"Streets and their sidewalks, the main public spaces of a city, are its most vital organs. Think of a city and what comes to mind? Its streets."

— Jane Jacobs [1]

If you watch any Discover Ireland ad, you’ll probably see the image of some woolle- jumper-wearing musician singing on the street, their empty guitar case in front of them half full of change. The lively street full of people and music is the hallmark of how an Irish city is perceived. For some, when musicians and other performing artists take to the streets they can be an annoyance, but for most, they act as welcome entertainment. Streets like Grafton Street in Dublin and Shop Street in Galway have accepted the culture of busking and this art has become a real asset to the street and the city; art that can take place on any street and on any corner. To be an ideal busking location the street needs: a good amount of footfall; room for people to stand and listen; and for the musician and the crowd not to be interfering with the pedestrians going about their day. This article discusses two streets, one where the architecture of the city space works for buskers and the other against them.

The streets discussed are O'Connell Street in Limerick city and Blackfriars Street in Waterford city. For both of the locations, I will compare busking during the Christmas period, and so the streets were busy with people. The weather was cold but not wet and, when I passed by the musicians, a decent number of people stopped to listen. With relatively similar situations, this article discusses how the architecture of the street influenced the relative success of the busk.

On O’Connell Street, Limerick city, a duo were playing their hearts out to the shoppers who had gathered around for some passing entertainment. Even though this was the widest section of footpath along the street, a bottleneck of pedestrians soon developed. The performers were huddled back as close to the windows of the display behind them as to minimise their impact on this traffic jam. At this point on the street, there was a group of people waiting for the traffic lights to change in their favour, shoppers making their way into the department store, a queue of commuters waiting for the bus, and the audience gathered around the musicians. An ill-placed rubbish bin narrowed the route further. This footpath was trying to do too much even before the buskers arrived. The pair were undoubtedly talented, and I’m sure their time on the street was well worth their while, but the architecture of this street was not working in their favour.

In Waterford city, Blackfriars Street connects John Roberts Square to City Square Shopping Centre. On this narrow street outside the now empty shop front of P. Larkin’s (a butcher that stopped selling meat in 1983), a band of four musicians were playing. This four-piece took up much more space on the street than the aforementioned duo while causing less of an impact on the route of the Christmas shoppers. Being a pedestrianised street, the people passing by had plenty of space to stop and listen without feeling like they were in the way of others. People could pause and take a minute to listen to one or two songs before emptying the contents of their coin wallets and carrying on with their day. This simple generosity of space afforded to pedestrians meant the street became much more than just a route between two popular retail spots. Instead, it allowed a few hopeful young musicians to improve the atmosphere of this corner of the city. Even the closed shop behind the buskers played its part in this successful performance, its shop front framing the musicians in the same way as a stage.

I am not suggesting O’Connell Street hardly works or that Blackfriars Street is working particularly hard solely on their ability to accommodate busking, but rather our streets have many secondary uses and the different ways people use a street and feel comfortable using a street is what makes them places of value. The streets of our cities are at their best when a musician is able to use the doorway as their stage and the passing public feel at ease enough to stop and enjoy the performance.

Working Hard / Hardly Working is supported by the Arts Council through the Architecture Project Award Round 2 2022.

[1] Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Modern Library ed. New York: Modern Library, 1993.

Scale in street-making is often a function of the objects or beings that a street serves, and a product of the time when it was designed and built. The medieval urban street would be narrow and tight if considered in the context of the width of a modern car - it was self-evidently designed for human-only occupation. Wide urban streets are a post-industrial phenomenon, but facilitating trade was not the only cause of expansion: for instance, the importance of the Dame Street-to-Dublin Castle route in 18th Century Dublin was emphasised by employing a wide-street design.1 Similarly, width was considered a vehicle for improving air quality and circulation, such as with Haussmann’s 19th century re-design of some of Paris’s most well-known avenues.2

The process of making new spaces, including urban streets, usually begins with a shopping list of needs and requirements which mix together to inform and produce a space of sufficient scale to balance a wide range of competing interests. Urban fabric generally thrives on the variety of scales and spaces produced by this process, which helps to ground the occupier in a sense of time and place. A number of Irish examples of wide streets, however, exist with a poor or at least muddled sense of human occupation.

