Already functioning as a successful reuse of an old industrial infrastructure without any intentional architectural intervention, the Royal and the Grand Canals are likely our largest, and certainly longest, public spaces in the city. From the moment the sun emerges in spring, to late autumn, they bustle with activity, hosting commutes, walks, runs, and late-night gatherings. These truly vital spaces were gifted to the city by the cyclical nature of industrial change. Decommissioned, they have persisted throughout the success and decline of Dublin, fostering public social space which is increasingly rare within the stoic red-brick city centre. Our canals offer roots from which civic and cultural spaces may grow.

A reflection from John Banville’s Dublin memoir, Time Pieces, illustrates the canals’ enduring appeal:

“… by the canal at Lower Mount Street Bridge and watched a heron hunting there beside the lock . .. I told her I loved her, but she closed her eyes and smiled, with her lips pressed shut.”[1]

Dubliners display a love for their city on these banks every summer, and yet it goes on unrequited. Public spaces adjacent to the Grand Canal such as Portobello Square and Wilton Park are being eroded by speculative demand, despite their evident popularity in a city thirsty for space. Portobello Square is a rare open public square directly abutting the canal, so intensely popular at times that the authorities see no other crowd control option but to physically impede the public from occupying it. In 2021, Portobello Square was boarded up and temporarily privatised in return for an investment in its redevelopment.[2] This was a convenient alignment of interests, as the space had also been fenced off the previous year to prevent anti-social activity.

The Grand Canal’s banks often do not inspire hope in the here and now, instead becoming a discomforting reflection of our town and country. The most recent fencing off of the canal to prevent its occupation by unhoused asylum seekers [3] proved unpopular, not solely for its inhumanity, but also its cost. Hope, however, lies within this provocation; the moment of inflection should be seized to offer a new scale of social and cultural infrastructure to the city. The canals are crying out for rejuvenation through a top-down shift in thinking, to irrigate the city with public cultural spaces, foster more pace for unexpected encounters and more feed for the friction and forum that cities are ultimately about. Another greenway won’t activate the canals’ multitudinous potential to invigorate their dense urban surroundings.

Plans released by Waterways Ireland at the beginning of this year set out to enhance public seating, increase accessibility, and combine two existing narrow pathways to form one wider path.[4] Unfortunately, these proposals fall short of the ambition these urban spaces so desperately need. Combining pathways may optimise the space as a liminal venue of commute, yet may equally alienate those who use the bank as a space for slower, un-programmed occupation. Addressing the challenge of these banks’ inability to support year-round activity within their current footprint seems quite the daunting task.

The canals would benefit from receiving intentional interventions beyond their immediate banks to amplify their use. Where possible, the tarmac roadways lining the canal banks should be reappropriated in service of the canal corridor, providing and connecting into adjacent cultural spaces. In King’s Cross in London, a sculpted mediation of the streetscape down to meet the water’s edge becomes seating for an outdoor cinema during summers[5], and in Paris, new businesses are opening in alcoves along the Seine, unlocked by the riverside’s pedestrianisation.

One thing has become abundantly clear, engagement in this issue should not be the sole task of Waterways Ireland. At minimum, council authorities should engage with W.I. to support their common ground. As it stands, similar to the redevelopment of Portobello Square, the current W.I. proposal for the Grand Canal’s banks involves a public private partnership, with IPUT Real Estate part-funding the works to the canal banks.[6] Unfortunately, investment of substantive urban change always seems to lie beyond the remit of the local authority, Dublin City Council.

When the building of the Grand Canal was commenced by the Board of Inland Navigation almost 270 years ago, it was government founded, funded and led.[7] Dublin City was building much of what we now see as its most definitive urban fabric, public and private, at a time when architectural neo-classicism proliferated with bold metropolitan might. The Rotunda, Grattan Bridge, Parnell Square, and Gandon’s Customs House, are just some of the iconic city elements built in this time. Perhaps in our government’s present moment of liquid economic abundance, we should aspire to a new era of bold urban thinking; a new scale in what we demand from our city; and, ultimately, in what we propose that our city becomes. The canals are a good place to start. Their waterway function now secondary, the city should lean in, commit to the development of this deeply urban space, and allow the future of the canals to define Dublin anew.

One Good Idea is supported by the Arts Council through the Arts Grant Funding Award 2025.

[1] J. Banville, Time Pieces: A Dublin Memoir, Dublin, Hachette Books Ireland,2016.

