In Donnybrook, an inner suburb of Dublin, the studio complex of Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcaster, is dominated by five buildings that exemplify late modern architecture in Ireland. The masterplan for their strictly rectilinear combinations of concrete, steel, and glass was laid out by the architect Ronnie Tallon in 1960, following which Scott Tallon Walker (STW) designed the various buildings in the subsequent twenty years. When first opened, they were celebrated for their cutting-edge aesthetics and engineering, combining functionality and beauty on an integrated campus that advertised Ireland’s modernity [1]. Today the buildings are under-appreciated, though they were added to the Register of Protected Structures (RPS) in 2019 [2].

Recent controversy has once again put a spotlight on the future of RTÉ, including its campus architecture. Twelve months on, the organisation may now be recovering, with a ‘New Direction’ strategic plan and several reports on its governance and finances providing a roadmap for reform [3]. The Irish government provided the national broadcaster with €56m of emergency funding in November 2023, but this is a small fraction of RTÉ’s needs. It has a long way to go to persuade a doubtful public and politicians of its sustainability, and future funding has been made contingent on organisational changes that may or may not work, including a 20% reduction in the broadcaster’s workforce, a redistribution of some activity to smaller studios in Limerick and Cork, and increased outsourcing of its productions to independent companies.

Though downplaying it, the strategic report keeps open the possibility of a partial or total sale of RTÉ’s studios to improve the company’s finances and its corporate size and shape. It calls for “a streamlined RTÉ … operating on a smaller footprint within the Donnybrook site and with more modern facilities that require less maintenance … enable modern working and production practices and meet regulations, compliance requirements and sustainability targets”. It admits that “relocating RTÉ off the current Donnybrook site … does not appear to be economically viable” but it remains open to “exploring options for the vacated areas or land sale”. Politicians and independent media producers have often asked if we might ‘lift and shift’ RTÉ’s headquarters to a less prominent location, and in 2017 RTÉ sold 8.64 acres of its Donnybrook site for €107m as a temporary solution to its long-running cashflow crisis. Its latest plan notes that its remaining 24 acres are currently valued at only €100m due to challenging conditions in commercial real estate and the addition of RTÉ’s most important buildings to the RPS, but the possibility is left open that a higher price might be achieved in the future.

Of course, in a capitalist economy, most properties are disposable, and our built environment rapidly changes. Nonetheless, further sale of RTÉ’s lands would be a bad idea. Its Donnybrook base is not only a group of world-class buildings but an internationally important centre of cultural production. Elsewhere, similar studios are accepted for their specialised engineering, their need for frequent capital investment, and their skilled workforce that cannot be easily replaced. Some major studios have been repurposed – for example, the recent conversion to apartments of the former BBC Television Centre in London’s Shepherd’s Bush. But the BBC has been under siege from private media conglomerates and frequently hostile governments for forty years. In other cities, especially in the EU, public service broadcasters have kept studios running, modernising in situ, sometimes with nearby additions. Hence, the longevity of the Maison de la Radio in Paris, the RBB Television Centre in Berlin, and the Via Teulada studios of RAI in Rome, all originating in the 1930s-60s and transformed for the digital age.

Even in Los Angeles, the famous CBS Television City, designed by William Pereira, continues to grow in studio buildings first opened in 1952, while Sony, Fox, and Paramount operate studios that were founded in the 1910s and 1920s, with many of the original buildings still in use today. Los Angeles has less prominent public service media and more property speculation than most cities, but its studios remain central – economically, culturally, and geographically – while modernising, densifying, and diversifying. Unfortunately, RTÉ has been caught in an unproductive financial tug of war in which citizens and public representatives praise its work but question its value for money. Competing private sector media companies naturally call for the state broadcaster to be restructured. However, the international history of studios should encourage us to protect not only RTÉ’s buildings but its Donnybrook site as a whole – an invaluable concentration of talent, expertise, equipment, and services that is in prime metropolitan real estate for good reason.