Pearse Street is one such example. Originally named Great Brunswick Street, the street is a product of industrial expansion in the Dublin Docklands during the 18th century, and was renamed after Padraig Pearse in 1924. Its creation revitalised an area “hidden from the city by the bulk of T.C.D,” 3 and its width is an echo of the legal scale prescribed by the Wide Streets Commission in the Act of 1758, even though it was never an original target. It was, put simply, an urban trade route from the delivery point to final destination.

It is approximately 1.2 kilometers in length, spanning from Ringsend Road and the Grand Canal Bridge to the East, linking up with Tara Street and College Green to the West. At 19 metres wide, it is less than half that of O’Connell Street (49 metres). It consists of four lanes of one-way west-bound traffic flanked by two relatively narrow footpaths. It has few trees, central electricity poles or other vertical delineation, and mostly consists of low, slow-moving traffic and a high-level transversal Dart Bridge appearing at an angle from the upper storeys of the Naughton Institute of Trinity College. Walking it feels like hard work, with little to no changes in its surface materiality, landscaping or any other kind of visual variety to retain a wanderer’s interest along their way.

Much of the southern end constitutes the perimeter of Trinity College, with relatively little life at the street level, while the northern end is peppered with a number of vacant and closed off facades. It is telling that such a prominent street and transport node, with the benefit of south-facing facades, seemingly turns its back on the pedestrian. The root of the issue likely stems from an unpleasant and dangerous atmosphere created by the cacophony of traffic, but the removal of traffic in and of itself is not conducive to a successful street. It begs questions about what interventions can be done to reinvigorate this seemingly forgotten stretch?

Modern interventions to wide streets generally consist of two actions. Firstly, they can be subdivided with hardscaping and landscaping in an attempt to sequentially arrange the street occupation nicely for the human: if we move through a wide street like a series of mini streets and spaces, our interactions with the street will be easier; our understanding will be broken down and more easily digested.

O’Connell Street is one such example that has benefitted from spatial, visual and material compartmentalisation. The tarmac which is applied to the majority of the roadway is interrupted at the GPO, where a high-quality granite paving sett is used for both the road and footpath, emphasising the importance of that historic building and providing variety for the pedestrian. The width of the roadway is punctuated by a central pedestrian spine throughout, with all three pedestrian thoroughfares on the street organised around a variety of trees, old and young.

The success of such segregation would point toward a logic that streets designed for pedestrians should therefore be similarly organised. Such an approach, however, may diminish the original grandeur and scale of the street. It can prompt wayfinding issues by interfering with the visibility of landmarks that contribute to a sense of place inherent to a city’s fabric.4

The second option is generally to leave them to their original devices; the accommodation of vehicular movement. In an era where movement is dominated by the car, and the streets’ spaces are merely vehicular lanes, this makes for an element of the urban fabric, which is unfriendly and, frankly, unoccupiable.

“First we shape cities, then they shape us.” 5 Pearse Street was – finally - recently the subject of a Dublin City Council decision to restructure traffic routes, with the removal of cars approaching from Westland Row. This, hopefully, is the conclusion of the previous indifference it has suffered from - now that space for cars has been diminished, human-centred urban interventions, with a particular emphasis on variety in all aspects, should follow suit.

In this article, Laoise McGrath reflects on the challenges presented by wide streets, the prioritisation of cars over people, and the potential for more inclusive urban environments.

Read

Buried deep underground, encased in two and a half meters of concrete foundation is a copper scroll. A map of the night sky is engraved on its durable surface accompanied by the following declaration in five languages; English, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and Chinese:

“This building began on the 22nd day of November 1960 A.D. according to the Gregorian calendar. The planets in the heavens were as shown on this celestial map. The universal language of astronomy will permit men forever to understand and know this date.” [1]

Replete with hubris and utopian optimism, Bertrand Goldberg, architect of Chicago's “Marina City” dreamt of a monument that would not only change the future of residential architecture but whose legacy may outlive its own material longevity. Forty floors above this map, overlooking the Chicago River, is my one bedroom apartment. However lofty Goldberg's ambitions, they did succeed in reshaping how many people live today, ushering in a new era of high rise living.

