‘It is indeed by uneasy steps that the pub has wandered through the paths of history, buffeted by storms of public controversy, assailed by the slings and arrows of temperance reformers, sometimes harassed, and sometimes supported by instruments of legislation. That it has survived in so ubiquitous a way is remarkable’ [1].

The success of the architecture of Victorian Dublin is typically understood through the grandeur of the Curvilinear Range at the Botanic Gardens, the Reading Room at the National Library or perhaps the Museum Building at Trinity College, each an example of intricate architecture, engineering, and craftsmanship. Deane, Woodward, and Turner are rarely forgotten in the discourse around the built fabric of Victorian Dublin, nor are Harry Clarke, the O’Shea Brothers or Carlo Cambi. However, this article focuses not on such grand artefacts and their architects. Instead, it is inspired by Dublin’s sixteen remaining Victorian pubs [2].

This visual essay takes The Swan Bar as a case study and aims to highlight the wealth of materiality to be found in these pubs, enjoyed by generations passing through. This map highlights the sixteen remaining Victorian pubs across the county of Dublin.

The Sixteen Victorian Pubs of Dublin

The Swan Bar (Lynch’s of Aungier Street)

The Swan Bar on Aungier Street in the heart of the city centre takes its patrons on a journey of materiality: mahogany, mirror, mosaic, clocks, brass, stained and tinted glass. Owned and run by the Lynch family for generations, the original materials which have remained in place from its 1890s refurbishment bear visible representations of the time that has passed. The tile and timber floor, patched in places, slightly sunken in others, is both a testament to its original craftsmanship and a palimpsest displaying evidence of former configurations. Quality materials not only last the test of time but often improve; a mahogany handrail is worn smooth by the million hands that have run across it. These architectural details were crafted with care and yet made to endure the thumping, scratching, cleaning, and polishing we have done for over one hundred years.

Under the front window where there now sits a cosy snug, a tea shop once faced the street. A common feature of the Victorian pub was to lend its shopfront to the selling of groceries - further suggested by the call bells in brass on mahogany and pitch pine. Division and threshold are strong features of the Victorian pub, and The Swan is no different. Within the central aisle, a forgotten porch is inscribed on the tiling revealing a large depiction of a swan which one would otherwise encounter upon entry. This patina allows for immersive engagement with the pub's history, going beyond appreciation for the craftsmanship itself.

It's an easy thing to romanticise Victorian craftsmanship. In reality, the maintenance of these buildings poses its issues, with contemporary publicans often having to navigate tricky legislation surrounding protected structures. The reasons for repairs vary, from obsolescence and natural decay, to wear and tear and intoxicated disregard. The manner and material of replacement speaks to the priorities, interest, and means of the owner. In the case of The Swan, the damaged yet original tile work tells of the stabilisation works undertaken beneath the ground floor, and a scratched mirror tells of blatant vandalism. While there is no lack of interest on the part of the owner, replacing triple bevelled mirrors and yellow stained glass panes, and bringing original brass pumps back into use is additional to the everyday demands of the service industry. Irish Licensing World claimed ‘A publican must be a democrat, an autocrat, an acrobat and a doormat’, in order to manage the wear of these pubs and fulfil contemporary conservation requirements; that list could continue [3].

There is a balance to be struck between reconfiguration to fit current purposes and the erasure of former use. A surface on which to light a match can be rendered obsolete by the lighter, a cashier's kiosk by modern-day payment methods, a whiskey cask by bottled spirits. While these physical Victorian details may be anachronistic, they add to the experience, as do the clock hanging centrally above the bar and, importantly, the Scottish granite countertop to keep a resting pint cool. Whether functionally obsolete or not, their presence ought to be valued by the publican and appreciated by the patron. The decision to retain such details is not driven by nostalgia but by appreciation of craft, in seeing the hand of the craftsperson in the everyday.

As artefacts in themselves, in their ornamentation and craftsmanship, these pubs should be valued. The decay and destruction of the city in the lifetime of these pubs is starkly contrasted by their permanence both materially and in operation. Their provision of an ‘escape from bleak tenement life’ and ‘a surrogate domesticity’ suggest that they were as rich and lavish an oasis then as they feel today. These materials, explored in the photographs below, offer a window through which we can gain another perspective on Victorian Dublin, scarred, rounded and smoothed by time. It is through our patronage that these pubs will continue.