The economic geographer Allen J. Scott highlights the distinctive ‘clustering’ of media industries around dense networks of specialised facilities, skilled workers, and suppliers that are often unique in a given region or country. Scott’s influential analysis of Hollywood emphasises the long-term benefits of integrating media industries in large cities – as does the recent PwC report The Role of the BBC in Creative Clusters (2022) [4]. Relocating RTÉ would run counter to their findings, dispersing a cluster instead of consolidating it. In Ireland, we have relocated large public facilities – moving UCD to Belfield in the 1960s, moving TU Dublin to Grangegorman – but those moves centralised disparate units. Efforts to decentralise – for example, government departments – have proven much more controversial. The high value of RTÉ’s estate is sometimes cited to argue for its sale, but this misunderstands the industry. Media studios are not like other manufacturers for whom large amounts of mass-produced inventory account for much of their total value. RTÉ’s physical estate makes up a greater proportion of its worth because the commodities it produces are relatively small, unique, and transient: digital images and sound, not objects made of metal, plastic, or timber.

Several film and television studios now operate outside of Dublin – Ardmore Studios in Wicklow, Troy Studios in Limerick, Titanic Studios in Belfast – and new studio construction has been having a moment worldwide, driven by demand for new product from streaming media services, government incentives, and institutional investors looking for new opportunities at a time when other kinds of commercial real estate are in difficulty. But reports suggest the trend may be slowing; the most recent new studio planned for Ireland – Hackman Capital Partners’ Greystones Media Campus – has been delayed by the recent actors’ and writers’ strike in Hollywood [5]. So new studio construction does not always go smoothly. And all of these are private sector companies mostly making movies or television dramas, often for overseas clients, frequently subject to seasonal or economic fluctuations in activity and not heavily involved in broadcasting, news gathering, or live entertainment – so not directly comparable with a public service broadcaster like RTÉ.

RTÉ did have an ambitious investment plan for Donnybrook, Project 2025, but it was shelved during the financial crisis circa 2010 [6]. It would have provided a large integrated multi-functional studio facility with state-of-the-art technology, greater floorspace and production capacity, and a better environmental rating. However, shockingly, it would have required demolition of most of STW’s original buildings which, it was claimed, could not be modernised or upgraded to the standards required by digital media – an unconvincing claim given comparable developments in other countries (eventually RTÉ did manage a relatively modest but effective upgrade of its Studio 3 building for television news in 2019). A substantial revision of the Project 2025 plan now could strike a better balance between innovation and preservation while serving the needs of RTÉ and the Irish public. Reduction or closure of the site should be ruled out, and the studio buildings should be renewed. Though still photogenic, they are not in good condition. RTÉ’s small but elegant modernist canteen was closed several times last year by rat infestations and its other buildings also need repair. This costs money but would give the country a flagship media facility of enduring value.

To this end, RTÉ would do well to make its Donnybrook site more approachable, and this might aid the company’s PR. Studios are usually secure and secluded from the public – to protect their intellectual property, for the privacy of celebrities, and to encourage a sense of mystery and audience anticipation. Nevertheless, comparable studios run popular studio tours, on-site physical archives, and performance venues. Some of these were anticipated by Project 2025. Adding them now – as well as, say, a museum and educational centre – could enhance public understanding of RTÉ, improve media literacy, and protect RTÉ’s campus and buildings for successive generations to enjoy. Ancillary benefits might include independent media companies leasing some of RTÉ’s site but maintaining the media cluster, and improved pedestrian street life between Donnybrook village and UCD, which have densified over the years. Relevant international comparisons suggest we should double down on RTÉ’s Donnybrook site rather than reduce or vacate it.