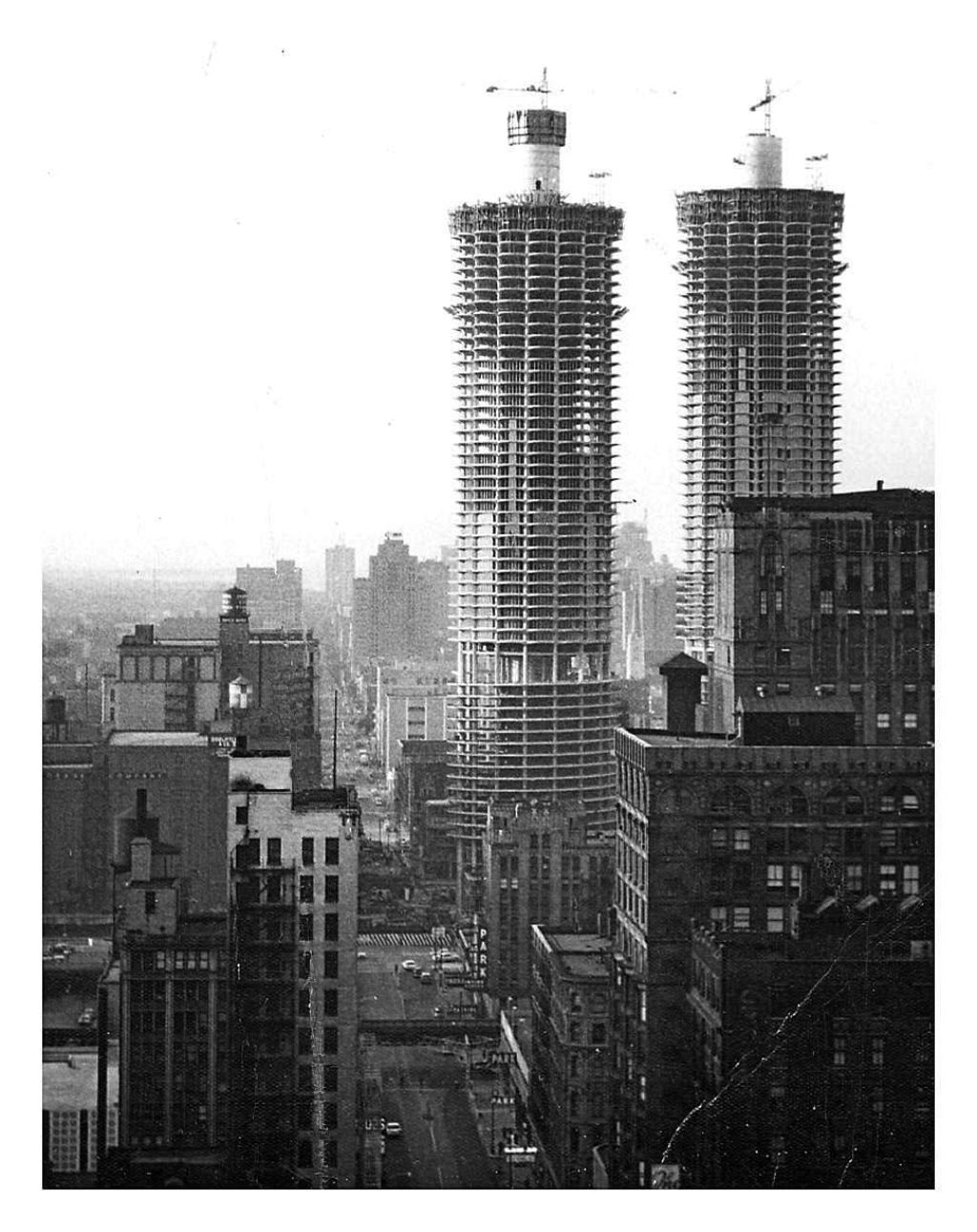

Marina City was the most ambitious residential project ever constructed in Chicago, crucially funded by Building Service Employees International Union seeking to reverse decades of “white flight”, the mass migration of white people from urban areas to post-war suburbs. Societal change, rather than profit incentives, was the primary driver of the project, and a radical solution to city living was required to sway public opinion in the immediate, and long term.

