“Temporal depth” acknowledges the different levels of temporariness in a space. Our most-loved public spaces tend to have significant temporal depth, layering the distant past, recent past, and present to frame experience.

Take St George’s Market as an example, a popular covered market hall in central Belfast. Contemporarily, it draws crowds with the offer of live music and street food, however, these events do not sit in isolation and are enriched by the backdrop of a long-running produce market, where traders are able to trace family involvement for generations. Moving beyond living memory, the site has been a place for trade and the location of markets since 1604. This place of exchange has moved beyond an amenity and, instead, is integral to understanding local identity, with the surrounding neighbourhoods referring to themselves as the Market area. This is enabled by its longevity, with St George’s Market being the site of several notable civic events throughout history. For example, in 1834, the Northern Trade Union organised a meeting here of over 1500 people to protest the sentencing of the Tolpuddle Martyrs [1]. More recently, the market has hosted significant gatherings including the World Irish Dancing Championships and numerous conferences.

In the discussion of temporal depth, it is important to consider the related matter of civic involvement. Primarily, involvement requires action and reflection, thus civic involvement consists of acting and reflecting upon the ethics of holding a place in common with others, a core tenet of negotiating what it means to be a fellow citizen of a place. Civic spaces facilitate this involvement and can arguably be considered in one of three categories, adapted from those defined by Peter Carl [2]:

1) a civic space facilitates the encountering of other points of view;

2) a civic space supports constructive negotiation and;

3) a civic space makes possible the refinement of that negotiation.

Using the example of St George’s once more, illustrated is how the market creates the physical conditions required for people to come together within a civic space. Differing points of view are encountered via a variety of purposes: some people come to buy weekly groceries and others engage with temporary art exhibitions or browse souvenirs. Over time, rules of engagement have developed that allow for constructive negotiation between points of view, be that the etiquette of buying and selling produce, the preferred layout of the market stalls, and even the architectural restoration of the building. At St George’s, there is a Traders’ Association who work with Belfast City Council to define shared conduct at different levels, whether one is a visitor or host. As a result, there is a refinement of negotiation, ranging from temporary tweaks to more serious investment in the physical fabric – with a €3.5 million refurbishment in the 1990s being an example. In doing so, the environment has developed to facilitate and elevate a range of activities.

From the restored city motto “Pro tanto quid retribuamus” carved in stone, to the occasional upkeep of the carefully painted cast-iron columns, to the frequent upgrading of stalls and consistent cycle of their assembly and take-down, these routine adjustments give meaning and weight to the activities that take place within. Considering this, one can return to temporal depth and recognise that civic space requires certain features to remain indefinitely and others to be flexible and changeable. Importantly, it relies on both temporary and long-lasting architecture to contribute to the refinement of civic culture within the space [3].

Through using architecture with short, medium, and long lifespans together, we create cultural richness. Unfortunately, this approach to urbanism presents a stark contrast to our relationship with temporary architecture and urbanism in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. Here, impermanent architecture is all too often seen as an intermediary step prior to investment in something of higher quality in future. The rise in popularity of “tactical urbanism” is part of the problem: urban interventions that according to Lydon and Garcia are initiated by citizens to highlight “shortcomings in policy or physical design” or by local authorities as a public engagement tool to test aspects of a plan early “so that it’s easier to build great places” [4]. Significantly, the problem is exacerbated by the pressure to justify public spending on civic spaces against a numerical scale of achievement, which makes this type of urbanism very appealing to decision-makers. Tactical urbanism tends to have a particular goal, such as the introduction of a cycle lane or reduction in parking spaces, which is easy to measure and uncomplicated for a non-designer to understand.

To have tactical goals is commendable and sometimes much needed – as a designer, I am involved in several such projects. But the current default expectation of temporary architecture to act as a cheap prototype for long-lasting civic involvement undermines its true role in the making of civic spaces, thereby limiting the necessary investment in its quality and meaning. In my own practice, we try to address this by bringing the history of a place into conversation with the temporary installations that we place in it in order to contribute to a deeper civic involvement, beyond the life of the structure itself. In a city with a rich collective culture and a variety of spaces that support different kinds of civic activity, temporary architecture works with its surroundings, goes up, comes down, and moves around to make critical moments and cyclical events possible. It is not a stepping stone to a better, more permanent city, it is part of that better city.

