“The first queer spaces of the modern era were the dark alleys, unlit corners, and hidden rooms that queers found in the city itself. It was a space that could not be seen, had no contours, and never endured beyond the sexual act. Its order was and is that of gestures.”[1]

The two spaces which will be compared in this essay are the cruising routes in Phoenix Park, and the Boilerhouse, a gay sauna located in Dublin city. Both of these spaces are used for engaging in public or semi-public sexual encounters, providing a level of privacy and anonymity, while also exposing the cruiser to a group of people also seeking sexual encounters. It is between this duality of secrecy and community where these spaces are most interesting architecturally, and both spaces deal with these issues in unique ways.

The cruising routes of Phoenix Park are a leftover from historically queer spaces, where cities could provide invisible infrastructure that was simultaneously in plain view and hidden through a number of coded signals. Less widespread now, as queerness in Ireland has become more socially accepted, these routes have developed out of necessity; a need to queer existing city infrastructure to provide space for same-sex sexual encounters. These spaces were undefined architecturally but would often emerge with some shared characteristics. Parks in particular often offered all of the requirements for a thriving cruising culture to develop. Aaron Betsky defines four characteristics of cruising spaces. Firstly, it needs “conditions that in and of themselves dissolve walls and other constraints”; meaning that outdoor cruising typically takes place at night. Second, it needs a labyrinthine quality, deterring the use of the space for functions other than sex, and providing “multiple barriers to intervention or observation”. Third, that cruising takes place where the city breaks down, at its edge as a whole, or at the edges of buildings in the “stoops, porticos, windows and doorways”. Fourth, “cruising grounds have to parallel, but not be the same as, the public spaces of the city”, existing within the same space physically but separated by cultural differences and differing requirements of its occupants.

These routes have developed throughout Dublin city, and while many have faded out of use as the city changes, some remain active. In Phoenix Park, a popular cruising location has developed a community of men who often require anonymity. These cruisers might not be able to engage in same sex sexual activities at home, or might find gay saunas such as the Boilerhouse too prominent within the city centre. One cruiser, Peter, scribed the appeal of the cruising spot at Phoenix Park: “Gay men have this fascination of walking around because they're constantly on the hunt for something better – you know? – and they don't particularly like to stand still. They don't. So the park – that area of the park – is quite ideal because you've got lots of different trails and different routes that you can take.”[2]

Spatially, it conforms to all of Betsky’s characteristics of cruising spaces, though these are not always consistent. Peter describes how during winter many of the spots usually sheltered by leaves become much more visible, and that during rainy days some areas on sloped ground become too slippery to use. In these cases, people might have sex in a car park, or around the edge of an old sports changing room. In this way, the cruising spot is more transient, and changes even within yearly cycles and with the weather.

By contrast, the Boilerhouse remains mostly consistent, and despite being too prominent for some gay men, still engages with privacy and protection. Located on a quiet lane in Temple Bar, the front entrance is unassuming, with a nondescript sign and a foyer after the main door where you can wait before being buzzed in by an attendant in a small kiosk. The unassuming facade conceals the sexually liberated interior, where queer sexuality is allowed to be freed from social norms. Unlike the fully public cruising spaces in the city and in Phoenix Park, the Boilerhouse was designed specifically to be a space for sex a formalised version of traditional cruising, it mirrors the characteristics as described by Betsky. As with other shops and establishments, it is a private space which acts as an extension of the city when open and provides a semi-public environment where its patrons can cruise with more security and enclosure than in outdoor cruising routes. The bathhouse provides spaces to wander, to gather, and more reclusive rooms and cubicles to retreat into. In the Boilerhouse these areas are obviously defined; after the changing rooms and lockers, the ground floor is open with a bar in a large double-height space, visible from the walkways on the second floor. On each floor above, the spaces become more and more compartmentalised, offering varying levels of privacy and enclosure.

The building maintains its semi-public condition throughout, even in the more enclosed areas. Partition walls often don’t meet the floor, and mirrors above stall doors provide a level of engagement with the more open spaces of the building. Glory holes offer connections between rooms or cubicles and further blur the lines between private and semi-public space. This arrangement provides a level of community not found in the Phoenix Park, where communication between cruisers is limited, and often reduced to subtle signals or codes. In the Boilerhouse, communication is not about identifying other cruisers but conveying more nuanced sexual preferences or interest in a particular partner.