Conceived as a city within a city, the mixed-use complex accommodated a range of amenities including restaurants, a theatre, a bowling alley, and an office building within two 65 storey towers housing 1400 people, the tallest residential buildings in the world at the time of its completion in 1968. [2] Although dwarfed by some of its newer neighbours, they stand more than double the height of Dublin's tallest building at 179 meters, and are just shy of the Poolbeg Chimneys. As the first major mixed use complex in the USA, it inspired a boom of inner city construction that aspired to compete with the ease and amenities of the suburbs.

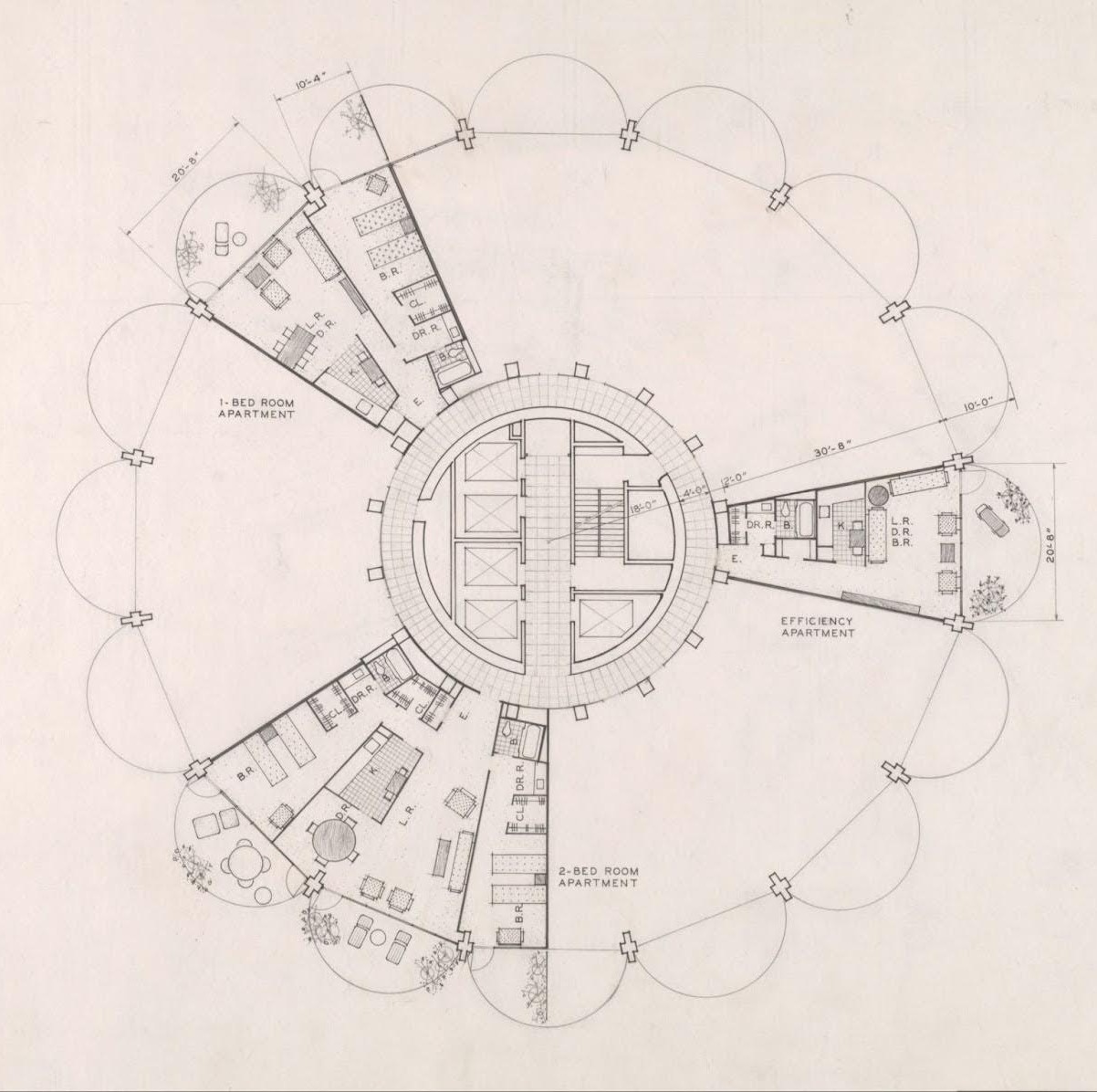

Right angles dominate Chicago; its unrelenting grid plan stretches for hundreds of square miles, and Marina City was a radical departure from the existing urban fabric. Once a student of Mies Van der Rohe, Goldberg broke from the rigid modernity of his former mentor, inspired by natural organic forms. The two towers share identical circular plans, rising from a spiralling base of open parking and topped with forty residential storeys. Each apartment radiates from the central core like a petal, culminating in a rounded balcony, giving the buildings their iconic flower shaped plan.

Creating lasting buildings also requires cultural sustainability, and the most sustainable structures are those that are appreciated. Marina City was immediately embraced by Chicagoans, becoming adored civic and mass media icons dubbed the “corn cob” towers. The towers appear tectonically simple yet sculpturally complex; a monolithic cast in-situ concrete frame with steel framed glazing slotted between, separating inside and out.

The structure holds the interior space, massive beams stem from the circular core, delineating living spaces. They sweep towards the floor at the building's edge forming columns, then arc into cantilever balconies in a display of structural grandiosity rarely seen in residential architecture. Completely rejecting Corbusier's free-plan, where structural elements can be completely freed from interior arrangements, here space and structure are in complete harmony.

Within this rigid frame is the flexibility to adapt to changing living standards. In our apartment, the antiquated enclosed kitchen has been opened up creating a single living space. The bathroom was enlarged and the black vinyl asbestos containing floor was replaced with a warmer hardwood. At 72m2, the comfortable apartment exceeds the minimum requirement for one bedroom apartments in Ireland by 60%, its irregular plan opening up to the strangely distant metropolis forty floors beneath. Neither sky nor ground are visible from inside, the city looms above and disappears from view below.