.jpg)

Open Space is supported by the Arts Council through the Architecture Project Award Round 2 2022.

1. K. Kearns and R. Rinehart, Dublin Pub Life and Lore: An Oral History, Dublin, 1997.

2. K. Kearns and R. Rinehart, Dublin Pub Life and Lore: An Oral History, Dublin, 1997.

3. K. Kearns and R. Rinehart, Dublin Pub Life and Lore: An Oral History, Dublin, 1997.

4. N. Booth, ‘Drinking and Domesticity: The Materiality of the Mid-Nineteenth-Century Provincial Pub’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 2018, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 289-309.

Most people call it crypto but for the purposes of this exercise we’ll use the term "blockchain".

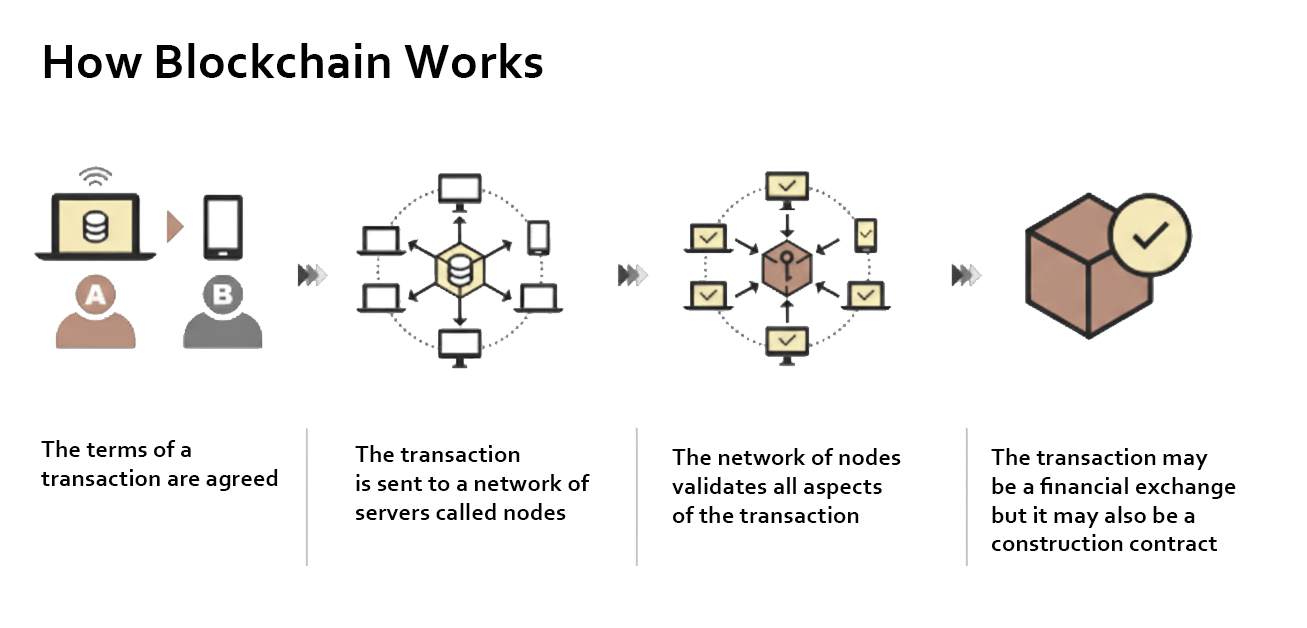

At its core, a blockchain is simply a way of recording an event on a digital ledger instead of in a paper document. This could, for example, be a record of an agreement - the kind of agreement people have been making between one another for as long as agreements have existed. If you do X, I’ll do Y. In the past, we’d make the agreement official by signing some papers in a solicitor’s office. However, with a smart contract running on a blockchain we take a different approach: first, we set out all the conditions that have to be met before the contract can be entered into; then, instead of asking a solicitor to decide when these conditions have been met, we write the whole thing in computer code and let technology act as the referee. The terms of the agreement are implemented without fuss and in a way that’s difficult to undo. If I suddenly get cold feet about some commitment I may have made, I can’t wriggle free of my obligations by finding loopholes and stirring up trouble. That’s the first interesting thing about a typical smart contract: terms and conditions are fairly hard wired.

