials which convey the wealth of the inhabitants. The basement below is half-buried in the hillside and contains mostly service spaces. The layout of the basement feels strikingly unresolved in comparison to the other floors.

The plan of the basement is not often published. It contains, among other things, a boiler room, a laundry room, the room-like processing chambers of the air conditioning system, a photographic darkroom for Mr Tugendhat, and a “moth chamber” where fur coats were stored. These functions are arranged in a way that is partly determined by the layout of the floor above. For example, the dumb-waiter is at the end of a narrow corridor around which a contorted storage room is wrapped. It’s as if the occupants of the basement scurry around this warren of spaces to pick up the loose ends of the freely-planned floor above. There is no functionalist virtue on display here. Indeed, the tiled and napthalene-impregnated moth chamber, accessed through the darkroom, is at the end of a chain of five rooms. It gives a claustrophobic impression tainted by the idea of moths as vermin, and of a cruel method of industrial extermination. The technology of circa 1930 is reflected in the primitive air conditioning system: a piece of apparatus firmly fixed in history, but one in service of the apparently timeless perfection of the upper floors.

It seems that Mies did not consider the basement floor to be part of his architectural expression. He didn’t optimize it. The terse open-plan geometry of the main living spaces reflects not just freedom of movement for the inhabitants, but Mies’s freedom of design. It is simple in comparison to the complex technicalities of actually keeping the house running.

The closest thing the villa has to a centrepiece is the orange onyx wall, non-load-bearing and composed of five slabs. While one could interpret this as a pure display of luxury, it is also an object of contemplation (or at least a talking point). The Tugendhat family were cultured as well as wealthy, and I want to attribute to them some kind of elevated curiosity about this object. What can we recover, in the way of intellectual depth, from reflecting on the onyx slabs? A suitable source might be the French philosopher Roger Caillois, who, in his book The Writing of Stones [1], discerned in geological patterns “some ancient, diffused magnetism; a call from the center of things; a dim, almost lost memory, or perhaps a presentiment, pointless in so puny a being, of a universal syntax.” In relation to the Villa Tugendhat, where the setting sun causes the backlit onyx to glow translucently, Caillois’s words evoke an understanding beyond the codes of architectural modernity. Mies’s obsessive refinement of his constructional poetics certainly has something to do with striving for a universal syntax, and the connotations of cosmic grandeur must have been intended as well, but the awkward, “puny” insignificance of humanity, in contrast, doesn’t seem to find a direct expression in his design. A stone is an indifferent thing.

Caillois wrote “Life appears: a complex dampness, destined to an intricate future and charged with secret virtues, capable of challenge and creation. A kind of precarious slime, of surface mildew, in which a ferment is already working. A turbulent, spasmodic sap, a presage and expectation of a new way of being, breaking with mineral perpetuity and boldly exchanging it for the doubtful privilege of being able to tremble, decay, and multiply.” [2] Although Caillois did not have architecture in mind, these vivid words evoke, in contrast to the timelessness of the onyx wall, the more fragile reality of the Villa Tugendhat, a reality of uncertainty that undermines Mies’s confident form-making. At the most basic level, the presence of humans means the presence of water vapour and all manner of microbial impurities. These are perennial problems for the architect: problems of climate control and hygiene. The handling of the response to them (the concealed inventions and intricacies of the air conditioning equipment) is arguably a truer token of humanity than the stony perfection of polished onyx panels.

The flight of the Tugendhat family from Brno in 1938 in the face of the impending Nazi occupation is emblematic of the precariousness of civilization and of an industrial society gone astray. The grand formal spaces of the villa have an appropriately monumental character, as Mies intended, but the technical floor tells another story of historical contingency, unresolved difficulties, and of all the problems we try to sweep under the carpet.

Editor's Note: An exhibition on the architecture of the Villa Tugendhat will run in the Irish Architectural Archive from January to March 2026.