[2] L. Neylon, “Developer Might Help Fund Revamp of Portobello Square in Exchange for Using It for Storage”, in Dublin Inquirer, Dublin, 22 December 2021. Available at: https://dublininquirer.com/2021/12/22/developer-might-help-fund-revamp-of-portobello-square-in-exchange-for-using-it-for-storage/[accessed 09 January 2025].

[3] K. Sharkey, “Dublin asylum seekers: ‘Ring of steel’ along Grand Canal”, in BBC, 2024. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c72pplgjdkjo,[accessed 09 January 2025].

[4] “Waterways Ireland and IPUT Real Estate to Transform Dublin’s Grand Canal at Wilton Terrace”, in Waterways Ireland,2025. Available at: https://www.waterwaysireland.org/news/waterways-ireland-and-iput-partner-to-transform-dublin-s-grand-canal-at-wilton-terrace,[accessed 26 January 2025].

[5] S. Barker, “A Free Canalside Film Festival Has Landed In King’s Cross”, in Secret London, 2024. Available at: https://secretldn.com/screen-on-the-canal/,[accessed 26 January 2025].

[6] “Waterways Ireland and IPUT Real Estate to Transform Dublin’s Grand Canal at Wilton Terrace”, in Waterways Ireland, 2025, Available at:https://www.waterwaysireland.org/news/waterways-ireland-and-iput-partner-to-transform-dublin-s-grand-canal-at-wilton-terrace,[accessed 26 January 2025].

[7] H. Phillips, “Early History of the Grand Canal”, in Dublin Historical Record, vol. Vol.1, 1939, 108–119. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30084149[accessed 9 January 2025].

‘I think of colour as a thing, not as an abstraction, Motherwell said, I do not draw shapes and then colour them blue; I take a piece of blue, a large extension of blue and cut out, so to speak, from the extension of blue as much as I want. Color is a thing for me, and not a symbol for something else, say, the sky: though associations are unavoidable’ 1

Robert Motherwell was an accomplished Abstract Expressionist painter, working in New York in the mid-1900s. As a loosely affiliated group, the Abstract Expressionists were dealing with the picture plane as a surface to be challenged; the illusion of forced perspective and the classical tradition were anathema. This was New York at the dawning of the atomic age: charged shallow surfaces, devoid of overt subject formed the painterly agenda. The dominance of the centre and dialogue with the periphery were European preoccupations – here, a broader assertion across the entire canvas prevailed. Motherwell did not receive the acclaim of his peers De Kooning and Newman during his lifetime, but had the innate ability to cogently formulate a theoretical position for the movement. He articulated colour as raw material, physical, devoid of association and baggage. He could extricate object from subject in a way that furthered his practice.

The contested ground between object and subject has preoccupied philosophers and artists for generations. A gap between the ‘thing-in-itself’ and our knowledge of it was articulated by the eighteenth-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant. He posited that things are sidelined to ‘discrete objects of thought’ [2]. ‘Kant’s gap’ – as it was later coined – was a flaw in his early critique of reason. However, this instinct feels intuitively like the intellectual bedrock for subsequent discourse. Philip Guston has written about this gap, and how naming is a form of masking or concealing [3]. Tacita Dean talks about naming as a consequence or response to the object [4].

Architecture has a challenging relationship with object and subject, or, in other words, building and program. Yet there is perhaps a lesson from Motherwell for contemporary urbanity. In an age of climate emergency and urban dereliction, the embedded carbon within the built artefacts of our towns and cities requires us to look harder at what once was a department store, bank, or shop. These are simply labels applied to an assemblage of materials, gathering and framing a set of singular or collected volumes. An objective analysis of the inherent characteristics (material, spatial, structural) of these buildings would establish a number of potential lives beyond their current application. Georges Perec deployed this objectivity in the way he engaged with and wrote about the city around him. He unpacked the quotidian through straightforward observation. Such clear vision is difficult with the noise of subjectivity and latent associations often clouding our judgement.

In this way, the age of the defined architectural typology feels outmoded. Rossi would perhaps have retorted that it is typological rigidity that gives structure to cities, and aligns them with a collective memory. Although the gestalt assemblage of pictorial city monuments still holds true, I don’t believe that the contemporary city performs in this manner anymore. Urban interiors no longer necessarily hold that which they project. And if they do – in the case of banking halls for example – their inherent characteristics have typically been buried beneath layers of intervention. Our urban realm has been so distorted by late capitalist consumer culture – and the digitisation of the commons – that the assertive associative force of typology has waned. We can and must reach for a deeper morphology within the cities and towns which we inhabit.