The second interesting thing about blockchain contracts is the way details of the agreement are stored. Once the computer confirms that all the conditions have been met, the record isn’t just dumped onto one big central server which would be an obvious target for hackers. Instead, a copy of the entire record is kept on many different computers (nodes) spread out around the world. Each copy is kept in a series of linked “blocks” and each block contains a sort of digital fingerprint of all the verified information on which it is based. If someone tries to change even the tiniest detail in one block, the fingerprints won’t match and the change will be rejected. For extra security, large files (a good example for our purposes would be contract drawings) can be stored separately using a system like IPFS. The main block can be primed to keep an eye on these files to make sure that important material hasn’t been tampered with.

It didn’t take long for the earliest blockchain experimenters to see how this new technology could work as a form of money. Money, after all, is just another type of agreement. And so, around 2009, the terms "Bitcoin" and crypto entered the public imagination. Almost immediately, Bitcoin became synonymous with dodgy financial dealings and the internet was soon full of stories about international criminal gangs getting around banking regulations by paying each other in this new invisible currency.

But if we ignore all the hyperbole and look again at what an Ethereum-type blockchain involves – a system that has the same secure, tamper-proof data blocks as Bitcoin but also supports smart contracts – you can see how it might be used for things far beyond dodgy money. Anything that needs a secure, verifiable agreement could benefit from a blockchain approach, including many of the processes that underpin building and construction.

One of the more interesting examples so far of the use of blockchain in the broader construction/real estate space has been in property transactions and land registration. Anyone who’s ever bought a house, no matter where, will know that the process is slow, bureaucratic, paper-heavy and prone to error. Blockchain offers a secure, transparent alternative. In recent years Georgia (the country, not the US state), Dubai, Sweden and other jurisdictions have been testing out blockchain systems to record transfer of title. Media reports suggest the trials have been generally successful with transactions being completed sometimes in a matter of minutes.

In construction, the potential is just as easy to imagine. Take the example of a contractor completing the installation of a complicated foundation on a new project. Instead of waiting weeks for manual inspections to take place, on-site sensors confirm in real time that the work meets the agreed technical specification. That verification is automatically logged on a blockchain, which triggers immediate payment. Large companies like Skanska and Bechtel have been experimenting with these and similar approaches for quite some time, tracking materials from their source to their final installation as well as checking authenticity and compliance.

Another interesting area for potential blockchain crossover is the use of BIM. In a big public building project the architect, engineers and contractors might each start out working on the same 3D BIM model. But as the job progresses, each consultant makes one tweak here and another one there and soon various "official" versions of the same model have come into existence. When a dispute eventually erupts over whether a particular detail was formally approved, no one can be sure whose version of the detail is the “real” one.

With a blockchain-based approach, each approved version of the BIM model could be time-stamped and stored in a tamper-proof way so that a clear, verifiable record of what was agreed can be referred to. We could take this concept one step further and link the approved building model to a city’s digital twin – say, Dublin or Cork – with the building’s latest data slotted straight into the digital city model. This would mean that planners, utility providers and emergency services would have a reliable, up-to-date digital version of the building to work from. And, in fact, this is something that is already being explored in Dublin where the City Council’s partnership with DCU on creating a digital twin has received favourable coverage in the trade press.

While there has been progress in these and other areas, particularly in the private/commercial sphere, wide-scale adoption of blockchain technology in the worldwide construction industry faces a number of hurdles. For a start, regulations vary widely from region to region, making international coordination difficult. Added to that, the technology’s reputation still suffers from its early association with international criminal activity and, more recently, its environmental credentials have also been called into question. Similar to the technology involved in AI, conventional blockchain technology depends on large, power-hungry infrastructure which raises legitimate concerns about energy use and environmental impact, although it must be noted that more recent developments in the field have significantly reduced the amount of electricity to power an Ethereum-type chain.