While the Boilerhouse and other saunas might be understood as a natural progression from cruising in public spaces, it remains inaccessible to some as a private establishment with opening hours, entry fees, and door policies. These spaces both represent physical manifestations of queer space. They are defined by sex, and while queer architectural theory has developed beyond synonymising queerness with homosexuality, it provides an insight into the development of queer culture and its place in the development of the city. These queer spaces for sex disrupt a traditional way of viewing public space, and the gradations of privacy typically understood, where sexual activities happen in the privacy of home. Public space within the city is nuanced, and not so easily defined when considering its multitude of users, and so an understanding of queer people’s existence within the city is imperative for its development.

Working Hard / Hardly Working is supported by the Arts Council through the Architecture Project Award Round 2 2022.

1. A. Betsky, Queer Space, Architecture and Same-Sex Desire, New York, William Morrow & Company, 1997.

2. Anonymous (Peter), interviewed by Nicolas Howden, 29 November 2022.

3. G. Chauncey, ‘Privacy Could Only Be Had in Public: Gay Uses of the Streets’, in Stud: Architecture of Masculinity, J. Sanders (ed.), New York, Princeton Architectural Press, 1996, p. 224.

Nestled behind the Crocknamurrin Mountain Bog, beyond the sublime of the Glengesh Pass, lies the town of Ardara (Ard an Rátha), a rural village in southwest Donegal with a population of about 750 people. The context of southwest Donegal, like much of the West of Ireland, is characterised by a harsh environment shaped by the Atlantic coastline and its famed remoteness - factors that have long contributed to the allure and longevity of its most renowned export industry: Donegal Tweed.

In the spirit of the series, this article looks not towards whether a place is working hard or hardly working, but instead towards what we might glean from turning our attention to spaces of work themselves; what they might tell us about the story of a place, of how an emergent rural town found itself at the heart of a thriving cottage industry, and how that legacy continues to shape the fabric of this place today.