This would also serve environmental priorities. It is increasingly recognised that the ecological cost of growth is often high. To ‘lift and shift’ RTÉ to a new location, rather than update and expand its current facilities, would consume a lot of building materials and energy while disrupting supply routes and workers’ commutes, increasing RTÉ’s carbon footprint. This would contradict its sustainability goals, which include a 50% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030. Since Project 2025 was launched, the tide of international opinion has turned against demolition, as adaptive reuse initiatives such as House Europe and the New European Bauhaus demonstrate [7]. RTÉ’s sustainability goals could be better achieved by maximising its options in situ. Another way the state might do this would be to buy back the portion of RTÉ’s campus that was sold to a private company for residential development. The state often buys land for strategic infrastructure, and the land that was sold has been idle since 2017. That sale was first proposed in 2002 at the height of the Celtic Tiger property boom and it would arguably never have happened if RTÉ had been properly funded in the first place. Instead, its revenue shortfalls, which have now been constant for twenty years, were a function of neoliberal trends towards deregulation and privatisation that have since come in for scrutiny in Ireland and worldwide. We now have a chance to address these for the good of our media and built environment alike. Even Tánaiste Micheál Martin recently opined that RTÉ should not rush into further land sales because “very often selling land is something you will regret later” [8]. This is not to argue for a state monopoly – Ireland needs a thriving, diverse, creative, and entrepreneurial media sector. But it also needs vibrant public service media anchored in vibrant public places.

Open Space is supported by the Arts Council through the Arts Grant Funding Award 2024.

1. RTÉ Archives online, ‘International Delegation Visits Montrose’ (1962) and ‘Donnybrook, RTÉ’s New Home’ (1963). Available at: https://www.rte.ie/archives/2017/0524/877565-international-tv-engineers-visit-rte-studios/ and https://www.rte.ie/archives/2017/1213/927116-new-rte-campus/ (accessed: 27 June 2024).

2. RTÉ Archives online, ‘RTÉ Buildings’. Available at: https://www.rte.ie/news/ireland/2019/0403/1040530-rte-buildings/ (accessed: 27 June 2024). RTÉ’s campus was smaller than University College Dublin at nearby Belfield but similar in style and density. The two sites have developed differently but should be equally recognised as Irish versions of treasured masterpieces like Mies van der Rohe’s Illinois Institute of Technology (1942-56), the Edificio Copan (1952-66) by Oscar Niemeyer in São Paulo, or the UNESCO Headquarters (1953-58) in Paris by Pier Luigi Nervi, Marcel Breuer, and Bernard Zehrfuss. For an appreciation of the architecture of UCD, see F. O’Kane and E. Rowley, Making Belfield: Space + Place at UCD, University College Dublin Press, 2020.

3. RTÉ, A new direction for RTÉ. Available at: https://www.rte.ie/documents/eile/2023/11/a-new-direction-for-rte-14-11-23.pdf (accessed: 27 June 2024). On 25 June 2024, RTÉ released a new, more detailed version of the New Direction plan, though the substance remains the same: https://www.rte.ie/documents/eile/2024/06/rte-strategy-new-direction-2025-2029.pdf. It was announced on the same date that RTÉ plans to remove production of its flagship shows Fair City and The Late Late Show from the Donnybrook studios, to have them produced elsewhere. My analysis leads me to question the wisdom of such a move.

4. A. J. Scott, On Hollywood: The Place, the Industry, Princeton University Press, 2005; Pricewaterhouse Coopers, The role of the BBC in creative clusters: Analysing the BBC’s wider impact on the UK economy, November 2022.

5. T. Galvin, ‘Wicklow TD John Brady quizzes Finance Minister over two-year delay to €300m Greystones Media Campus’, Irish Independent, 18 June 2024. Available at: https://www.independent.ie/regionals/wicklow/bray-news/wicklow-td-john-brady-quizzes-finance-minister-over-two-year-delay-to-300m-greystones-media-campus/a1960620893.html (accessed: 27 June 2024).

6. STW Architects, ‘Project 2025’ [website]. Available at: https://www.stwarchitects.com/our-work/archive/rte-2025/ (accessed: 27 June 2024).

7. House Europe, [website]. Available at: https://www.houseeurope.eu/ (accessed: 27 June 2024); New European Bauhaus, [website]. Available at: https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/index_en (accessed: 27 June 2024).