In Ireland, there’s the added challenge of slow adoption in the public sector. The Government’s recently revised National Development Plan makes passing reference to AI, but none to blockchain. And while some of the important crypto exchanges like Coinbase and Kraken have an established presence in Dublin, there isn’t a sense that blockchain technology has made an impression on the national psyche just yet. Without a clear strategy at government level, we risk falling behind countries already using the technology to speed up land transactions and improve on the construction workflow. How a more streamlined AI/blockchain approach could improve the delivery of, for example, much needed public housing is an interesting point to consider.

This doesn’t mean we should simply bemoan our misfortune and sit around waiting for the next tech opportunity to come our way. One of the more interesting things about the rise of AI, taken in its broadest sense, is its ability to tackle problems that feel too big or too unwieldy for heavy bureaucracies to sort out. So there’s no reason we couldn’t use AI to help us work through the practical and policy challenges of bringing blockchain into our construction and property systems. If we could get the two technologies working together – AI to design streamlined processes, blockchain to guarantee their integrity – the results could be extremely positive for everyone involved. And the countries that manage to combine AI and blockchain in this way will almost certainly enjoy some real advantages. There’s still an opporutnity for Ireland to put itself out in front – but time is running out.

Blockchain can offer a secure, transparent way to record agreements, and therefore holds potential across construction and property sectors, enabling real-time verification, automating payments, and improving data reliability. Yet its adoption in this context remains limited. In this article, Garry Miley discusses the possible impacts and limitations to the technology’s implementation.

Read

Open House Europe has chosen Future Heritage as its theme for this year.[i] This reframing of “heritage” urges us to consider not only what we have inherited from past generations, but what we would like to pass down to future generations. We are custodians of what we have inherited but we cannot preserve our cities to the point of stagnation. While building for the present, we must also negotiate a relationship to the past and to the future.

In considering the importance of the past and the future in the built environment, it is helpful to first consider the nature of the human relationship to time. This was explored by the philosopher Augustine of Hippo (354–430). In his reflections on the nature of time, Augustine speculates that where the past and the future actually exist is in the mind. The past and the future are present in the mind through memory and expectation, respectively. Augustine refers to this as the distention of the mind.[ii] In the human experience of time, then, the mind is always stretched towards the past through memory, and towards the future through expectation.

In this account, the past only exists through memory. However, memory also extends beyond our minds through the act of inscription. Inscription is described by the philosopher Paul Ricoeur as “external marks adopted as a basis and intermediary for the work of memory”.[iii] These “external marks” are what make up our written and visual histories and cultural narratives; crucially, they also make up our built environment. Our cities act as an intermediary for the work of memory. This is captured by Italo Calvino in his book Invisible Cities:

The city, however, does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows, the bannisters of the steps, the antennae of the lightning rods, the poles of the flags, every segment marked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls.[iv]

Layers of past inhabiting are inscribed in the buildings, streets, and squares of our cities. In our built heritage, we encounter the values and cultural narratives that previously guided the building of our cities. We reinterpret these through the lens of current sociocultural values in a perpetual renegotiation with the past. This is the work of memory.

The relationship to the past, cultivated through this work of memory, is an important aspect of the collective identity of any community. This is the case whether the place is one we have inhabited all our lives or is one that is inscribed with an unfamiliar past. For this reason, built heritage has a powerful role in the sense of identity of the inhabitants of the city. Its loss through war, natural disaster, decay, or development is often met with grief and even outrage.

In this regard, developing a city is a question of considering what memories we consider worth preserving and what future memories we would like to inscribe. The tricky balance of negotiating the relationship between the past and the future in a city can be seen in two late twentieth-century transport-infrastructure-led development projects: one in Amsterdam and one in Dublin.

In the 1970s, the city of Amsterdam’s development plan included the demolition of a large part of the central historic neighbourhood of Nieuwmarkt to make way for the city’s metro. The project proposed to replace the demolished buildings with New-York-style skyscrapers. At around the same time, the Irish transport authority planned to demolish much of the Temple Bar area in Dublin to develop a central bus station and underground rail tunnel. The historic neighbourhoods proposed for the sites of these projects were both in decline and in need of regeneration. The city authorities saw the opportunity this provided for introducing transport infrastructure for the future. A key difference in the circumstances of these projects was that Amsterdam’s had project funding readily available from government and commercial backers; Dublin’s did not.