Residences are raised above 19 floors of parking – an unavoidable reality of 1960s America – and as the first major development in a declining industrial area, lifting the residential blocks may have given some relief from the smog and dust below. This conversely embodied a kind of “anti-urban” philosophy where multiple levels of parking dominate and “eyes on the street” are non-existent. The “city within a city” mantra perhaps becomes an island within a city. Despite its achievements, Marina City’s anti-pedestrian urban edge with moat-like level changes and large car ramps, removes any sort of meaningful presence at street level to non residents.

Although the area now bustles with restaurants, bars and apartments, it is far from atypical residential neighbourhood. Flanked on three sides by streets that have more in common with the M50 than most urban environments; six lanes of constant traffic, window rattling subwoofers and illegal drag racing and are common late night nuisances.

Connection between residents can also feel strangely isolating. Elevators are not conducive to forming relationships and the curving plan allows for interaction between neighbouring balconies but doesn't encourage either. These large balconies feel like an interpretation of the traditional American porch lifted into the sky, shaded relief from the summer sun, or sheltered hideout to watch colossal lightning storms roll over the great plains and crash into Lake Michigan. They also allow you to engage in the longstanding American tradition of watching your neighbours from the porch.

Looking across to the adjacent tower, presumably people are enjoying their balconies, but they are lost against the infrastructural scale of the complex. Voices drift across, a party far above, arguing below. If you look closely enough they start to emerge. A TV flickers on, they're watching Friends, “Brian” from the local bar waves over as he's brushing his teeth on his balcony, a couple shut their blinds after drinking a bottle of wine on the balcony. Like L.B Jeffries looking out his rear window, I wonder if I am the only one piecing these disparate stories together. The feeling is one of shared isolation rather than community, alone together high above the chaotic streets below.

That is not to say there is no community here. A thriving residents group exists if you decide to partake. Movie nights occur weekly, taking place on the roof deck in the summer months. Art talks, game nights and seasonal parties regularly fill the shared amenity space.