I’m leaning on artists again for the heavy intellectual lifting, because their penetrating gaze and ability to look hard without the burden of function can be instructive in reappraising our built environment. Joseph Beuys would talk of ‘substance’, a sense beyond the visual or retinal that is more bodily and sensorial. He suggests that the eye lazily reverts to the function of a camera unless the other senses are engaged in communion with it. This intensified engagement with our urban artefacts is perhaps a good place to start. The artist David Bomberg, one of the leading post-World War II teachers at the London Borough Polytechnic – his students included Auerbach, Kossoff and Metzger – emphasised the study of matter and actuality. The tangibility of spaces grasped and held by gravity.

This approach was the basis of the ‘Building Societies’ project Sarah Carroll and I (now practising as TRESTLE) proposed as part of the IAF and the Housing Agency’s Housing Unlocked exhibition (2022-2023). Our proposal responded to Bank of Ireland’s decision in March 2021 to close 103 regional branches, fundamentally altering the physical, social, and economic landscape of Irish towns. As these unique bank buildings were parcelled up for sale, Sarah and I started to consider their legacy and latent potential. Our idea reacts to the supply crisis within the housing market and reimagines the value and currency of these bank buildings as urban vessels within which housing opportunities can be explored; firstly, for homes above the bank, and secondly, through opening up the generous banking hall as a covered freespace that unlocks backland housing sites and spaces for wild nature, play, and urban growing.

If we momentarily step back, though, from Ireland to a geographically broader civic context, there is an inherent underlying shape to all European settlements. Although the Romans didn’t invade Ireland, the inheritance of their militarised urban planning strategy on the island’s urban grain is still apparent. This loose morphology still holds true across western Europe, and therefore a crisis of urbanity is emerging beyond these shores alone. But Ireland is blessed with another setting down of culture by her people. Original Irish names such as sliabh (hill), and abhainn (river) bind landscape features and oral culture, fostering a lore centred around place: logainmneacha. This speaks to an even deeper registration of environment: deep time. Deep time is the patient accumulation and layering over millennia to form our underlying surroundings, something we think about too little in the Anthropocene.

The insatiable process of capitalist production and consumption has stifled our ability to appraise slowly, to think thoughtfully. This is coupled with procurement challenges, a conservative and entrenched building sector, and planning hurdles. The urban typologies which once provided the physical and programmatic structure of our towns and cities have in many cases become vacant or stripped of their original meaning. This presents both an opportunity and a challenge. In the dual context of the climate and housing emergencies, there is an ethical imperative to apply our gaze more forcefully towards the potential within the existing built fabric. Considering the collective assemblage of volumes and artefacts within our towns and cities more abstractly and substantially could assist us in discovering their latent potential and unlocking the next phase of their civic development.

In assessing how to reuse the built fabric and harness the latent potential of our towns and cities, architects have much to learn from artists about disconnecting object and subject, argues Tom Cookson.

Read

If a river could speak, what would it say? What if rivers, streams, and other waterbodies were recognised not as inanimate resources, but as living entities with their own agency? Such recognition would require a profound shift in how we regard, design, and inhabit landscapes shaped by water.

Across Ireland, rivers have shaped our cities, towns, and rural areas. They are woven into cultural identity, sustaining industrial, agricultural, and civic life. Early communities lived by the logic of water – organising around its seasonal rhythms for trade, farming, and gathering. This reciprocal relationship enabled social and economic stability. Over time, however, industrialisation and urban expansion reoriented human life away from water. Rivers were channelled into systems of economy, energy, and urban growth. As Sir William Wilde observed in his appraisal of the River Boyne and Blackwater, ‘the inhabitants of Navan, like those of most Irish towns through which a river runs, have turned their backs upon the stream’ [1]. This disconnection remains embedded in cultural perception and physical planning.

Today, climate volatility and ecological degradation demand a re-examination of our societal relationship to water. Riverscapes are increasingly fragile; their loss would severely undermine biodiversity and ecosystem resilience. The contemporary challenge lies in rediscovering the ecological intelligence that rivers possess and reinstating modes of coexistence that value water as a living system [2].

Rivers are dynamic environments shaped by erosion, flooding, and time – forces that, when left undisturbed, sustain balance. But industrial pollution, agricultural intensification, and mismanaged urban runoff have disrupted these processes. Such practices have wounded river ecologies and diminished their capacity for self-regulation. Nevertheless, as Robert MacFarlane’s explorations in his book Is a River Alive demonstrate, ‘hope is the thing with rivers’ [3]. Given space and care, river systems can recover rapidly. This possibility underscores the importance of stewardship over exploitation. Restoration begins with recognising the river as a partner in regeneration rather than a passive resource.

