Planning systems tend to be better at preventing what they don’t want than enabling what they do want. The Planning and Development Bill is process-driven: it is to be hoped that its effects on the practice of architecture – on how we move between design stages – will be positive, but we shouldn’t look to it for design intent. Indeed, the component of the Bill that might most effect how we design is notable for its lack of detail. Urban Development Zones (UDZ) have the potential to change how and what we design. They define a mechanism by which the planned use of lands is specifically designated by local authorities with early public engagement to restrict what landowners can do with land within these zones, unless they accord with the designated intention. UDZs potentially move power back to public authorities to say what is developed; they could take Ireland toward much-envied Dutch or German models of development. Housing for All – the source of the UDZ concept and one of three docments that arguably most influence what we design [2] – limits its concerns to only one sector of the built environment: housing. For a broader demonstration of planning intent, we need to look to the National Planning Framework: Ireland 2040 (NPF) and the Climate Action Plan.

The Climate Action Plan – across its 2019, 2021 and 2023 iterations – is clear in its intent. An urgent response to the climate crisis is required. Across various sectors it describes change needed and pathways to achieving this change. Spanning from the level of the building in its development of performance standards and its promotion of low-carbon construction, to the level of the settlement level in its creation of pathfinder decarbonising zones, the Climate Action Plan’s implications for design are huge – a root and branch reassessment of the energy we use, not just to heat, cool, and light our buildings, but in the production and transport of construction materials, construction processes, maintenance, repair, and disposal of buildings and infrastructure. Notwithstanding this, spatial planning, design, and architecture are only a small part of the Climate Action Plan’s concerns.

Planning in Ireland is based on the principle of subsidiarity – decisions should be made at the level closest to their effect. To understand the effects and intentions of planning toward design, we need to start at the top of the spatial planning hierarchy with the National Planning Framework ‘Ireland 2040’ and follow its vision down to the local level. The NPF describes intentions at the national level for how and where we design: a compact growth model of higher densities mostly within existing urban footprints; the growth of Dublin to be equalled by the combined growth of other cities; the combined growth of all Irish cities to be equalled by development directed towards key towns across the country. The Ministerial Guidelines that followed the NPF described in more detail what this compact growth model should look like in terms of densities related to transport connectivity, and what this might mean for forms of development. Having filtered down through the Regional Assemblies to work out the numbers, these national intentions find expression at the local level where their effects will be experienced as described by County or City Development Plan.

The final document referenced here, Places for People: The National Policy on Architecture, makes important commitments to fostering a culture of architecture Ireland. It recognises how crucial design’s role will be in achieving the aims of the National Planning Framework and the Climate Action Plan in an equitable way across Irish society. Places for People reaffirms why architecture is important; Ireland 2040 tells us where and how it will be located.

This returns us to Sorkin’s maxim. Architecture sometimes is participatory to varying levels, but it is not required to be. Design has no inherent analogue to planning’s subsidiarity. The statutory processes of planning are the mechanism by which concerns regarding the common good are brought to bear on the potentially individualised practice of architecture. Proposals are approved or rejected based on their compliance with local development plans which, for at least twenty years, have been placing increased emphasis on describing their intended built environment – not just development standards, but urban structure, quality design, healthy place making, and sustainable neighbourhoods. The effects of architecture, in other words, as described by Places for People.

If together this demonstrates that encoded within the suite of documents the NPF oversees are a set of intentions toward architecture and design, can anything be said of its effects? No, not yet. The NPF has yet to reach its first review; the first generation of development plans that follow it have only recently been agreed. Instead, it may be more beneficial at this stage to push farther into the question of intentions. Since architectural quality largely remains absent from development management functions of the Irish planning system, how can a degree of design control be provided, responsive to the needs of the common good, as exemplified by the principle of subsidiarity?

The failures of past models of urbanism need hardly be rehearsed here. Suffice to say that should architects, urban designers, and planners ever feel the urge to act as boosters for good intentions (over their failure’s very real social effects), they ought to keep a copy of poet Caleb Femi’s collection Poor to hand. A reflection on a childhood spent on the notorious and now demolished North Peckham Estate – described by Jonathan Glancy as the Athens Charter built ‘too quickly, too cheaply, too brutally and without the necessary skills’ [5] – Femi’s ‘A Designer Talks of Home/A Resident Talks of Home’ [6] should make even the most ardent evangelic formalist pause.