8. H. McGee, E. Malone, D. Raleigh, V. Clarke, ‘Taoiseach says RTÉ will not be put under pressure to sell Montrose site’, The Irish Times, 14 September 2023.

All photographs copyright © Mark Shiel/MediaUrbanism, 2024.

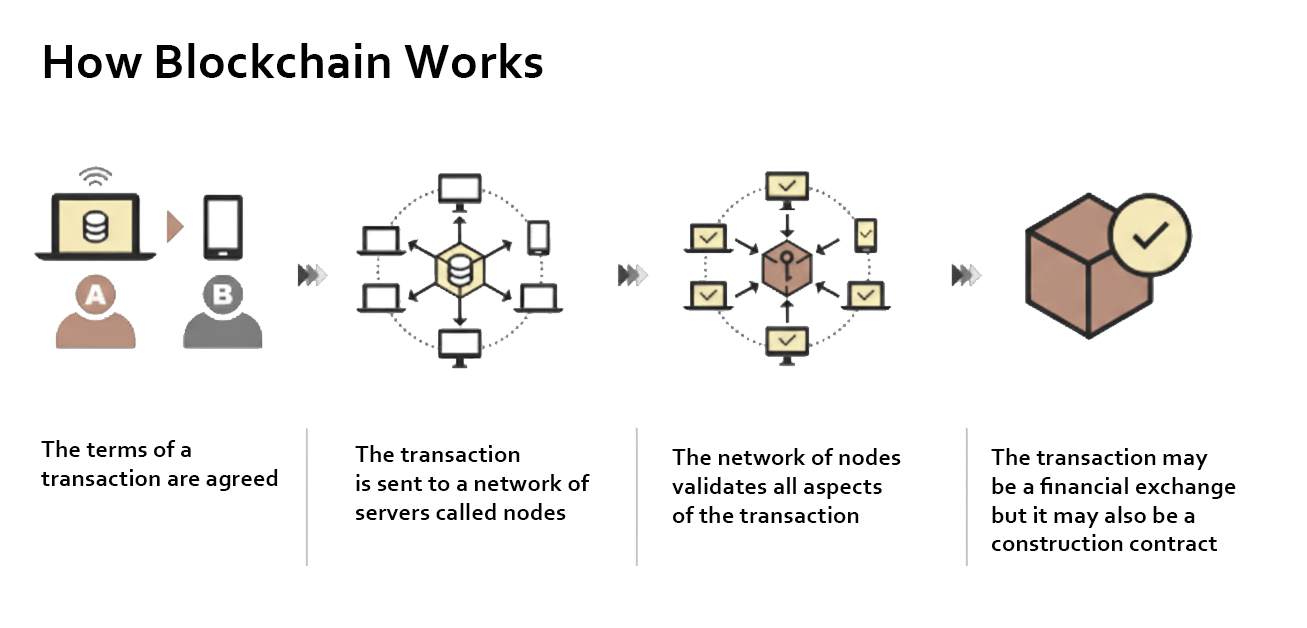

Most people call it crypto but for the purposes of this exercise we’ll use the term "blockchain".

At its core, a blockchain is simply a way of recording an event on a digital ledger instead of in a paper document. This could, for example, be a record of an agreement - the kind of agreement people have been making between one another for as long as agreements have existed. If you do X, I’ll do Y. In the past, we’d make the agreement official by signing some papers in a solicitor’s office. However, with a smart contract running on a blockchain we take a different approach: first, we set out all the conditions that have to be met before the contract can be entered into; then, instead of asking a solicitor to decide when these conditions have been met, we write the whole thing in computer code and let technology act as the referee. The terms of the agreement are implemented without fuss and in a way that’s difficult to undo. If I suddenly get cold feet about some commitment I may have made, I can’t wriggle free of my obligations by finding loopholes and stirring up trouble. That’s the first interesting thing about a typical smart contract: terms and conditions are fairly hard wired.