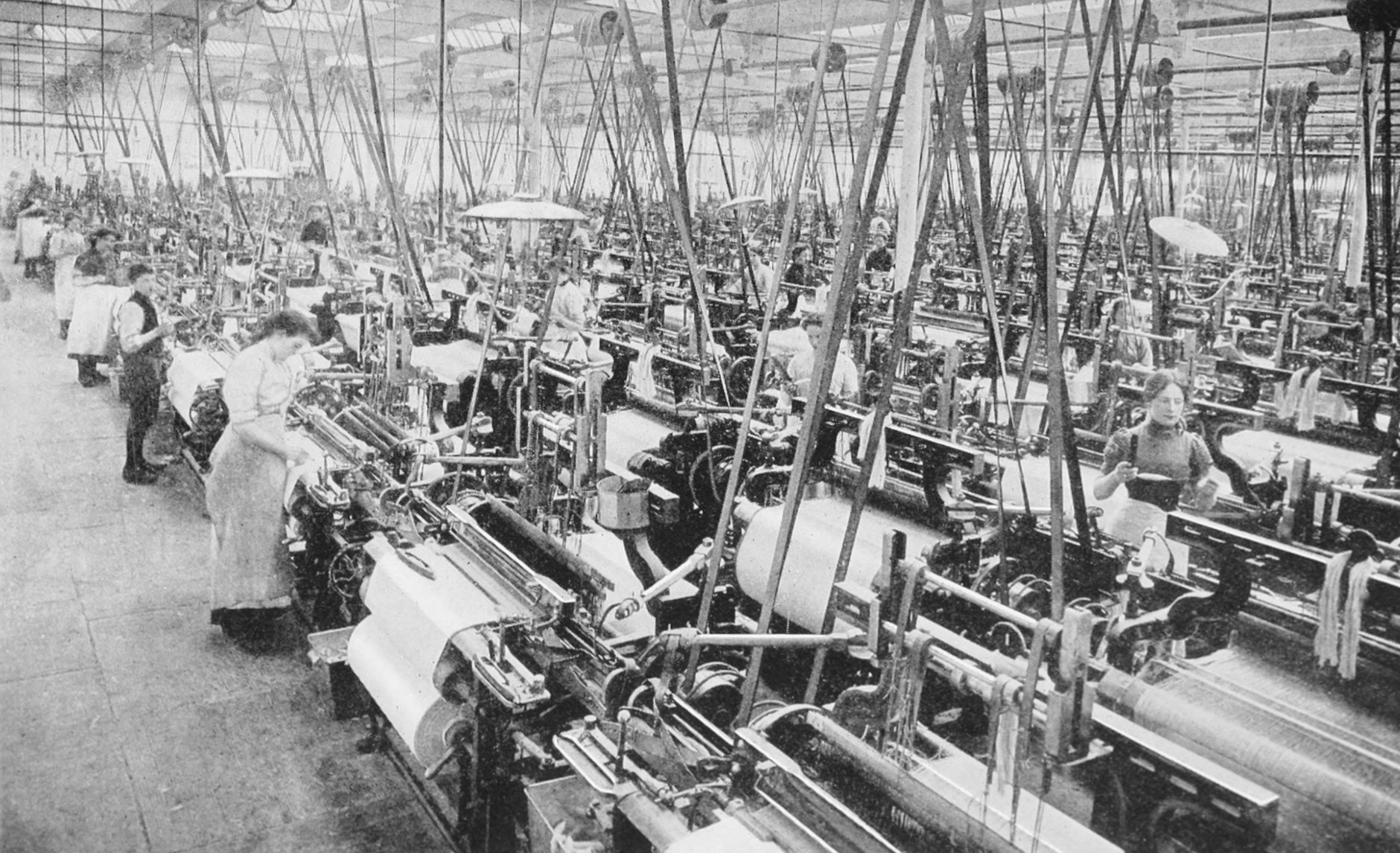

Anecdotal accounts refer to the sounds of working looms echoing through Ardara’s streets, where a trained ear could identify who exactly was weaving by the distinctive and unique clatter of their shuttle. A trade sustained by cottage industry into the 1970’s, looms were typically kept in working weaving sheds independent from the house – an early iteration of working from home before the concept of WFH as we have since come to know it. Separate from or to the rear of someone’s home, space for weaving has long been understood as a working shed more so than a studio space, or a place for artistic expression.

An informal environment, the weaving shed is carefully shaped by and for its user, with maximum practicality and ease of production in mind. What presents at first a disorderly chaos of timber sections, scrap yarns and curious tools reveals, on further interrogation, a perfectly planned and functional ecosystem. Level access is optimal for transferring heavy beams and yarns; garage doors to a laneway accommodate the proportions of double-width warp beams, and their loading in and out of trailers; 2.4m clear height allows vertical movement of the jacks, while 3.5m in width is required for swinging of the sley; a single LED light fixture plugged loosely into an extension cable illuminates the cloth beam for intricate on-loom mending, and so on. Beneath the tangible disarray of objects worn and used is something intangible – behaviours, habits and knowledge passed down through generations, linking this intimate, private space and its geographical location on earth inherently and forever to the identity of a craft. Workshop spaces like these belie the story and success of a place in ways both material and immaterial.

Geographically, the challenging conditions of mountainous bog terrain engendered a sense of isolation that contributed to the preservation of these traditional craft techniques. This terrain also provided the natural materials and resources required to produce and dye handwoven woollen textiles in times when communities were largely self-reliant, and living off the land.

In an economic context, Ardara’s textile industry has experienced periodic success punctuated by significant challenges. The Wool Act of 1699 implemented by the British Parliament prohibited, during a time of great success in the European market, the export of Irish woollen goods beyond the UK, to protect the English wool trade from competition with growing, colonial markets.

Ardara’s textile industry was supported by initiatives implemented by the Congested Districts Board, established by Arthur James Balfour at the end of the 19th Century with the intention of “killing Home Rule with kindness”. It is said that a visit paid by him to Donegal, prior to his establishment of the Board, “first opened his eyes to the poverty and misery prevailing there and brought about a change of heart” [1]

The Congested Districts Board's initiatives were designed to support local production and provide employment to areas that historically had relied on agriculture and home-based crafts. For Ardara, this took the form of the introduction of stamping high-quality handwoven goods, and led to the construction of a Mart building in 1912, where weavers would traverse from all over the rural area with their homespun frieze for inspection, storage and sale to the global market. [2]

The Congested Districts Board was purportedly involved in the provision of an improved hand-loom for weaving, invented by Mr. W.J.D. Walker, the Board’s organiser and inspector for industries, who generously placed his invention at the disposal of the Board. These improved looms were then supplied to the local weavers on a loan installment system.