Can we perceive within the foregoing an intention to limit architecture’s ability to experiment at scale? Probably yes, and not unreasonably: credit effects, not intentions. But experiments at scale gave us Barcelona’s Eixample, wherein a new model for urban expansion has provided near limitless variation at the level of the building plot, the urban block, and now the superblock.

What is the effect, if in our intentions toward architecture we are ‘too suspicious of formal experiment and overly sanguine about the dispensability of architecture as an artistic practice?’ [7]. We avoid Femi’s North Peckham estate, sure, but we also miss out on Cerda’s Eixample.

Future Reference is supported by the Arts Council through the Architecture Project Award Round 2 2022.

This year’s presidential election made visible a dynamic that is often overlooked in political analysis: how campaigns operate as a form of civic infrastructure, and to what extent design plays a role in their efficacy. Far from being peripheral or decorative, the visual strategies deployed by candidates’ structure how people encounter political life; they shape perceptions long before policy is discussed or manifestos are read. Political design occupies a unique position within democracies, somewhere at the intersection of communication, civic identity, and public trust.

In Ireland, this relationship between design and democratic expression has been strained by a decades-long pattern of executive neglect. Successive governments have systematically deprioritised design and aesthetic quality in public communication and built infrastructure. Senior ministers increasingly frame design as an optional consideration, an unnecessary add-on rather than a fundamental part of how the State articulates care, competence, and regard for its people. As Minister for Public Expenditure Jack Chambers stated during a debate concerning escalating costs at the National Children’s Hospital (NCH), ‘there needs to be much better discipline in cost effectiveness… That means making choices around cost and efficiency over design standards and aesthetics in some instances’ [1].

This position, widely cited and contested, exemplifies a broader ideological shift which sees design treated as a dispensable luxury rather than an essential civic tool [2].This framing misunderstands the function of design within public life. Design, in this case, is not ornamental; it is a mode of communication through which the State makes itself legible. When design is neglected, the consequences extend far beyond the aesthetic and shape the conditions under which political meaning, public trust, and civic visibility are formed.

In the aftermath of Catherine Connolly's election as President, commentators highlighted the design and visual expression of each candidate as decisive factors [3]. Connolly’s campaign offered me a rare opportunity to explore what an authentically Irish political visual identity might look like when grounded in cultural memory rather than branding for the sake of visuals alone. While designing, I drew directly from Ireland’s vernacular signwriting tradition: the hand-painted shopfronts, gilded fascias, and serifed letterforms that once defined the visual texture of towns and villages. These were not simply aesthetic references. They embodied authorship, locality, and a sense of civic care.

By incorporating hand-drawn lettering, a deep green and cream palette, and a postage-stamp motif, the campaign sought to restore the tactile warmth and humanity often lost in contemporary political design. The stamp, a quiet symbol of communication and exchange, is a reminder that politics is, at its core, a conversation carried between people. This concept frames Irish craft traditions not as relics, but as living cultural practices capable of shaping contemporary civic discourse.

In doing so, Connolly’s campaign made design itself an act of cultural continuity, a way of honouring the past while proposing a more grounded and participatory future. By the time Connolly declared on election night, “This win is not for me, but for us,” the sentiment had already been woven through posters, leaflets, and social media, a visual testament to a campaign that made the collective visible long before the votes were counted [4].

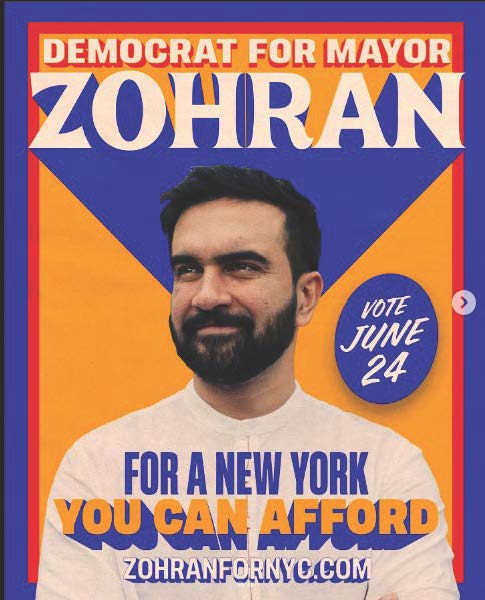

Across the Atlantic, Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral campaign in New York City attracted attention first for his democratic socialist views. It was the striking coherence of his campaign design, however, that propelled him into broader public discourse. Not since Shepard Fairey’s Hope poster, for Barack Obama, had a political image circulated so widely. It gained the kind of immediate recognition associated with Jim Fitzpatrick’s image of Che Guevara.