Rebalancing human–river relations requires the integration of ecological science, cultural practice, and participatory engagement. A regenerative and reciprocal approach would prioritise both ecological function and social value. Artistic practice can serve as a mediating tool, helping communities to perceive and interpret the agency of water. The act of ‘deep listening’ – through soundscape studies and field recordings – offers a method of reconnecting with river environments and can re-sensitise us to the voices of the non-human world.

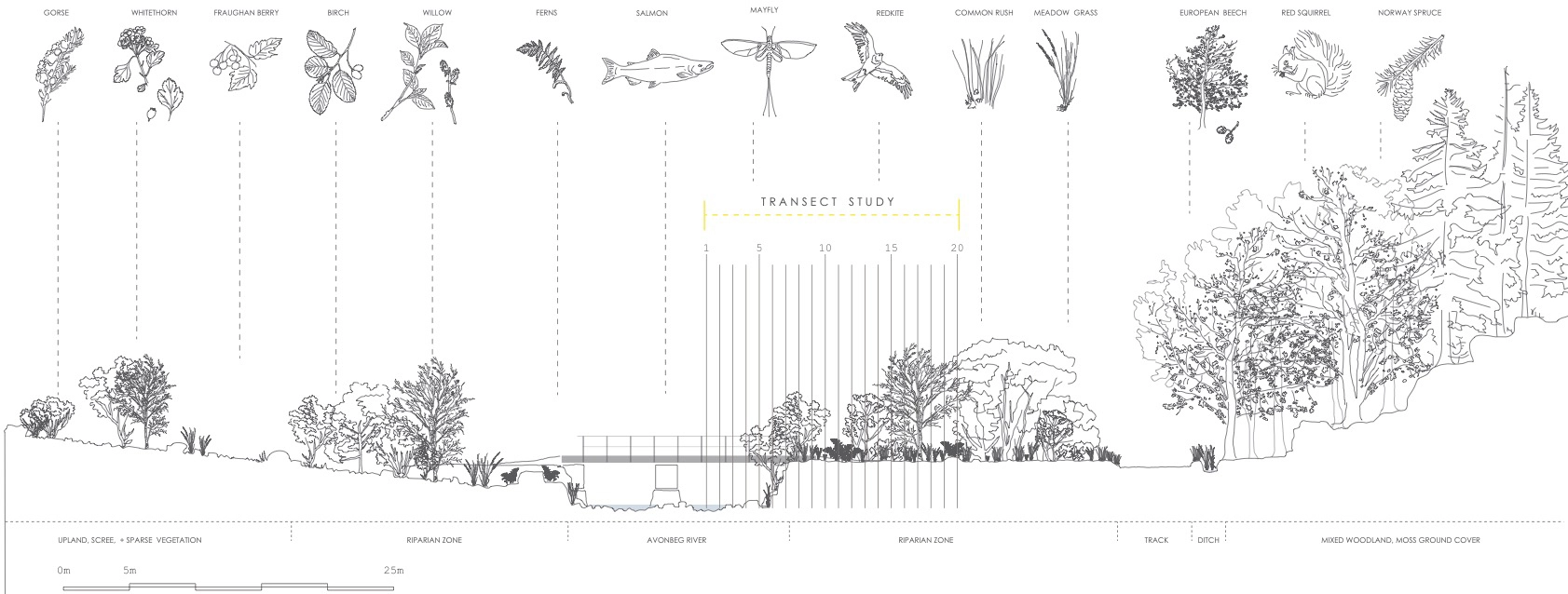

Sound is an indicator of ecological vitality. The sonic landscape of a healthy river – birds, insects, flowing water, and wind – reflects biodiversity. There is as much to learn from silence as from sound. Using extended field recording tools such as hydrophones, contact microphones, and acoustic sensors, we can listen beneath the surface, to trees, soil, and water itself. Ecologists increasingly employ soundscape spectrogram analysis to assess habitat quality and species distribution. Publicly accessible app identifiers, such as Merlin or Biodiversity Data Capture, enable citizens to participate in environmental monitoring through listening. Thus, sound becomes both a scientific and a democratic mode of attention. These slow-observation techniques help us grasp both the strength and vulnerability of these ecosystems, enabling us to take the right actions in the right places to support the river [4].