One Good Idea is supported by the Arts Council through the Architecture Project Award Round 2 2022.

1. M.Chase, Early trade unionism: fraternity, skill and the politics of labour, Abingdon, Routledge, 2017, pp. 133-172.

2. J. Clossick, 'The depth structure of a London high street: a study in urban order', Doctoral dissertation, London Metropolitan University, 2017, p. 200; R. O'Grady, 'Collaborative heritage conservation in Tajganj: investigating civic possibilities in the urban order through architectural making', Doctoral dissertation, London Metropolitan University, 2018, p. 212.

3. M. Halbwachs, On collective memory, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1992.

4. M. Lydon and A. Garcia, 'A tactical urbanism how-to', in Tactical urbanism, Washington DC, Island Press, 2015, pp. 171-208.

Three seemingly unrelated stories caught my eye in the news in recent months. In the Dublin suburb of Dundrum, residents spoke out in opposition to a proposal to build an “aerial delivery hub” in the centre of the town.[1] A meeting organised by local politicians was attended by the chief executive of the drone company, but this wasn’t enough to convince the citizens of Dundrum that the new hub was a good idea.

A few weeks earlier, Irish billionaire businessman Dermot Desmond was reported as having described the long-awaited Metrolink project as obsolete and “a monument to history”.[2] He argued that autonomous vehicles operated by artificial intelligence would make the rail line redundant, would cut the number of vehicles on the road dramatically, and eliminate congestion. His argument was dismissed by transport experts and citizens alike.

More recently, in the annual scramble for housing, students in Galway spoke in despair about the lack of available accommodation, noting that there are currently over 1,000 properties listed on Airbnb for Galway, while there are only 111 properties to rent on Daft.ie (in fact, the figure maybe below seventy).[3]

What these three stories have in common is that they are all underpinned by technologies which aim to minimise social interaction within our cities, based not on a desire to provide a service to society (whatever their proponents might claim), but to extract maximum profit by eliminating the cost of people doing real work.

Canadian writer Cory Doctorow coined the term “enshittification” in 2022 to describe how online platforms switch from serving their users, to serving their business customers at the expense of their users, to finally serving only their shareholders, resulting in a poor service that both users and business customers are locked into. A similar process can be observed in the way technology is used to deliver services in our cities.

Airbnb is an undoubtedly useful platform for people looking for short-term accommodation for city breaks and holidays. When it was founded in 2008, it was celebrated as a means to connect individual travellers with homeowners who had space to spare, allowing users to bypass overpriced hotels and find affordable accommodation. On the face of it, this seems like a worthy endeavour, helping to connect people and to make more efficient use of available accommodation.

Fast forward seventeen years, and the impact of Airbnb on housing availability and on mass tourism is causing a backlash in cities across the globe. Barcelona plans to ban short-term rentals from 2028 in response to a housing crisis that has priced workers out of the market. New York City has introduced laws to restrict short-term lettings and block non-residents from letting out properties. Restrictions are also in place in Berlin, Lisbon, and Athens. Elsewhere, short-term lettings are highly regulated to limit over-tourism. Rather than connecting people, the rise of short-term letting has resulted in a sterilisation of parts of our urban centres where key-boxes proliferate and visitors never physically meet their hosts.

The plan for drone deliveries is just the next stage in a progression from takeaway restaurants doing their own deliveries, to online delivery platforms operating from dark kitchens. Again, it comes from a worthy pretext – to help restaurants connect with their customers and to make ordering takeaway food simpler for customers – but in this case, the enshittification stage results in streetscapes where restaurants no longer have a public presence, but are attended by gig-economy workers who act as intermediaries between businesses and citizens. The drone delivery concept goes one step further, replacing that human intermediary with a machine. The citizens of Dundrum certainly don’t see how that transaction is of benefit to them.

A similar progression can be seen from the redesign of our cities to suit the private motor car and the well-documented impact that has had on social interactions in the city, to the proliferation of ride-hailing apps, and now the notion that AI-powered driverless cars are the future of urban transport. Though the ride-hailing apps promised an end to congestion and reduced car ownership, the reality was very different – more congestion and more cars – and any system of AI-powered driverless cars will be governed by the same commercial imperatives to increase car miles on city roads. Again, where, in this, is the benefit to citizens?