The Mamdani campaign was intentionally rooted in the material and cultural vernacular of the city itself. The cobalt blue and yellow palette was drawn directly from everyday sights in New York: bodega awnings, taxi cabs, MetroCards, hot dog vendors, and the signage of small independent businesses [5]. In this way, the campaign aligned itself with working-class infrastructure that defines the city’s public life, situating Mamdani not as an outsider but as a candidate embedded in the city’s social, cultural and economic rhythms [6]. Central to this strategy was the premise that design could serve as a communicative bridge to the constituency Mamdani sought to represent. In doing so, the campaign framed visual culture as a mode of continuity and care, a reminder that political communication can affirm belonging as powerfully as it persuades.

Irish election materials, as well as the State's political design more generally, don't attempt to convey substantive meaning through visuals. Their long-standing reliance on formulaic portraiture, generic slogans, and minimal graphic refinement mirrors a broader campaign strategy in which candidates are packaged as approachable local figures using highly-conventionalised visual cues. This approach reduces design to a mechanism for name recall rather than a vehicle for articulating political values or fostering civic engagement. The environmental waste associated with poster production only heightens the sense of outdatedness and underscores how Irish campaign materials often lag behind the more considered, narrative-driven strategies emerging elsewhere. As such, this tradition of visual identity crystallises the limitations of Irish political branding: a dependence on repetition, familiarity, and low-risk aesthetics at the expense of meaningful visual communication.

A strong democracy depends on sustained, accessible dialogue between the State and its people. Visual identity is structurally embedded within this exchange. Visual languages that are familiar or culturally resonant reduce cognitive load and strengthen affective engagement, whereas generic or stylistically flattened forms tend to weaken meaning-making [7]. In this sense, campaign aesthetics function as a form of civic infrastructure, shaping perceptions of authority, intention, and legitimacy before a single word is spoken.

When design is framed as a luxury rather than an essential component of civic life, it erodes the shared visual language through which democratic communication occurs. Such an approach initiates a feedback loop. Minimal investment in design yields fewer meaningful symbolic or material expressions of public life. As these expressions diminish, the State becomes increasingly illegible to its people. Over time, the corporeal presence of the State, its visibility in the everyday, degrades. What was once a free-flowing dialogue becomes generic, flattened, and emotionally inert. Political branding therefore mirrors the State’s broader orientation toward public infrastructure. When design is treated as secondary, a dispensable aesthetic layer rather than a civic medium, its communicative and democratic potential collapses. When taken seriously, however, design becomes a point at which cultural belonging, political intent, and civic participation converge.

Ireland’s future civic health depends not on dispensing with design but on recognising it as a central component of public life. It is the medium through which the State becomes visible, legible, and trustworthy.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Highly visible and emotionally charged, electoral campaigns are often the first instance in which a state’s people encounter their elected representatives. In this article, Anna Cassidy, designer for Catherine Connolly's presidential campaign, examines how political design is indispensable to the democratic process.

Read

“[W]asn't this all started by some terminally online moron in trinity? … Nobody gives a shite so long as the statue isn't actually being damaged” wrote [Deleted] on the reddit page r/Ireland in a thread to discuss Dublin City Council's proposals to stop the repeated groping of the Molly Malone statue on Suffolk Street — her breasts repeatedly touched by the sweaty hands of tourists, so much so that the dark patina has been worn away to reveal the earthy metallic dark orange of the bronze from which the mythical fishwife was cast. Thousands of images of Molly #mollymalone circulate on TikTok. A group of men dressed in Jack Chalton-era Irish football jerseys stand in line to rub their faces in her breasts. In the comments section one user posts, “reminder she’s 15 in this statue,” others disagree, claiming she was older, as if somehow the behaviour would be permissible if the statue represented Molly as 17 – the legal age for consenting sexual acts. Others use the platform to protest the behaviour.