In Amsterdam, many Nieuwmarkt buildings that had been cleared of their residents in preparation for demolition were occupied by artists and conservationists in an effort to preserve them. However, this local opposition to the demolition did not prevent it from going ahead. Instead, it culminated in some of the city’s worst ever riots, with violent clashes between those who had taken up residence in the district and the police and army sent to forcibly remove them.

Like Nieuwmarkt, Dublin’s Temple Bar area was in need of regeneration as a result of years of decline. However, in this case, funding delays led to the state transport authority letting out the properties it had acquired and earmarked for demolition. The cheap short-term rents attracted artists and small businesses. This brought new life to the area and revealed its potential as a cultural quarter. With intensifying local resistance to the plan and a new civic consciousness of the area’s potential, plans for the bus station were abandoned.

In Dublin, as in Amsterdam, there was a dissonance between the values of those altering the city and the values of those inhabiting the city. However, the delays to the Dublin project sowed the seeds of an alternative approach to the area’s development. Eventually, as part of Dublin’s tenure as European City of Culture in 1991, a competition for the rehabilitative Temple Bar Framework Plan was launched. This was won by Group 91[v] with their plan that proposed preserving much of the existing network of streets, with a handful of interventions including squares, streets, and a few key buildings.

Similarly, in Nieuwmarkt, even though a large number of buildings were demolished and the metro was built, plans for a motorway and tall office buildings were abandoned and Nieuwmarkt was ultimately rebuilt on its original street layout. This is notable as memory is not only inscribed in the materiality of the city, but also in its layout and design. In his book The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard points out that “over and beyond our memories [our formative space] is physically inscribed in us. It is a group of organic habits”.[vi] Memory is inscribed in our cities, and the space of our cities is in turn inscribed in us through choreographing our habits of use.[vii]

Learning from past instances is valuable in deciding how to develop our future heritage and recognising what values are driving our decisions. It is evident from the above examples that changes to a city should be approached with care and follow the “principles of cooperation, equity, and democracy”[viii] that underpin much of Europe’s recent history. A good guiding principle to making interventions in the city that create inclusive socially responsible future heritage is perhaps the generosity of spirit invoked by Grafton Architects' concept of “freespace”.[ix] This includes generosity to current inhabitants through collaboration and the promotion of agency and belonging, and generosity to future inhabitants, particularly by taking measures to mitigate climate change and to make our cities inhabitable in the future.

Like the mind in Augustine’s account of time, the city is stretched towards both the past and the future. Our own values determine how we approach our relationship to the past and what we desire for current and future inhabitants. Where the future exists as expectation in the mind, it exists as possibility in the built environment. The past is present in the built heritage of a site and the future is present in the possibilities that the site presents. In deciding how to alter our urban spaces we are renegotiating our relationship to our past and drawing out the city we want future generations to inherit.

In this article, Dr Sally J. Faulder, referencing this year's Open House Europe theme of "Future Heritage", considers how we ascribe value to our inherited and inhabited built fabric, and to the built heritage we seek to pass on.

Read

OUTSIDE: IN, which ran from 29 May to 20 June, was a display of the work from the UCD School of Architecture Planning and Environmental Planning. This year, the summer exhibition wanted to invite the public into our studio spaces at Richview, continuing an important conversation between architectural education and the wider professional community, sparked by the Building Change project and highlighted at the RDS Architecture and Building Expo last October. The exhibition aimed to invite the outside into our world of Richview architecture and exhibit how the next generation of UCD architects are being prepared to shape the built environment.

The exhibition draws on the ideals of the new Building Change curriculum that has been introduced into the B.Arch over the past three years, and aims to comment on the environmental, social, and economic challenges and opportunities arising in current architectural discourse. OUTSIDE:IN sought to bridge the gap between academia, industry, practice, and policy. It represented a space where the values of architectural education intersect with the realities of contemporary practice.