The second interesting thing about blockchain contracts is the way details of the agreement are stored. Once the computer confirms that all the conditions have been met, the record isn’t just dumped onto one big central server which would be an obvious target for hackers. Instead, a copy of the entire record is kept on many different computers (nodes) spread out around the world. Each copy is kept in a series of linked “blocks” and each block contains a sort of digital fingerprint of all the verified information on which it is based. If someone tries to change even the tiniest detail in one block, the fingerprints won’t match and the change will be rejected. For extra security, large files (a good example for our purposes would be contract drawings) can be stored separately using a system like IPFS. The main block can be primed to keep an eye on these files to make sure that important material hasn’t been tampered with.

It didn’t take long for the earliest blockchain experimenters to see how this new technology could work as a form of money. Money, after all, is just another type of agreement. And so, around 2009, the terms "Bitcoin" and crypto entered the public imagination. Almost immediately, Bitcoin became synonymous with dodgy financial dealings and the internet was soon full of stories about international criminal gangs getting around banking regulations by paying each other in this new invisible currency.

But if we ignore all the hyperbole and look again at what an Ethereum-type blockchain involves – a system that has the same secure, tamper-proof data blocks as Bitcoin but also supports smart contracts – you can see how it might be used for things far beyond dodgy money. Anything that needs a secure, verifiable agreement could benefit from a blockchain approach, including many of the processes that underpin building and construction.

One of the more interesting examples so far of the use of blockchain in the broader construction/real estate space has been in property transactions and land registration. Anyone who’s ever bought a house, no matter where, will know that the process is slow, bureaucratic, paper-heavy and prone to error. Blockchain offers a secure, transparent alternative. In recent years Georgia (the country, not the US state), Dubai, Sweden and other jurisdictions have been testing out blockchain systems to record transfer of title. Media reports suggest the trials have been generally successful with transactions being completed sometimes in a matter of minutes.

In construction, the potential is just as easy to imagine. Take the example of a contractor completing the installation of a complicated foundation on a new project. Instead of waiting weeks for manual inspections to take place, on-site sensors confirm in real time that the work meets the agreed technical specification. That verification is automatically logged on a blockchain, which triggers immediate payment. Large companies like Skanska and Bechtel have been experimenting with these and similar approaches for quite some time, tracking materials from their source to their final installation as well as checking authenticity and compliance.

Another interesting area for potential blockchain crossover is the use of BIM. In a big public building project the architect, engineers and contractors might each start out working on the same 3D BIM model. But as the job progresses, each consultant makes one tweak here and another one there and soon various "official" versions of the same model have come into existence. When a dispute eventually erupts over whether a particular detail was formally approved, no one can be sure whose version of the detail is the “real” one.

With a blockchain-based approach, each approved version of the BIM model could be time-stamped and stored in a tamper-proof way so that a clear, verifiable record of what was agreed can be referred to. We could take this concept one step further and link the approved building model to a city’s digital twin – say, Dublin or Cork – with the building’s latest data slotted straight into the digital city model. This would mean that planners, utility providers and emergency services would have a reliable, up-to-date digital version of the building to work from. And, in fact, this is something that is already being explored in Dublin where the City Council’s partnership with DCU on creating a digital twin has received favourable coverage in the trade press.

While there has been progress in these and other areas, particularly in the private/commercial sphere, wide-scale adoption of blockchain technology in the worldwide construction industry faces a number of hurdles. For a start, regulations vary widely from region to region, making international coordination difficult. Added to that, the technology’s reputation still suffers from its early association with international criminal activity and, more recently, its environmental credentials have also been called into question. Similar to the technology involved in AI, conventional blockchain technology depends on large, power-hungry infrastructure which raises legitimate concerns about energy use and environmental impact, although it must be noted that more recent developments in the field have significantly reduced the amount of electricity to power an Ethereum-type chain.

In Ireland, there’s the added challenge of slow adoption in the public sector. The Government’s recently revised National Development Plan makes passing reference to AI, but none to blockchain. And while some of the important crypto exchanges like Coinbase and Kraken have an established presence in Dublin, there isn’t a sense that blockchain technology has made an impression on the national psyche just yet. Without a clear strategy at government level, we risk falling behind countries already using the technology to speed up land transactions and improve on the construction workflow. How a more streamlined AI/blockchain approach could improve the delivery of, for example, much needed public housing is an interesting point to consider.