If you ask Google’s AI Gemini about the practice, it tells you that “this practice is now discouraged by authorities for preservation reasons.” This is artificial stupidity, a view blind to a far more important problem, one that philosopher Sylvia Wynter described as an urban planning that assumes the male-coded subject as the norm, while others—women, Black, Indigenous, and colonised peoples – are excluded, marginalised, or rendered invisible [1]. For Wynter, urban space is ontologically male, in that its logics of design, governance, and belonging reproduce a gendered and racialised “Man” as the universal standard of being. Speaking to RTÉ Radio One, DCC Arts Officer Ray Yeates (a man) suggested that one solution could be to “just accept that this behaviour is something that occurs worldwide with statues” – human stupidity [2]. Perhaps Yeates might agree to a plaque being added, inscribed with a quote from Wynter: “Man …overrepresents itself as if it were the human itself”[3].

As images of the statue circulate online, they both promote and raise awareness of this deleterious practice. But this is the means and not the end of their circulation. These images turn Suffolk Street into a space for the production of a strange kind of economic exchange. With one sweaty hand on a breast, and the other on a smartphone, tourists become workers. Here, as in all of everyday life, a distinction can no longer be made between work and play. In our age of contemporary digital technology all of everyday life is a factory. To play is to work; the digital proletariat; to use a technological prosthesis is to be used by that prosthesis. These interfaces, designed for the many by and for the benefit of the few, manage life by means of ‘fun’. Spaces like Suffolk Street are, as Letizia Chiappini writes, where “[a]ffect, desire, pain, and love, are digitally mobilised for direct spatial impact” [4].

Henri Lefebvre called this abstract space – “[t]he predominance of the visual (or more precisely of the geometric-visual-spatial)” [5]. He described this kind of logic as a planetary mesh that has been thrown over all space [6]. Any space, anything, anywhere, no matter how banal is subject to this logic. 13,461 km away from the Molly Malone statue is an underpass in the Chinese city of Guilin. Each night crowds of outdoor live streamers gather to steam content on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), their faces glowing in the phosphorus white of selfie lamps. Geolocation means that if they are closer to more prosperous neighbourhoods then they make more money from the wealthy clients who live there. These leftover urban spaces that are seen as unattractive and once disregarded in a capitalist economy have become spaces where new economies and ways of working emerge. I have written elsewhere about the disproportionate role that Ireland plays in facilitating the infrastructures that produce these kinds of spaces [7]. This is a new kind of geopolitics, one facilitated by State fiscal policies, such as in Ireland, home of one of lowest standard corporate tax rates in the EU.

This is capitalism incarnate – capitalism become flesh. Everything has an exchange value. There is not a thing that cannot be transformed into a commodity to be circulated in an economy of flesh, thoughts, drives and desires. This is an economy governed by images, subject to what legal scholar Antoinette Rouvroy calls algorithmic governance – the governance of “the social world that is based on the algorithmic processing of big data sets rather than on politics, law, and social norms” [8]. The statue of Molly is a public surface subject to an extractive logic, via the lens she is engineered for constant circulation, interaction, and capture. The statue as code has her meaning flattened into content for the purpose of data extraction and ad revenue. This kind of collapsing together of work and leisure is a weapon of mass distraction. It removes us from everyday life, producing what philosopher Henri Lefebvre called a “transcendental contempt for the real” [9].

Lefebvre also called for a right to the city, by which he meant the right to the production of truly democratic space. Space that is not subject to capitalist abstraction. To what extent this is even possible in our precarious age of algorithmic governance is questionable - but nonetheless we must seek to understand, hope and act.

The groping of the Molly Malone in Dublin reveals a complex new urban condition – the algorithmic production of space. Social media, viral images, new modes of capitalist production, foreground the emergence of an entirely new logic of spatial production. What does this mean for the possibility of a right to the city?

Read

On visiting the Villa Tugendhat in Brno, one might be struck by a couple of things. First, on entering the building, the air in the hallway is stale, a result of the inoperative original air-conditioning system. Secondly, the planning of the basement service floor is surprisingly chaotic. These two observations suggested to me a narrative about modernism’s dependence on technology and about Mies’ attitude to that technology – and the situation of architecture in general in relation to technical measures.