Throughout its evolution, architecture has been required to engage both with imperfect technologies and the contingencies of life. This is clearly evidenced in Mies Van der Rohe’s Villa Tugendhat. The villa has a public face of rare perfection, but other aspects make one wonder about the architect’s ethical stance in relation to functionalism and humanity.

ReadYet in Ireland today, the built environment is too often defined by crisis; housing shortages, vulture funds, stalled planning, delayed public infrastructure, and sprawling suburbs with inadequate public transport. Across these challenges, one pattern is consistent - people’s needs have been systematically sidelined in favour of economics. This raises two critical questions; how did people become invisible in planning, and how has this eroded public trust?

To contextualise this argument through a recent controversy, the proposed redevelopment of Sheriff Street has been presented as a scheme designed to ‘regenerate the area’ and tackle underdevelopment. Yet, Rainbow Park, a green space in the heart of Sheriff Street, remains untouched despite long-standing calls from residents to transform it into a vibrant hub. According to Mark Fay, chairperson of the North Wall Community Association, residents were also blindsided by the announcement, revealing how little meaningful consultation took place.

Urban theorist David Harvey has argued that regeneration often masks gentrification, where the well-being of current residents is sacrificed to increase property values. The office blocks and luxury apartments planned for Sheriff Street are designed for people largely ‘unindigenous’ to the neighbourhood, while those already living there risk cultural erasure. This is part of a larger pattern of gentrification dressed as renewal, sanitising inequality rather than addressing it.

So how might architectural practice move away from this cycle and begin to approach the built environment in a genuinely democratic way?