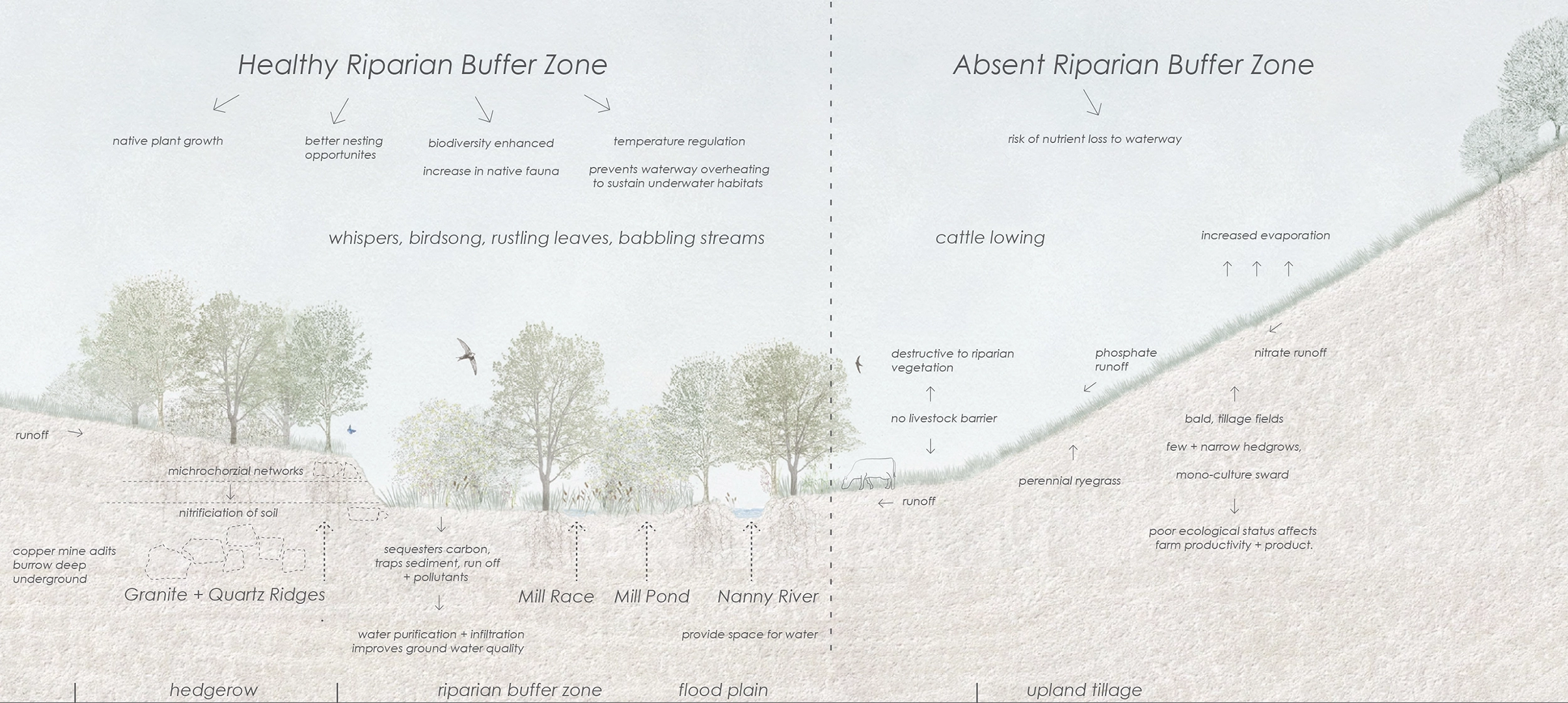

The ecological health of rivers is intrinsically linked to riparian buffer zones: the vegetated margins between land and water. These areas function as natural biofilters, trapping sedimentation, absorbing pollutants, and stabilising banks while providing shelter, habitat, and food for countless species. Despite their importance, many have been drained or grazed to maximise land use. Nutrient loss, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus runoff, contributes to eutrophication, whereby water becomes overly enriched, leading to a dense growth of algae and aquatic plants. These blooms reduce oxygen levels, and oxygen is required to support fish and other aquatic life [5]. Controversially, the EU Nitrates Directive has permitted Ireland to continue to exceed the standard manure limit of 170 kg nitrogen per hectare, albeit with stricter requirements to protect water quality [6].