A city is a community of citizens. At its core, it exists for the people who live there, and it thrives on social interaction. But what these technologies are doing, or proposing to do, along with things like self-service check outs, dark kitchens, and co-living units (which, despite their name, are fundamentally isolating environments), is to strip away that core. Removing human interaction in the name of efficiency and cost effectiveness is ultimately to the benefit of shareholders rather than citizens.

The Dublin city motto, “Obedientia Civium Urbis Felicitas” (Happy the city where citizens obey), has come in for some criticism recently. The Dublin InQuirer newspaper ran an unofficial poll earlier this year to choose a new, more appropriate motto for the modern city, and the winning entry changed just one word – “Participatio Civium Urbis Felicitas” (Happy the city where citizens participate).[4] That participation should be not just in the democratic functions of the city, but in the life of the city, in the culture of the city, and in the community of the city.

As we are assailed with technological solutions purporting to improve the lives of citizens, let’s consider them through the lens of the happiness of the city and its citizens. This is not a rejection of technology, but an acknowledgement that ultimately, technology should serve the citizens. If our cities are to thrive into the future, let’s recognise the importance of participation and prioritise measures that encourage social interaction and build social cohesion.

Ciarán Ferrie makes the case for more citizen participation in city life, culture, community, and democracy.

Read

Our bodies do the work, do we think of them when they are working?

Feet ache from standing, backs tire from lifting, shoulders ache from poor posture at a desk. We sit down, stand up, take a break, take refreshment. In some workplaces, there is consideration of the worker and their body: canteens are provided, bathrooms are kept clean, and the ergonomics of a desk are contemplated. All of this relies upon the acknowledgement of, the visibility of, certain types of work and workers. If we turn our attention to the city as a workplace – specifically, the streets, thresholds, parks and pavements that make up the public realm in the city and that act as a place of work for many workers – how does it accommodate the bodies of workers? Is it hospitable?

Over time, the perceived value of certain types of work, and consequently certain types of workers, has fluctuated. When seen as essential to the economy, to growth, the needs and availability of workers are considered, and their ability to advocate for better working conditions is strengthened. This has occasionally resulted in an architecture that responds directly to workers’ needs. We might take the example of pithead baths, communal bathing facilities that were built close to coal mines in the early twentieth century. Here, miners could change and bathe; the dust and dirt of the colliery becoming the responsibility of the mine itself and not the worker and their home. In Architecture and the Face of Coal: Mining and Modern Britain, by Gary Boyd, we follow the development and eventual obsolescence of this distinctive typology, pointing to the transitory nature of coal mining as one of the reasons for the short lifespan of the baths and for their fading from view in histories of modernist architecture in Britain.[i] So we have an example of an architecture that springs up in response to workers’ needs, but that also mirrors the changing status of the workers themselves.

The value of different types of work is something that we continue to grapple with and that contributes to inequality locally and globally. Precarity is widespread.[ii] Nowhere is the daily reproduction of the worker more difficult and given less consideration than in the city workplace. A conspicuous example of precarious and disembodied labour is the fleet of food delivery riders that has grown in response to the evolution of online delivery platforms. This new virtual infrastructure has resulted in, but takes no responsibility for, a workforce that is reliant on the fabric of the city. While there has been recent media coverage of the riders' problematic working conditions,[iii] there has been less discussion about the pragmatic and bodily realities of their work, where they contend with weather, traffic, criminality and so on.

In The Practice of Everyday Life, historian and cultural theorist Michel de Certeau sets out a model whereby power structures are discernible by the “strategies” of agencies and institutions, representatives of the state or of commercial interests; the organising logic of city planning, for instance, or the virtual frameworks that map, track, and influence. Against, or within, these strategies are the “tactics” of the other; the citizen, the customer, or, to employ de Certeau’s preferred term, the user.[iv] If we pay close attention to the city workplace, we start to see the “strategies” and “tactics” at play, the creative and opportunistic ways of “making do” that individual riders employ in their everyday life: they rest against walls and railings; they take shelter under canopies and in ad hoc repair shops; they take shortcuts, crosscuts over rainslick tracks or in the narrowing gap between a bus and a van; they take risks;[v] they sit on park benches and at the feet of statues.

At O’Connell Monument:

Do you eat your lunch here?