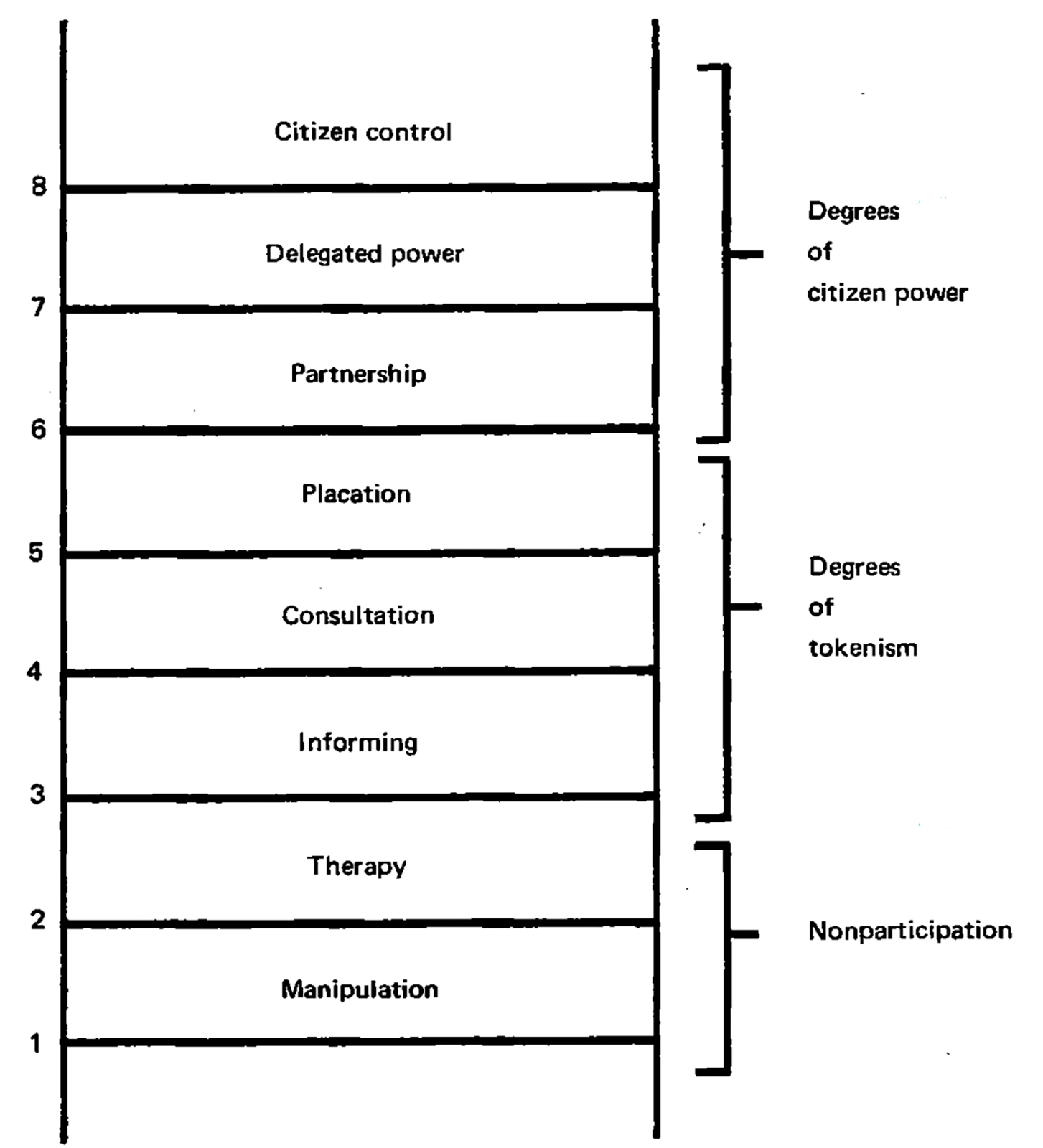

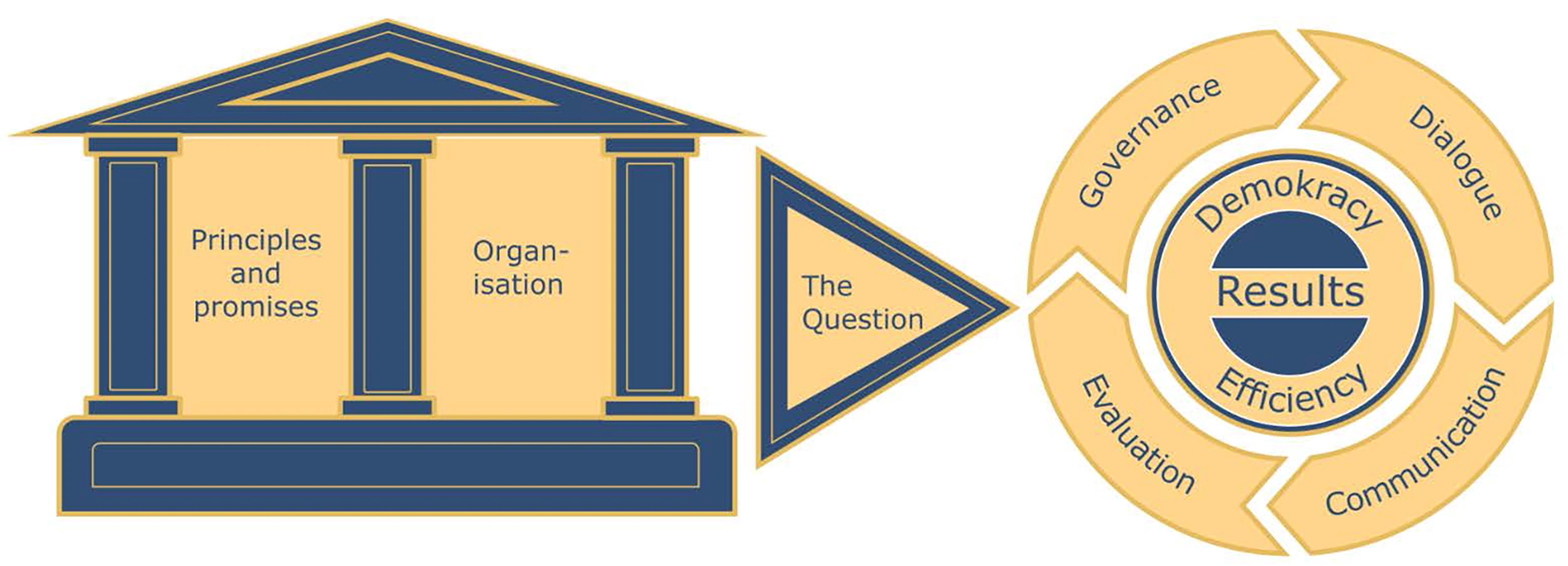

Public consultation has been offered as a solution, but in practice often amounts to little more than a box-ticking exercise. Public forums tend to come late in the design process, when decisions have already been made, leaving residents feeling duped. In order to truly facilitate democratic design, communities must be involved from the very beginning, when needs and opportunities are first identified. This must then be followed by genuine co-authorship, where residents have a real stake in shaping outcomes. And even this is not enough if architects and planners fail to develop empathy for the people behind the feedback.