Irish perceptions of community are more parochial; passing neighbours at the front door, greeting the postman. While traditional domestic formations may be useful facilitators for chance encounters, it is naive to imagine that communities require a specific type of urban form to propagate. Communities are formed by longevity and security. Apartments here are privately owned or leased long term, but beyond that, residents are fiercely proud of their iconic modernist home. The ambition of drawing people back to the urban center was achieved by creating liveable homes. Many residents have been here for decades, some from its very inception.

Despite the abundance of new construction in Ireland, the race to the bottom of minimum standards and the prevalence of build-to-rent schemes prevents apartment living being seen as a viable long term option. The corporatisation of housing provides neither the long term security nor exemplary housing needed to form community or societal change.

Similar to the Irish housing crisis, urban dereliction in Chicago was an immediate problem that needed a swift response. The architects and – crucially – an ambitious funder, understood that an exemplary project was needed to shift societal attitudes, not a short term band-aid. Marina City stands as a testament that radical solutions can significantly alter public opinion and trajectory of an urban area. This kind of thinking is urgently required, and if we must look up and abroad for solutions, then let us ponder on the porches of Marina City.

In this article Dónal O’Cionnfhaolaidh reflects on high rise living, community, and the legacy of an architectural icon after four years of living in America's most ambitious residential project.

Read

Dancing at the crossroads and bothántaíocht, visiting neighbours; sharing news, music and lore were very much a part of Irish life not so long ago. Reliance on social interaction held a higher importance to people back then than it does today. Face to face interaction is becoming less and less of an occurrence, while interaction is still happening, only now, through our screens.

What does this mean for our public spaces? The way in which we occupy space has changed. Is this the reason that many of these public spaces scattered across our island aren't working as well as they could or once did? Or is it that we don’t value our public spaces like other European cities do? Is it the lack of marble sculptures and terrazzo tiled squares or the sunnier skies?

Despite the ever changing micro-climates in the west of Ireland, there are public spaces in towns, and villages that have important social spaces at the centre of their civic arrangements. Simultaneously, these towns have ample exterior spaces that are struggling to find their identity.

In the South West of Ireland, on the Dingle Peninsula, within the Gaeltacht of Chorca Dhuibhne, lies a small fishing town with a patchwork of coloured townhouses. The town follows the natural contours of land and sits steadily against the rising slope overlooking the bay. Dingle town, known and visited by many, is characterised by its cultural richness which is celebrated and shared through festivals and community events.

The town's openness and social personality creates a level of pressure on its public spaces to perform; these places have a certain responsibility to engage communities and enhance performance. In Dingle, there are three public spaces that interest me, each for varying reasons: An Díseart; a series of garden rooms, the Town Park - a struggling pocket longing to find its place at the heart of the town - and lastly the Mart, a vital gathering place for the agricultural community along with being a trading center.

I know these spaces well having grown up on the peninsula yet it's only now I find myself considering them differently, conducting a sort of analysis.

On Green Street within the grounds of St Mary's Church and the neo-gothic former convent, lies a series of garden rooms, each with their own personality. One enters through a gate within an opening in a stone wall, adjacent to the church and from there you are lead up and around winding paths, experiencing the circular patterns of the ground, mini mazes, a greenhouse, wild flowers, a willow tunnel, stone walls, the nuns graveyard guarded by two angel statues at the gate and enclosed by white iron railings, native trees planted by local families, places of rest, more in some rooms than others. It's an old stone wall that continuously wraps around these gardens that encloses the public space, while also providing protection for the plants on this wind swept peninsula.

This is a public space which is welcoming to all, enjoyed by many, respected by its visitors, and cared for by the community. A place of adaptability, having various events taking place here throughout the year; the sounds of ceol tradisiúnta coming from the wooden gazebo during the summer months, taispeántais ealaíne from local artists within the greenhouse or immersed within the gardens during Féile na Bealtaine or Other Voices and locals improving their planting skills through gardening courses during the off season months. To me it is a place that holds a certain sense of serenity, calmness, but most of all it's a place I feel I can connect with physically and mentally, a nurtured space for everyone.

Only a short stroll down Green street and down Greys Lane is another one of the town's public spaces. Looking back at the 1841 OS Map of the town, it is clear where the park derived from, simply the back of many of the townhouses which then formed a large green open space in the centre.