“Yes, this is my office chair.”[vi]

A warehouse on Henry Place holds a rental and repair shop, renting primarily to food delivery workers. The building is a protected structure that is decaying as it awaits a contested redevelopment.[vii] A single open space is divided into two zones by a low plywood barrier: public (for rental) and private (for repair). Bikes stand ready. Metal shelves along the east wall hold the accessories that might be required by a rider. In front, a desk where forms are filled and rent is paid. In a corner, some sofas face a TV screen. A fridge, microwave and kettle provide basic facilities.

On Henry Place:

Do you take a break here?

“Yes, this is the only place that we are able to eat because we rent the bikes here, so they let us use the microwave, the refrigerator... This is the only place in the city that we can have a little space together to eat something.”

On this backland site, a temporary and informal responsiveness is demonstrated. The city user improvises on the ground, while elsewhere, a debate rages about value. In contrast to the windowsills and kerbstones that are often places of momentary rest for a delivery rider, a dilapidated and impermanent structure gives a sense of shelter and retreat, making space for camaraderie and some degree of bodily comfort.

On O’Connell Street:

Do the delivery companies provide any equipment or clothes for you?

“Not exactly, once in a while they give something for free, like the bag and the jacket, but not all the time. The jacket is more for promotion; it gets wet, you get wet anyway. We have to be careful because we can get sick most of the time, because the rain makes our bodies very cold. We have to be extra careful when it’s wet.”

Where previous communities of workers had their needs considered, as in the construction of pithead baths for miners, for example, it was possible to point to a single employer with responsibility for the welfare of their workers. Groups of workers could agitate and negotiate for facilities, for practical solutions to tangible problems. Emerging from a pit with body and clothing covered in black coal dust led to straightforward questions about washing, changing, eating dinner, and storing clothes during the working day. Improvements in conditions for miners were realised because these workers were together, situated, and visible. Another historical example of situated workers’ facilities was the series of green huts built by the Cabmen’s Shelter Fund in late-nineteenth-century London. The shelters provided hot drinks and food, a place to read the paper for cab drivers, answering a series of pragmatic, corporeal needs. Like many Victorian philanthropic efforts, they came with an undertone of self-serving paternalism. Now with a protected conservation status, a handful of shelters are still in use, the interiors remaining the exclusive preserve of cab drivers.

Today, in corporate[viii] settings, the body is considered in great detail. Ergonomic assessments are exacting in their appraisal of a body at a desk: the length of shin (footstool), the height of eye (monitor stand), the reach and range of forearm (vertical mouse). Training is provided in how and what to lift. In theory, an employer is responsible for assessing these risks to the body regardless of the location of their employee. But in an era of modern piecework, who cares for the pieceworker? And is there a parallel between the hands-offishness of employers and our attitude to city streets and passageways?

Delivery riders are visible in the city but untethered, distributed through the network of the streets, finding their own informal gathering places. They are not employees; they are independent contractors. This status allows them to be light-footed within a network of regulations and legalities.[ix] The subcontracting of accounts with various delivery companies, for instance, results in a grey market of official and unofficial riders. These tactics have their mirror in the ways in which riders improvise occupation of streets and pavements, and act, to a degree, on the city; they are limited, however, in how they might shape the city to their needs.

Emerging from a tradition that prioritises urban commerce and suburban living, we plan for the street as a thoroughfare, an artery, thinking mostly of flow, of efficiency. There is arguably a parallel prioritisation of the commuter worker within the workforce. Certain dimensions are assigned for cars and buses, for bicycles and pedestrians to move seamlessly from the city centre to the periphery. This diminishes the value of the urban realm as a place to be, to dwell. What if we were to see (or return to) the streetscape, the weather-world[x] of paths, gratings and doorways, of tarmacadam and streetlights, as a single, integrated space that hosts diverse needs and functions, including those of city workers? The sense of the city as a place to move through can be challenged by an ambition to make a hospitable city: a place of rest, shelter and conversation. Acknowledging the public realm as a workplace might prove a catalyst for an inclusive approach to city-making, considerate of all bodies and all work.

Our bodies do the work. In this article, Anna Cooke asks: do we think of them when they are working?

Read

The Planning and Development Bill 2023 is currently making its way through the Oireachtas, with planning policy reforms focused on ‘efficiency’ to achieve growth. These reforms intend to streamline planning processes and accelerate decision-making. The consequence of a market-led approach to local planning is a reduction in the scope of citizens’ democratic right to have a say in the future of their towns and cities. The future system risks further limiting local debate over local change, while the current system fails to sufficiently harness local knowledge and invaluable stories of place. There is an alternative approach. In Ireland, there is an embodied culture of storytelling that naturally lends itself to a form of public engagement that creates space for dialogue.