This doesn’t mean we should simply bemoan our misfortune and sit around waiting for the next tech opportunity to come our way. One of the more interesting things about the rise of AI, taken in its broadest sense, is its ability to tackle problems that feel too big or too unwieldy for heavy bureaucracies to sort out. So there’s no reason we couldn’t use AI to help us work through the practical and policy challenges of bringing blockchain into our construction and property systems. If we could get the two technologies working together – AI to design streamlined processes, blockchain to guarantee their integrity – the results could be extremely positive for everyone involved. And the countries that manage to combine AI and blockchain in this way will almost certainly enjoy some real advantages. There’s still an opporutnity for Ireland to put itself out in front – but time is running out.

Blockchain can offer a secure, transparent way to record agreements, and therefore holds potential across construction and property sectors, enabling real-time verification, automating payments, and improving data reliability. Yet its adoption in this context remains limited. In this article, Garry Miley discusses the possible impacts and limitations to the technology’s implementation.

Read

Open House Europe has chosen Future Heritage as its theme for this year.[i] This reframing of “heritage” urges us to consider not only what we have inherited from past generations, but what we would like to pass down to future generations. We are custodians of what we have inherited but we cannot preserve our cities to the point of stagnation. While building for the present, we must also negotiate a relationship to the past and to the future.

In considering the importance of the past and the future in the built environment, it is helpful to first consider the nature of the human relationship to time. This was explored by the philosopher Augustine of Hippo (354–430). In his reflections on the nature of time, Augustine speculates that where the past and the future actually exist is in the mind. The past and the future are present in the mind through memory and expectation, respectively. Augustine refers to this as the distention of the mind.[ii] In the human experience of time, then, the mind is always stretched towards the past through memory, and towards the future through expectation.

In this account, the past only exists through memory. However, memory also extends beyond our minds through the act of inscription. Inscription is described by the philosopher Paul Ricoeur as “external marks adopted as a basis and intermediary for the work of memory”.[iii] These “external marks” are what make up our written and visual histories and cultural narratives; crucially, they also make up our built environment. Our cities act as an intermediary for the work of memory. This is captured by Italo Calvino in his book Invisible Cities:

The city, however, does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows, the bannisters of the steps, the antennae of the lightning rods, the poles of the flags, every segment marked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls.[iv]

Layers of past inhabiting are inscribed in the buildings, streets, and squares of our cities. In our built heritage, we encounter the values and cultural narratives that previously guided the building of our cities. We reinterpret these through the lens of current sociocultural values in a perpetual renegotiation with the past. This is the work of memory.

The relationship to the past, cultivated through this work of memory, is an important aspect of the collective identity of any community. This is the case whether the place is one we have inhabited all our lives or is one that is inscribed with an unfamiliar past. For this reason, built heritage has a powerful role in the sense of identity of the inhabitants of the city. Its loss through war, natural disaster, decay, or development is often met with grief and even outrage.

In this regard, developing a city is a question of considering what memories we consider worth preserving and what future memories we would like to inscribe. The tricky balance of negotiating the relationship between the past and the future in a city can be seen in two late twentieth-century transport-infrastructure-led development projects: one in Amsterdam and one in Dublin.

In the 1970s, the city of Amsterdam’s development plan included the demolition of a large part of the central historic neighbourhood of Nieuwmarkt to make way for the city’s metro. The project proposed to replace the demolished buildings with New-York-style skyscrapers. At around the same time, the Irish transport authority planned to demolish much of the Temple Bar area in Dublin to develop a central bus station and underground rail tunnel. The historic neighbourhoods proposed for the sites of these projects were both in decline and in need of regeneration. The city authorities saw the opportunity this provided for introducing transport infrastructure for the future. A key difference in the circumstances of these projects was that Amsterdam’s had project funding readily available from government and commercial backers; Dublin’s did not.