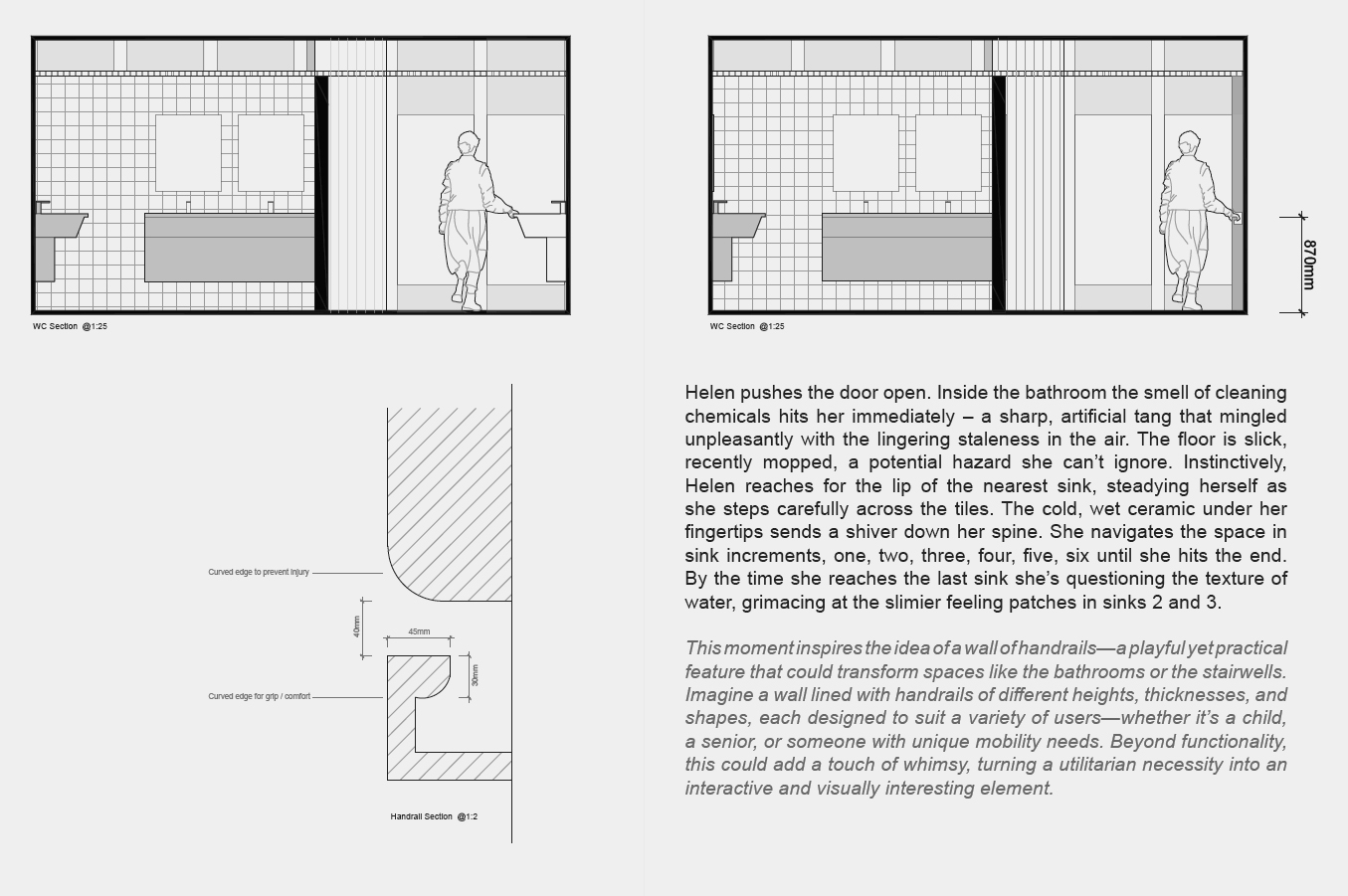

This is where the act of ‘writing people back into design’ becomes important. ‘Fictional Narrative Writing’ is a methodology that I have developed which merges writing, storytelling, and narrative empathy, helping designers to integrate people and identities into their work. This involves creating characters and scenarios drawn from what is learned in the early stages of design development, and then designing through their eyes. Imagine Susan, aged forty-six, recovering from a hip replacement, needing to move comfortably through a building or public space. Or Steven, aged sixteen, with little money and nowhere safe to gather with friends. How might a street, square, or public building serve both of them? By imagining these lived experiences, architects are forced to consider how spaces perform for different people, ensuring that those consulted at the start are not only listened to, but remain present and visible in every stage of design.

By embedding empathy in practice, designers begin to understand diverse people’s needs, desires, and vulnerabilities, while the public sees themselves reflected in the design process. This mutual recognition rebuilds trust, transforming the built environment from a top-down imposition into a shared project of social life.

Above all, this methodology requires us to acknowledge that architecture is never neutral. Every design decision is a social, and therefore political, decision. This is not a plea for grand gestures, or expensive experiments. Often, small interventions can transform how a space is experienced. A family-friendly bathroom that gives independence to children. A sheltered bench that restores dignity to those waiting for the bus. Free, accessible indoor spaces that provide refuge to teenagers who have nowhere else to go. Inclusive facilities that allow people to exist without fear of scrutiny. These are not luxuries. They are the basics of a society that values its citizens.

Ireland is at a crossroads. The choices we make now will determine whether the built environment continues to alienate, or whether it begins to reconnect people, and foster a sense of community. We can persist with Tetris-block developments dictated by developer economics, or we can restore architecture’s social purpose. The shift will not come overnight, nor will it come through tokenistic frameworks. It requires a change of mindset, to see people not as passive recipients but as co-authors of the places they inhabit. It requires putting dignity and a sense of belonging on equal terms with cost and efficiency. It required introducing empathy as a design tool.

If we succeed, trust can be rebuilt. Our cities and towns can become places of pride rather than disillusionment, and the phrase ‘built environment’ can return to its true meaning: the collective spaces where people live - and live well.

It is time to write people, community, and democracy back into Ireland’s built environment.

The built environment is defined by Oxford Languages as ‘man-made structures, features, and facilities viewed collectively as an environment in which people live and work’. Looking beyond the sexism, naïve assumptions of inclusivity, and the capitalist emphasis on perpetual labour engrained in this definition, two words stand out: ‘people’ and ‘live’. I highlight these words as a reminder of the purpose of the built environment, and for whom it exists. The built environment should be a proactive space that empowers people to live a comfortable, functional, and democratic life.

ReadThe Planning and Development Bill 2023 is currently making its way through the Oireachtas, with planning policy reforms focused on ‘efficiency’ to achieve growth. These reforms intend to streamline planning processes and accelerate decision-making. The consequence of a market-led approach to local planning is a reduction in the scope of citizens’ democratic right to have a say in the future of their towns and cities. The future system risks further limiting local debate over local change, while the current system fails to sufficiently harness local knowledge and invaluable stories of place. There is an alternative approach. In Ireland, there is an embodied culture of storytelling that naturally lends itself to a form of public engagement that creates space for dialogue.