‘Dialogue’ comes from the Ancient Greek ‘Diálógos’, where diá means ‘through, inter’, and lógos, ‘speech, discourse’. This definition could imply a concept of ‘talking through’. William Isaacs describes the word as ‘way to think and consider things together’.[1] In this sense, and for the purpose of this article, dialogue is comprehended as a means to understand others, but with no intention of achieving unanimity.

The treatment of time in planning processes often regards the future as a definite moment. There is an absence of the present and the everyday in spatial planning strategies.[2] For example, Dublin's six-year Development Plan sets out the long-term vision for the city based on a pre-established strategy, often lacking the ability to adapt to the complexity of changing global and local contexts. This inflexibility can lead to under-delivery of development, as the plans have little scope to deal with the unpredictability in shifting social relations. If strategic planning is a relational practice, how can planning and design processes embrace tensions between political expediency, bureaucratic vacillation, and urban realities?

Of growing concern is the trend within the planning systems of several European nations for neoliberal planning policies that favour private economic actors over public participation and discourse.[3] Such policies are underpinned by the accusation that ‘planning is an obstacle to growth’[4] and a rhetoric focused on the importance of ‘efficiency’ to achieve economic development. As a result, streamlined planning processes are justified by limiting the ‘barrier’ of public debate.[5]

These practices have been deployed by development lobby groups in Ireland to progress their objectives, contributing to the de-democratising of the Irish planning system.[6] According to the research, the narrative that convinced decision makers on certain planning reforms in Ireland – in 2017, the introduction of the fast-track Strategic Housing Development process, with applications made directly to An Bord Pleanála, bypassing the local planning authority’s decision-making role with no appeals process – were based on market solutions to problems traditionally addressed by public interventions, pursued by conflating the ‘collective good with efficiency’.[7, 8]. Swift decision-making equated to efficiency and the meeting of broader growth objectives. Whereas slow, deliberative, public engagement was perceived as an impediment, a problem to be solved through these planning reforms.