Dingle's Town Park, despite the many attempts to reinvigorate this space for the town, its people and its visitor unfortunately remains somewhat of a struggling space. Nestled within the town's core centre its location is quite fortunate for an Irish town park. Its only entrance is located almost at the corner of where Greys Lane meets Dykegate Lane, the home of the Art Deco Facade of the Phoenix Cinema. The park doesn’t reveal itself at its entrance. Through a set of green metal gates one enters and then follows a hardened tarmacked path up to the right through what feels like an alleyway which then widens out to a large open space. A concrete paved path wraps around the perimeter, while more hard surfaced areas occupy the centre of the park, one tennis/basketball court enclosed by metal fencing and a smaller area, also enclosed by metal fencing which once housed a children's playground, now taken away. Green grassed areas take up the rest of the space with some trees and some scattered benches. This is a place that has been associated with antisocial behaviour, due to its impermeability.

I spent some time analysing the park with help of the creative minds of the 2023-2024 Transition year students in Pobalscoil Chorca Dhuibhne while taking part in the Irish Architecture Foundation's Architects in Schools programme. Together with the local students new designs and interventions were developed through drawings, discussions and model making to enhance and improve what could be the future of the park.

Interesting ideas included adding a second entrance through the historical wall at Orchard Lane at the north eastern side. Dingle was once a walled town and this stretch of stone wall is the remnants that once enclosed the town. Creating an entrance here could be a way to celebrate the historic wall while giving it a new life and providing a functional access route from one side of the town to the other. This could become part of the daily routes taken by the town users. Other interventions equally as interesting and important focused on the recreational aspect; market stalls, sports zones, children's play areas, and practical elements; seating, lighting, security while other students emphasized redesigning the layout of the park. These are all elements that would add to the place allowing one to connect with it in one way or another.

The Dingle Mart is a cornerstone of rural life on the Peninsula, combining its practical function as a livestock trading center with its cultural role as a community gathering point. Its multifunctional setting, which consists of a large open hard surfaced area and the mart building itself which contains the teared ring room where the selling happens, a canteen and shed space toward the rear with pens for the animals. The large open space outside occupies a carpark for most of the time and then on Saturdays the mart place, a tradition that has been taking place for many years and is a vital part of the lives of so many who live on the peninsula and in many Irish towns across the country. The mart is host to the sale of sheep and cattle usually, but once a year events like The Scotch Ram judging and Agricultural Show take place.

Benjamin Gault (1858 - 1942) was an American conservationist and ornithologist, who captured vital moments of life in Dingle and its surrounding while visiting the west of Ireland in the mid 1920’s, circa 100 years ago. This footage was only recently found with the help of a local farmer, Micheál Ó Mainnín from Baile an Fheirtéaraigh. I find it fascinating to use these images to compare how these spaces were once occupied and used compared to today.

Each space described belongs to Dingle town and are a part of the town's fabric, they each serve a separate purpose. They are places of social interaction, where people connect with public space. I think that perhaps these spaces should work together and integrate with their surrounding context to provide flow throughout the town. I think as architects there is a need to listen to locals more closely, at the end of the day, they are the ones who know these spaces and places the best, they are the users of the space.

We have to look to the future of the town and think how these exterior rooms can be an integral part of the town's system, pockets of public space which enhance the towns sociality, cad atá i ndán dóibh, what future do these spaces hold? As Dingle continues to evolve, preserving these spaces is crucial. Public spaces like these deserve our attention and respect, for they form the backbone of the community.

These spaces are inherently different, spaces of leisure and trade don't seem connected at first, but they are the cores of this town, without them Dingle loses all character, all space to breathe. They are not just physical locations but embodiments of the town’s spirit, reflecting its history, culture, and resilience. In the face of changing times, Dingle’s public spaces remind us of the importance of thoughtful design and shared stewardship. Whether through festivals in the park, quiet reflection in the Díseart gardens, or the enduring traditions of the Mart, these spaces connect the past with the present, ensuring that Dingle remains a vibrant hub for generations to come.

Tara Nic Gearailt reflects on how changing social habits affect our use of public space. Focusing on Dingle, she highlights the need to preserve and adapt shared spaces to sustain community life.

ReadWebsite by Good as Gold.