In the Boyne Valley catchment, where agriculture is the main significant pressure, only one river is achieving high ecological status and 51% of waterbodies are at risk of not meeting their environmental objectives [7]. The River Boyne is a designated SAC and SPA, however, riparian habitats are fragmented, degraded, or absent with few native woodlands remaining. Inland Fisheries Ireland have warned that Atlantic salmon stocks have fallen to some of the lowest levels on record and important river birds such as the lapwing and sand martin are ‘of conservation concern’ [8]. The decline of these species indicates a broader threat to the entire river system. In addition, the Department of Housing has proposed to classify certain stretches of the Boyne and Blackwater as ‘heavily modified water bodies’, a move which could essentially relegate our legal obligations to restore them [9].

The restoration of riparian buffers is central to water quality improvement and climate adaptation. Properly managed buffers are essential for intercepting and reducing diffuse pollution before it reaches waterbodies [10]. Beyond their ecological function as green corridors, riparian buffers also support human wellbeing, offering spaces for play, recreation, education, and multi-sensory restoration. Walking along a river, listening to it, and observing its cycles of change can help regulate emotions, reduce stress, and elevate mood. Three recent EPA research programme studies (2014–2022) – GPI Health, NEAR Health, and EcoHealth – found measurable physical, mental, and social health benefits associated with access to green and blue spaces[11]. In urban contexts, these buffers can reconnect communities with waterways that have long been inaccessible or overlooked. Such holistic relationships with nature can foster healthier communities and help futureproof society against environmental uncertainty.

Rezoning riparian land as cultural and ecological corridors offers a framework for integrating environmental resilience with public amenity. Public parks, heritage landscapes, and post-industrial sites can host new programmes that coexist with water while balancing protection, access, and conservation. Instead of resisting flooding through hard engineering, adaptive design can accommodate seasonal pressures through wetlands, soft embankments, and absorbent landscapes.