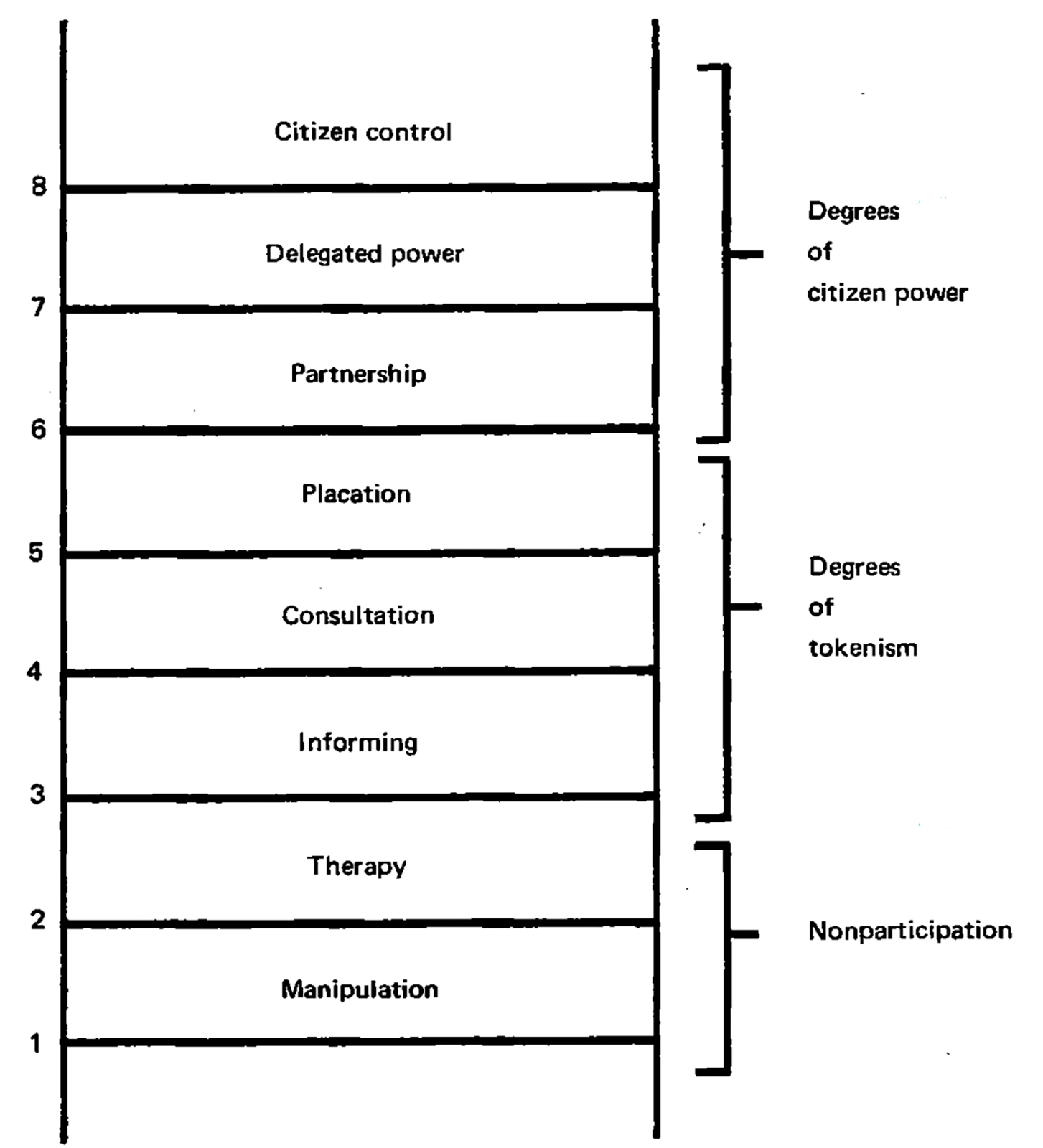

The objective of dialogue in planning processes is to increase pluralism and democracy. Citizen dialogues within planning processes have been established as a practice over the last ten years in Sweden. The use of ‘Citizen Dialogues’ in the Swedish planning system aims to include the public in decision-making, with this type of deliberative planning process encouraged before the statutory obligation of public consultation with various stakeholders. The ‘Citizen Dialogues’ guidance demonstrates how a dialogical method has been modified and adapted to meet specific needs and realities typical to planning issues, using Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation to consider the different stages of citizen engagement within the planning process.[9] This is practised through an acknowledgement of the fundamental importance of different perspectives of stakeholders.

Design in Dialogue, a book co-written by sociologist and urban planner Seppe De Blust, architect Freek Persyn, and architect, photographer, and mapper Charlotte Schaeben, also highlights how fundamental the ‘knowledge of many’ is in engagement processes.[10] Facilitating a form of engagement centred on lived experience allows for the diverse interpretation of realities. Both the Swedish model and the examples cited by De Blust, Persyn, and Schaeben emphasise how a dialogical approach can allow for alternative conversations that increase democracy in planning processes.

A recent report from the Aarhus Compliance Committee expresses concerns at some of the Planning and Development Bill 2023 contents related to public participation. Under the Aarhus Convention, Ireland has an obligation to comply with ‘The Public Participation Directive’ which states: ‘Public authorities should enable the public to comment on, for example, proposals for projects affecting the environment, or plans and programmes relating to the environment. The outcome of the public participation process should be taken into consideration in the decision-making process’.[11]