In Amsterdam, many Nieuwmarkt buildings that had been cleared of their residents in preparation for demolition were occupied by artists and conservationists in an effort to preserve them. However, this local opposition to the demolition did not prevent it from going ahead. Instead, it culminated in some of the city’s worst ever riots, with violent clashes between those who had taken up residence in the district and the police and army sent to forcibly remove them.

Like Nieuwmarkt, Dublin’s Temple Bar area was in need of regeneration as a result of years of decline. However, in this case, funding delays led to the state transport authority letting out the properties it had acquired and earmarked for demolition. The cheap short-term rents attracted artists and small businesses. This brought new life to the area and revealed its potential as a cultural quarter. With intensifying local resistance to the plan and a new civic consciousness of the area’s potential, plans for the bus station were abandoned.

In Dublin, as in Amsterdam, there was a dissonance between the values of those altering the city and the values of those inhabiting the city. However, the delays to the Dublin project sowed the seeds of an alternative approach to the area’s development. Eventually, as part of Dublin’s tenure as European City of Culture in 1991, a competition for the rehabilitative Temple Bar Framework Plan was launched. This was won by Group 91[v] with their plan that proposed preserving much of the existing network of streets, with a handful of interventions including squares, streets, and a few key buildings.

Similarly, in Nieuwmarkt, even though a large number of buildings were demolished and the metro was built, plans for a motorway and tall office buildings were abandoned and Nieuwmarkt was ultimately rebuilt on its original street layout. This is notable as memory is not only inscribed in the materiality of the city, but also in its layout and design. In his book The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard points out that “over and beyond our memories [our formative space] is physically inscribed in us. It is a group of organic habits”.[vi] Memory is inscribed in our cities, and the space of our cities is in turn inscribed in us through choreographing our habits of use.[vii]

Learning from past instances is valuable in deciding how to develop our future heritage and recognising what values are driving our decisions. It is evident from the above examples that changes to a city should be approached with care and follow the “principles of cooperation, equity, and democracy”[viii] that underpin much of Europe’s recent history. A good guiding principle to making interventions in the city that create inclusive socially responsible future heritage is perhaps the generosity of spirit invoked by Grafton Architects' concept of “freespace”.[ix] This includes generosity to current inhabitants through collaboration and the promotion of agency and belonging, and generosity to future inhabitants, particularly by taking measures to mitigate climate change and to make our cities inhabitable in the future.

Like the mind in Augustine’s account of time, the city is stretched towards both the past and the future. Our own values determine how we approach our relationship to the past and what we desire for current and future inhabitants. Where the future exists as expectation in the mind, it exists as possibility in the built environment. The past is present in the built heritage of a site and the future is present in the possibilities that the site presents. In deciding how to alter our urban spaces we are renegotiating our relationship to our past and drawing out the city we want future generations to inherit.

In this article, Dr Sally J. Faulder, referencing this year's Open House Europe theme of "Future Heritage", considers how we ascribe value to our inherited and inhabited built fabric, and to the built heritage we seek to pass on.

Read

OUTSIDE: IN, which ran from 29 May to 20 June, was a display of the work from the UCD School of Architecture Planning and Environmental Planning. This year, the summer exhibition wanted to invite the public into our studio spaces at Richview, continuing an important conversation between architectural education and the wider professional community, sparked by the Building Change project and highlighted at the RDS Architecture and Building Expo last October. The exhibition aimed to invite the outside into our world of Richview architecture and exhibit how the next generation of UCD architects are being prepared to shape the built environment.

The exhibition draws on the ideals of the new Building Change curriculum that has been introduced into the B.Arch over the past three years, and aims to comment on the environmental, social, and economic challenges and opportunities arising in current architectural discourse. OUTSIDE:IN sought to bridge the gap between academia, industry, practice, and policy. It represented a space where the values of architectural education intersect with the realities of contemporary practice.