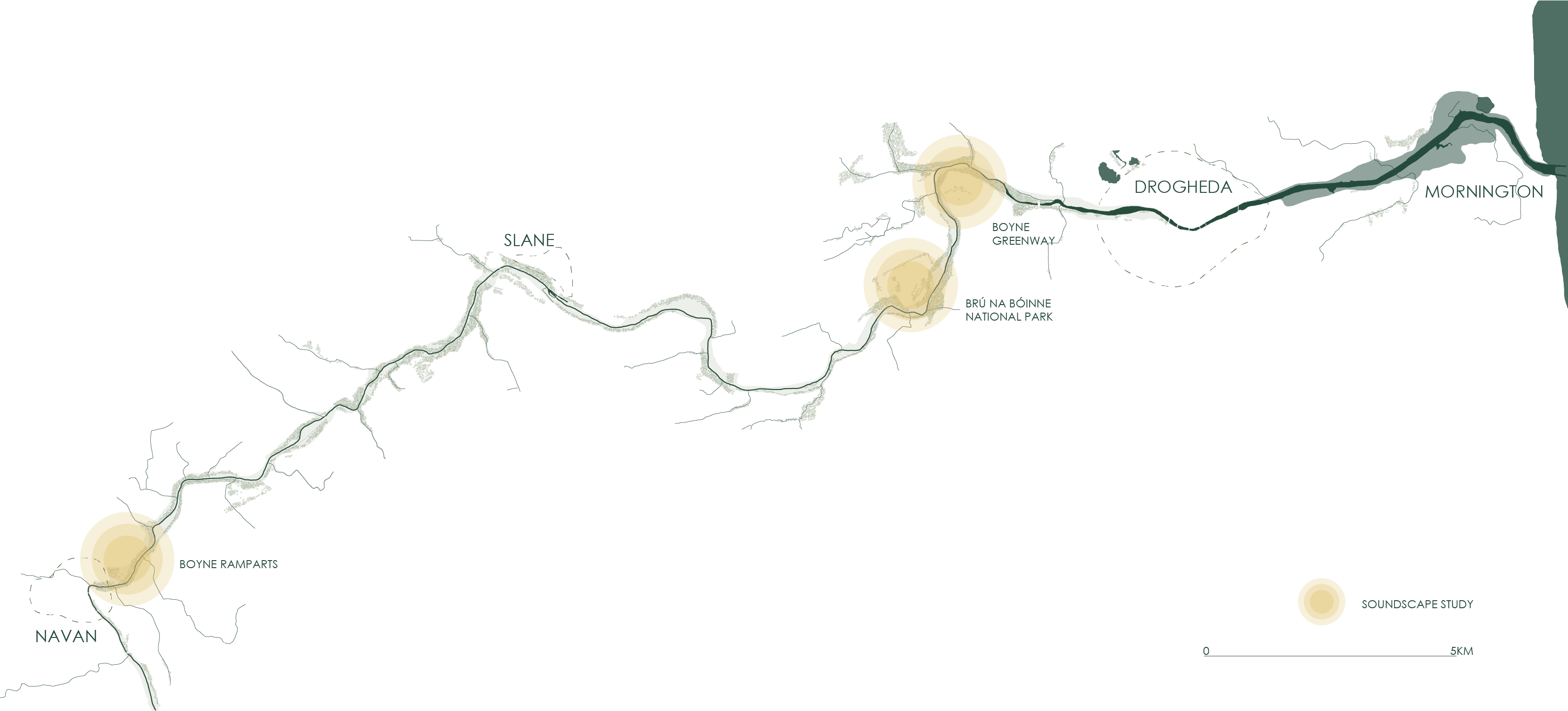

The River Boyne provides a valuable case study. Along its course, several significant public sites – Oldbridge, Newgrange, Slane, Trim Castle, and Brú na Bóinne [12] – offer opportunities to lead this change. These areas, already rich in heritage and ecological value, could restore riparian zones and improve biodiversity while enhancing public space for human and non-human amenity. Similarly, the proposed Boyne Greenway between Navan and the Mary McAleese Boyne Valley Bridge could become a model of designing with the river as a living stakeholder rather than as an element of infrastructure.

Building solutions from the ground up is vital. Local industries, landowners, and government bodies are accustomed to the old extractive land use practices. Schemes such as IRD Duhallow’s LIFE project [13] or the Inishowen Rivers Trust’s ‘Cribz’ [14] managed to bring relevant stakeholders together to highlight their role in their local river's conservation. Both projects found that community-based engagement promoted environmental stewardship and action in their localities. Artistic and cultural interventions can complement scientific approaches by cultivating empathy and imagination. Place-based workshops that integrate art, ecology, and citizen science invite participants to engage with rivers experientially, through listening, recording, and collective observation [15]. Such participatory methods expand environmental knowledge beyond data collection to include sensory, emotional, and ethical dimensions. They encourage us to slowdown, listen, and experience the river directly. These activities foster empathy and understanding, reconnecting participants with the landscape.

Creativity can help us reimagine our systems for climate adaptation. Partnerships between artists, scientists, local authorities, and environmental groups can strengthen collective capacity for change. Local arts organisations provide platforms for dialogue and dissemination, helping to transform awareness into action. Interdisciplinary collaboration bridges the gap between ecological science and public perception, and can generate community-driven models of stewardship.

Led by Scape Architects, the Chattahoochee RiverLands Greenway Study in Atlanta, Georgia, proposes a linear network of greenways, blueways, and parks, shaped through local interviews, immersive experiences, participatory design charrettes, and public forums [16]. Following a similar approach, Take Me To the River – a collaborative initiative between the Solstice Arts Centre and Cineál Research & Design – has been cultivating connections with the local council, water authorities, river-trust networks, and communities. Through creative, site-based public workshops and exploratory mapping exercises, the project is developing a layered understanding of the river catchments of County Meath [17].

Ireland’s Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity Loss has called for the recognition of rights of nature in the Constitution, to provide a stronger legal framework as we face accelerating species decline and biodiversity loss [18]. Assigning the concept of ‘riverhood’ to waterways acknowledges their intrinsic right to exist, flow, and regenerate, independently of human interests.

Reimagining rivers as sentient entities invites both ethical and practical transformation. It challenges dominant paradigms of extraction and human control and instead proposes relationships grounded in indigenous and ecological understandings of reciprocity. In Celtic mythology, the goddess Bóinn’s spirit became the River Boyne, giving it associations with poetry, fertility, and wisdom.

Restoring riparian buffers and ecological corridors can enable rivers to function as autonomous living systems within interconnected landscapes. Healthy rivers create natural pathways for wildlife, filter our water, and stabilise our climate. With ecological renewal, interdisciplinary collaboration, and creative engagement, they canal so provide us with spaces for reflection, imagination, and belonging.

If a river could speak, it might remind us that every act of care or neglect upstream reverberates downstream and that stewardship begins with attention. To listen to rivers is to acknowledge our shared dependence within a living system.

In this article – timely, in light of recent flood events – Phoebe Brady and Sarah Doheny argue that integrating environmental resilience with public amenity and treating rivers as living stakeholders, rather than as elements of infrastructure, is essential if we are to ensure the survival of our watercourses and our ecology.

Read

Three seemingly unrelated stories caught my eye in the news in recent months. In the Dublin suburb of Dundrum, residents spoke out in opposition to a proposal to build an “aerial delivery hub” in the centre of the town.[1] A meeting organised by local politicians was attended by the chief executive of the drone company, but this wasn’t enough to convince the citizens of Dundrum that the new hub was a good idea.