Mies worked in more than one register when designing the villa. The top floor, with the entrance hall and bedrooms, is fairly straightforward: lucid and rational. The floor below, what I suppose in German could be called the Beletage, has a flowing and expressive plan comparable to his single-storey Barcelona pavilion. Like the Barcelona pavilion, it has a representative purpose: it contains spaces for entertaining, constructed with fine materials which convey the wealth of the inhabitants. The basement below is half-buried in the hillside and contains mostly service spaces. The layout of the basement feels strikingly unresolved in comparison to the other floors.

The plan of the basement is not often published. It contains, among other things, a boiler room, a laundry room, the room-like processing chambers of the air conditioning system, a photographic darkroom for Mr Tugendhat, and a “moth chamber” where fur coats were stored. These functions are arranged in a way that is partly determined by the layout of the floor above. For example, the dumb-waiter is at the end of a narrow corridor around which a contorted storage room is wrapped. It’s as if the occupants of the basement scurry around this warren of spaces to pick up the loose ends of the freely-planned floor above. There is no functionalist virtue on display here. Indeed, the tiled and napthalene-impregnated moth chamber, accessed through the darkroom, is at the end of a chain of five rooms. It gives a claustrophobic impression tainted by the idea of moths as vermin, and of a cruel method of industrial extermination. The technology of circa 1930 is reflected in the primitive air conditioning system: a piece of apparatus firmly fixed in history, but one in service of the apparently timeless perfection of the upper floors.

It seems that Mies did not consider the basement floor to be part of his architectural expression. He didn’t optimize it. The terse open-plan geometry of the main living spaces reflects not just freedom of movement for the inhabitants, but Mies’s freedom of design. It is simple in comparison to the complex technicalities of actually keeping the house running.

The closest thing the villa has to a centrepiece is the orange onyx wall, non-load-bearing and composed of five slabs. While one could interpret this as a pure display of luxury, it is also an object of contemplation (or at least a talking point). The Tugendhat family were cultured as well as wealthy, and I want to attribute to them some kind of elevated curiosity about this object. What can we recover, in the way of intellectual depth, from reflecting on the onyx slabs? A suitable source might be the French philosopher Roger Caillois, who, in his book The Writing of Stones [1], discerned in geological patterns “some ancient, diffused magnetism; a call from the center of things; a dim, almost lost memory, or perhaps a presentiment, pointless in so puny a being, of a universal syntax.” In relation to the Villa Tugendhat, where the setting sun causes the backlit onyx to glow translucently, Caillois’s words evoke an understanding beyond the codes of architectural modernity. Mies’s obsessive refinement of his constructional poetics certainly has something to do with striving for a universal syntax, and the connotations of cosmic grandeur must have been intended as well, but the awkward, “puny” insignificance of humanity, in contrast, doesn’t seem to find a direct expression in his design. A stone is an indifferent thing.

Caillois wrote “Life appears: a complex dampness, destined to an intricate future and charged with secret virtues, capable of challenge and creation. A kind of precarious slime, of surface mildew, in which a ferment is already working. A turbulent, spasmodic sap, a presage and expectation of a new way of being, breaking with mineral perpetuity and boldly exchanging it for the doubtful privilege of being able to tremble, decay, and multiply.” [2] Although Caillois did not have architecture in mind, these vivid words evoke, in contrast to the timelessness of the onyx wall, the more fragile reality of the Villa Tugendhat, a reality of uncertainty that undermines Mies’s confident form-making. At the most basic level, the presence of humans means the presence of water vapour and all manner of microbial impurities. These are perennial problems for the architect: problems of climate control and hygiene. The handling of the response to them (the concealed inventions and intricacies of the air conditioning equipment) is arguably a truer token of humanity than the stony perfection of polished onyx panels.

The flight of the Tugendhat family from Brno in 1938 in the face of the impending Nazi occupation is emblematic of the precariousness of civilization and of an industrial society gone astray. The grand formal spaces of the villa have an appropriately monumental character, as Mies intended, but the technical floor tells another story of historical contingency, unresolved difficulties, and of all the problems we try to sweep under the carpet.

Editor's Note: An exhibition on the architecture of the Villa Tugendhat will run in the Irish Architectural Archive from January to March 2026.

Throughout its evolution, architecture has been required to engage both with imperfect technologies and the contingencies of life. This is clearly evidenced in Mies Van der Rohe’s Villa Tugendhat. The villa has a public face of rare perfection, but other aspects make one wonder about the architect’s ethical stance in relation to functionalism and humanity.

ReadWebsite by Good as Gold.