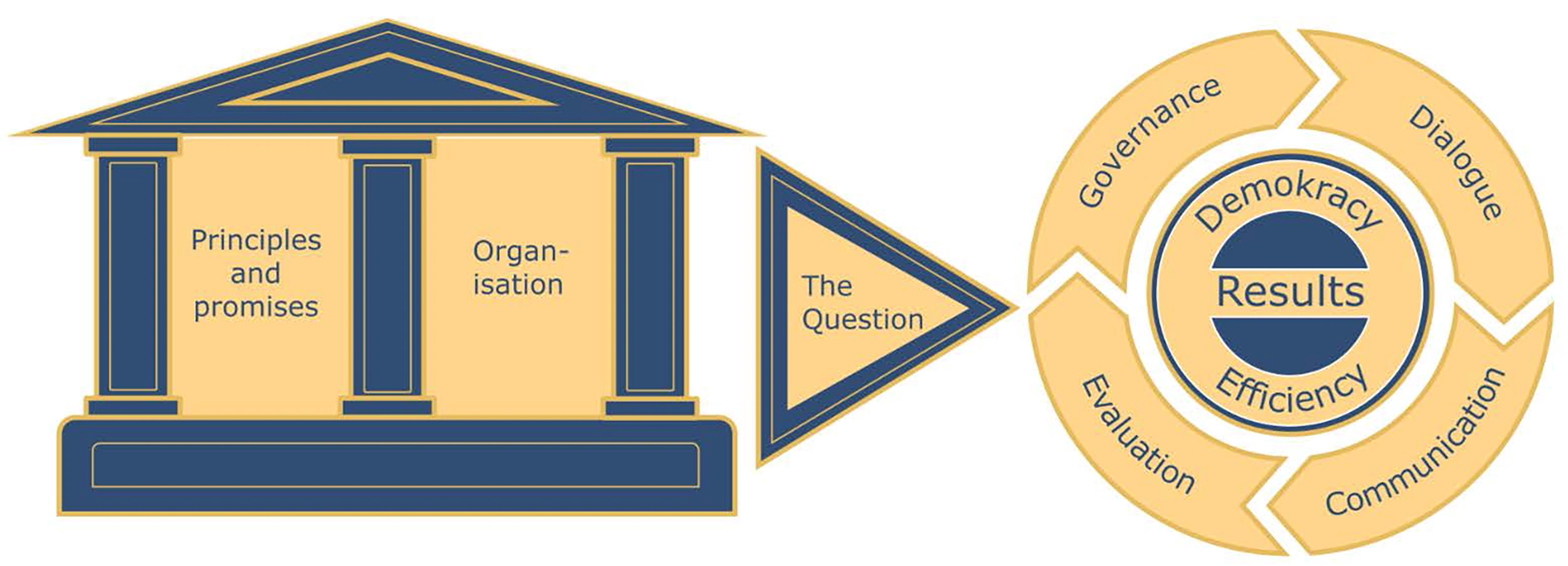

The question is, how could a form of dialogical engagement work in an Irish system that doesn’t allow for true public engagement? What kind of dialogical engagement would best suit the Irish context and who would carry it out?

One idea is to embed a dedicated role within the local authority that would carry out a type of engagement process that is focused on dialogue. In order to address concerns of diminishing public debate in planning, the role would have to be at the heart of the planning department, using the local authorities' in-house design and planning professionals and lived experiences in helping to define the role. The dialogue officer could be a facilitator between multiple stakeholders within processes linked to either planning policy or development planning. Their responsibilities could include community-focused placemaking; involving residents and businesses to collaborate in co-design processes; developing strategies for representing community voices in planning processes; and enabling community participation in the co-production of design proposals, masterplans, and polices.

The UK’s Public Practice, a not-for-profit job placement programme that guides the transition of built environment professionals from the private sector into public sector placemaking positions, is an example of an initiative that builds local authority capacity by supporting the creation of new roles. For example, community engagement specialists are embedded into the planning system, creating change that otherwise wouldn’t exist. The Greater London Authority's Placeshaping Capacity Survey 2024 report illustrates how Public Practice’s programme is the most valuable resource to placemaking projects in London, and notes that a programme of proactive planning allows for ‘better engagement and public support, provides greater certainty, and a more efficient process for developers, allowing for coordination of investment’.[12]