A few weeks earlier, Irish billionaire businessman Dermot Desmond was reported as having described the long-awaited Metrolink project as obsolete and “a monument to history”.[2] He argued that autonomous vehicles operated by artificial intelligence would make the rail line redundant, would cut the number of vehicles on the road dramatically, and eliminate congestion. His argument was dismissed by transport experts and citizens alike.

More recently, in the annual scramble for housing, students in Galway spoke in despair about the lack of available accommodation, noting that there are currently over 1,000 properties listed on Airbnb for Galway, while there are only 111 properties to rent on Daft.ie (in fact, the figure maybe below seventy).[3]

What these three stories have in common is that they are all underpinned by technologies which aim to minimise social interaction within our cities, based not on a desire to provide a service to society (whatever their proponents might claim), but to extract maximum profit by eliminating the cost of people doing real work.

Canadian writer Cory Doctorow coined the term “enshittification” in 2022 to describe how online platforms switch from serving their users, to serving their business customers at the expense of their users, to finally serving only their shareholders, resulting in a poor service that both users and business customers are locked into. A similar process can be observed in the way technology is used to deliver services in our cities.

Airbnb is an undoubtedly useful platform for people looking for short-term accommodation for city breaks and holidays. When it was founded in 2008, it was celebrated as a means to connect individual travellers with homeowners who had space to spare, allowing users to bypass overpriced hotels and find affordable accommodation. On the face of it, this seems like a worthy endeavour, helping to connect people and to make more efficient use of available accommodation.

Fast forward seventeen years, and the impact of Airbnb on housing availability and on mass tourism is causing a backlash in cities across the globe. Barcelona plans to ban short-term rentals from 2028 in response to a housing crisis that has priced workers out of the market. New York City has introduced laws to restrict short-term lettings and block non-residents from letting out properties. Restrictions are also in place in Berlin, Lisbon, and Athens. Elsewhere, short-term lettings are highly regulated to limit over-tourism. Rather than connecting people, the rise of short-term letting has resulted in a sterilisation of parts of our urban centres where key-boxes proliferate and visitors never physically meet their hosts.

The plan for drone deliveries is just the next stage in a progression from takeaway restaurants doing their own deliveries, to online delivery platforms operating from dark kitchens. Again, it comes from a worthy pretext – to help restaurants connect with their customers and to make ordering takeaway food simpler for customers – but in this case, the enshittification stage results in streetscapes where restaurants no longer have a public presence, but are attended by gig-economy workers who act as intermediaries between businesses and citizens. The drone delivery concept goes one step further, replacing that human intermediary with a machine. The citizens of Dundrum certainly don’t see how that transaction is of benefit to them.

A similar progression can be seen from the redesign of our cities to suit the private motor car and the well-documented impact that has had on social interactions in the city, to the proliferation of ride-hailing apps, and now the notion that AI-powered driverless cars are the future of urban transport. Though the ride-hailing apps promised an end to congestion and reduced car ownership, the reality was very different – more congestion and more cars – and any system of AI-powered driverless cars will be governed by the same commercial imperatives to increase car miles on city roads. Again, where, in this, is the benefit to citizens?

A city is a community of citizens. At its core, it exists for the people who live there, and it thrives on social interaction. But what these technologies are doing, or proposing to do, along with things like self-service check outs, dark kitchens, and co-living units (which, despite their name, are fundamentally isolating environments), is to strip away that core. Removing human interaction in the name of efficiency and cost effectiveness is ultimately to the benefit of shareholders rather than citizens.

The Dublin city motto, “Obedientia Civium Urbis Felicitas” (Happy the city where citizens obey), has come in for some criticism recently. The Dublin InQuirer newspaper ran an unofficial poll earlier this year to choose a new, more appropriate motto for the modern city, and the winning entry changed just one word – “Participatio Civium Urbis Felicitas” (Happy the city where citizens participate).[4] That participation should be not just in the democratic functions of the city, but in the life of the city, in the culture of the city, and in the community of the city.

As we are assailed with technological solutions purporting to improve the lives of citizens, let’s consider them through the lens of the happiness of the city and its citizens. This is not a rejection of technology, but an acknowledgement that ultimately, technology should serve the citizens. If our cities are to thrive into the future, let’s recognise the importance of participation and prioritise measures that encourage social interaction and build social cohesion.

Ciarán Ferrie makes the case for more citizen participation in city life, culture, community, and democracy.

ReadWebsite by Good as Gold.