Featuring the work of seventy-five Master of Architecture students, the work was curated around four forward-looking Design-Research Studios, each tackling real-world challenges through the lens of climate action:

• Housing & the City – rethinking urban living and community development.

• Material Embodiment & Resources – exploring sustainable materials, construction, and structure.

• Landscape Economy & Town – investigating settlement and production through social and economic perspectives.

• Past, Future & Reuse – advancing circularity and adaptive reuse in architecture.

As well as a celebration of the students work, the opening evening began with an insightful panel discussion with panellists Ana Betancour (Urban + Architecture Agency), Lucy Jones (Antipas Jones Architects), Sarah Jane Pisciotti (Sisk Group), Emmett Scanlon (Irish Architecture Foundation) and Conor Sreenan (State Architect, Office of Public Works). The panellists were carefully selected to reflect the diverse paths which are open to us as we leave the four walls of our institution. Although panellists share a common foundation in education and practice, each has pursued different and inspiring trajectories across the architectural realm.

The panel discussion allowed us to consider and reflect on our five years of education and growth, within and outside of the studios in Richview. The overall message was of encouragement, to have confidence, be brave, be unforgiving, unrealistic, and open-minded. The variation in the panellists showed the diverse and varied opportunities and interests that can stem from an architectural education. Our education is about the fundamental ability to evaluate things, understanding our own morals, social values, interests and to ask what can architecture be? Lucy Jones described architecture as a connective tissue that sits between art, policy, developers, education, the city, and people. The field mitigates between the pragmatism of society and the desire to evoke creativity and feeling within the urban environment. As Sarah Jane Piscotti said it is “a desire to know how others think and understand their perspective”. Having seen the process from within, we know there is so much more thought, passion, values, morals, and ideas in a project that can ever be represented on two grey boards. In Richview, we create a culture of curiosity and aim to understand others and we hope to bring this forward in whatever form it may manifest.

OUTSIDE:IN has allowed Richview to open its doors and studios to friends, family and the general public. Emmet Scanlon spoke about a need to de-silo architecture and its educational institutions, making it more accessible to people not within the field. There were certainly moments throughout our education where this sort of ‘wall’ was obvious to us. There was a continuous use of inaccessible language to communicate something that may have seemed relatively simple. At times it felt as if the words were being used to throw us off intentionally. But looking back these moments also taught us to question how and why we communicate our designs in a certain way and, in particular, who we are communicating it to. Despite the challenges and hurdles, our education pushed us to critically think, to find clarity among complex situations, and to constantly strive for inclusivity within our work. It’s a reminder that architecture is not just about what’s built, but about the people, language, and connections we are creating. As we move forward, we now have the opportunity to carry these lessons with us, to make the field more transparent and approachable and to always design with intention and accessibility at the centre.

The Building Change initiative aims to bring climate literacy and sustainability into practice through developing the undergraduate curriculum. A three-year project across all architectural schools in Ireland, it encourages students to engage with and consider the climate emergency, and their impact and responsibility as architects in relation to this. To celebrate the end of the three-year programme in UCD, the Building Change Student Curators held a competition titled, ‘Making Visible the invisible’. The aim of the competition was to submit a piece of work that communicates the often unseen factors that inform design. We cannot always see air, sound, force, energy, waste, biodiversity, environmental impacts etc., yet being able to understand and visualise these systems is a vital part of architectural practice. Similarly, Building Change was often an unseen system, changing and informing education in Richview over the past three years. To celebrate this and bring light to all the innovative and positive impacts the initiative had, a collaged mural was erected in the front foyer representing Building Change’s timeline within the school, plotted in relation to wider environmental changes on a global scale. The timeline is a visual representation indicating how our education is adapting and responding to the climate emergency.

OUTSIDE: IN opened Richview’s studio doors to the public, showcasing how UCD’s architecture students are responding to today’s environmental, social, and economic challenges. This article explores how the exhibition, grounded in the Building Change initiative, reflects a shift in architectural education connecting academia, industry, and community through design, dialogue, and climate action.

ReadWebsite by Good as Gold.