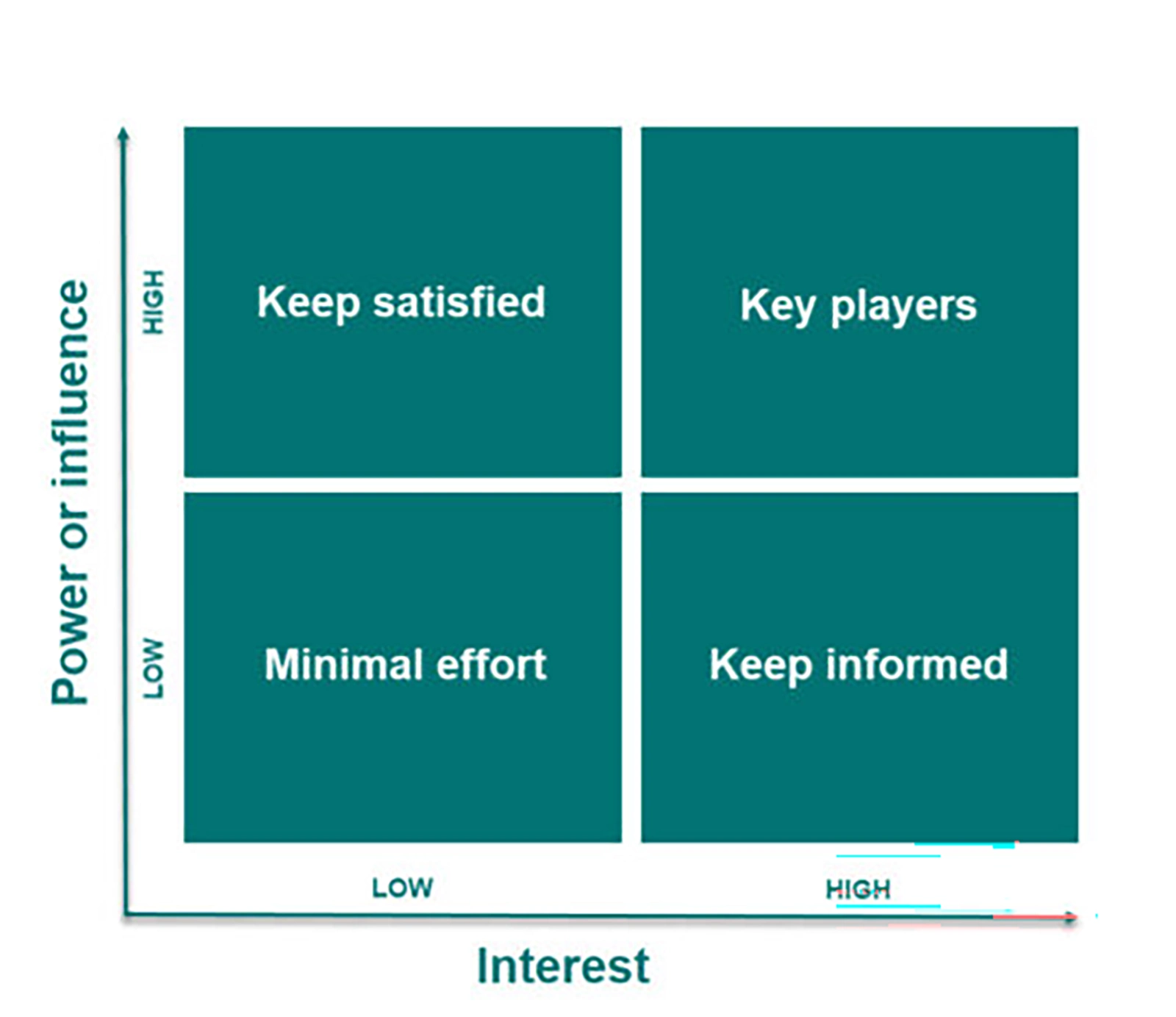

A new role in the planning team that facilitates a form of dialogical engagement would require an understanding of the power structures present in the planning process from the perspective of each of the different actors experiencing that particular planning process. For example, in development planning, there is a need to negotiate the varying interests and controversies among citizens and stakeholders at pre-application stage prior to submission. Mendelow’s Matrix can guide a mapping analysis of these relationships in terms of interest and influence over a project. Understanding the power structures and relationships between stakeholders with diverse positions allows consideration of how conversation and understanding between key actors may be enhanced. While these dialogues may not lead to concrete outcomes, they can facilitate a sharing of knowledge and lived experience between different stakeholders that otherwise, would not exist.

The purpose of a dialogue role would be to address the dominant market-driven, decision-focused city-making processes that often overlooks local lived experience. A dialogue officer could facilitate a continuous form of engagement throughout the planning process, as opposed to engagement that comes at the end of the process, like the current system of public observations upon submitted planning applications. As uncertainty in decision-making is in conflict with the current pace of the planning system, could dialogue be used in an Irish context as a tool to increase pluralism, representation, and democracy in planning processes, and ultimately – by reducing conflict – support a more streamlined decision-making process?

In the context of planning reforms focused on 'efficiency', Sophie El Nimr argues instead for a new, dialogue-focused mode of public engagement with planning processes in Ireland.

ReadWebsite by Good as Gold.