Featuring the work of seventy-five Master of Architecture students, the work was curated around four forward-looking Design-Research Studios, each tackling real-world challenges through the lens of climate action:

• Housing & the City – rethinking urban living and community development.

• Material Embodiment & Resources – exploring sustainable materials, construction, and structure.

• Landscape Economy & Town – investigating settlement and production through social and economic perspectives.

• Past, Future & Reuse – advancing circularity and adaptive reuse in architecture.

As well as a celebration of the students work, the opening evening began with an insightful panel discussion with panellists Ana Betancour (Urban + Architecture Agency), Lucy Jones (Antipas Jones Architects), Sarah Jane Pisciotti (Sisk Group), Emmett Scanlon (Irish Architecture Foundation) and Conor Sreenan (State Architect, Office of Public Works). The panellists were carefully selected to reflect the diverse paths which are open to us as we leave the four walls of our institution. Although panellists share a common foundation in education and practice, each has pursued different and inspiring trajectories across the architectural realm.

The panel discussion allowed us to consider and reflect on our five years of education and growth, within and outside of the studios in Richview. The overall message was of encouragement, to have confidence, be brave, be unforgiving, unrealistic, and open-minded. The variation in the panellists showed the diverse and varied opportunities and interests that can stem from an architectural education. Our education is about the fundamental ability to evaluate things, understanding our own morals, social values, interests and to ask what can architecture be? Lucy Jones described architecture as a connective tissue that sits between art, policy, developers, education, the city, and people. The field mitigates between the pragmatism of society and the desire to evoke creativity and feeling within the urban environment. As Sarah Jane Piscotti said it is “a desire to know how others think and understand their perspective”. Having seen the process from within, we know there is so much more thought, passion, values, morals, and ideas in a project that can ever be represented on two grey boards. In Richview, we create a culture of curiosity and aim to understand others and we hope to bring this forward in whatever form it may manifest.

OUTSIDE:IN has allowed Richview to open its doors and studios to friends, family and the general public. Emmet Scanlon spoke about a need to de-silo architecture and its educational institutions, making it more accessible to people not within the field. There were certainly moments throughout our education where this sort of ‘wall’ was obvious to us. There was a continuous use of inaccessible language to communicate something that may have seemed relatively simple. At times it felt as if the words were being used to throw us off intentionally. But looking back these moments also taught us to question how and why we communicate our designs in a certain way and, in particular, who we are communicating it to. Despite the challenges and hurdles, our education pushed us to critically think, to find clarity among complex situations, and to constantly strive for inclusivity within our work. It’s a reminder that architecture is not just about what’s built, but about the people, language, and connections we are creating. As we move forward, we now have the opportunity to carry these lessons with us, to make the field more transparent and approachable and to always design with intention and accessibility at the centre.

The Building Change initiative aims to bring climate literacy and sustainability into practice through developing the undergraduate curriculum. A three-year project across all architectural schools in Ireland, it encourages students to engage with and consider the climate emergency, and their impact and responsibility as architects in relation to this. To celebrate the end of the three-year programme in UCD, the Building Change Student Curators held a competition titled, ‘Making Visible the invisible’. The aim of the competition was to submit a piece of work that communicates the often unseen factors that inform design. We cannot always see air, sound, force, energy, waste, biodiversity, environmental impacts etc., yet being able to understand and visualise these systems is a vital part of architectural practice. Similarly, Building Change was often an unseen system, changing and informing education in Richview over the past three years. To celebrate this and bring light to all the innovative and positive impacts the initiative had, a collaged mural was erected in the front foyer representing Building Change’s timeline within the school, plotted in relation to wider environmental changes on a global scale. The timeline is a visual representation indicating how our education is adapting and responding to the climate emergency.

OUTSIDE: IN opened Richview’s studio doors to the public, showcasing how UCD’s architecture students are responding to today’s environmental, social, and economic challenges. This article explores how the exhibition, grounded in the Building Change initiative, reflects a shift in architectural education connecting academia, industry, and community through design, dialogue, and climate action.

ReadWebsite by Good as Gold.