Although it was arguably established to consolidate British influence in the region, it cannot be denied that the Congested Districts Board aided in supporting this cottage industry at a time where it was in decline and uniquely, in establishing a network between towns in southwest Donegal; linked by the spinning factory in Kilcar, to a carpet factory in Killybegs, to Magee’s in Donegal Town, to the handweavers and Mart of Ardara and its surrounds. Whether intentionally or not, this network has enabled not only the craft to endure in harsh climates - meteorological and economical - but also, the make-up of these places, how they interact with one another, and what is literally woven into their urban and rural fabric.

Often when looking at public space or the development of towns and their successes, with an architectural lens we look to the physical - how trade, culture, or industry have physically shaped a place. In this instance, to begin to understand this place, it is necessary to observe how these same cultural influences have shaped a town in an immaterial, intangible, maybe even invisible way. The weaving shed as it has always existed, is a fragment of industry previous; a byproduct of its environment, natural resources and the resourcefulness of the people who inhabited it and sustained a craft.

In Teague’s pub you’ll find pillow cases handwoven by John Heena leaning against the snug at the front, and a beautiful shuttle placed above the door that once belonged to the owner’s grandfather. Ask anyone in the town and they will likely know something or have some connection to weaving, be it an old loom in their shed, or some lingering knowledge of how to construct parts of a loom. This almost inherent shared knowledge and understanding provides a mystical reminder of the vibrancy and prevalence of a once commonplace skill.

Across Ireland we have seen a surge in the value of craft, of people returning to making things from scratch, growing foods from the earth, using their hands to create, all in response - and sometimes protest - to the mass production, consumption and colossal waste that is draining our planet’s resources. Following the introduction of power looms in the 1970’s, the industry changed, making Donegal Tweed a legitimate and successful export worldwide which continues to thrive today. On a smaller scale, we find ourselves in a different cycle of weaving, where the focus lies on the craft of weaving as an artisanal trade, rather than a scalable business model.

What was introduced earlier in this article as a humble, pragmatic workspace presents itself now as evidence of living heritage, a fragment of an industry past and an emblem of the future of handweaving in Ireland. It prompts a wider reflection on the revitalisation of Irish towns at large, examining their interconnectedness and the intangible forces that bind and sustain them. A holistic, ground-up approach is critical to any and all revitalisation efforts, rooted in the understanding of a place and responsive to the needs of its future; remaining ever mindful to see the story behind the shed.

Ailbhe Beatty explores the relationship between craft, culture, and heritage in Irish towns, examining how workshop spaces reveal the story of a place in ways material and immaterial.

Read

Scale in street-making is often a function of the objects or beings that a street serves, and a product of the time when it was designed and built. The medieval urban street would be narrow and tight if considered in the context of the width of a modern car - it was self-evidently designed for human-only occupation. Wide urban streets are a post-industrial phenomenon, but facilitating trade was not the only cause of expansion: for instance, the importance of the Dame Street-to-Dublin Castle route in 18th Century Dublin was emphasised by employing a wide-street design.1 Similarly, width was considered a vehicle for improving air quality and circulation, such as with Haussmann’s 19th century re-design of some of Paris’s most well-known avenues.2

The process of making new spaces, including urban streets, usually begins with a shopping list of needs and requirements which mix together to inform and produce a space of sufficient scale to balance a wide range of competing interests. Urban fabric generally thrives on the variety of scales and spaces produced by this process, which helps to ground the occupier in a sense of time and place. A number of Irish examples of wide streets, however, exist with a poor or at least muddled sense of human occupation.

Pearse Street is one such example. Originally named Great Brunswick Street, the street is a product of industrial expansion in the Dublin Docklands during the 18th century, and was renamed after Padraig Pearse in 1924. Its creation revitalised an area “hidden from the city by the bulk of T.C.D,” 3 and its width is an echo of the legal scale prescribed by the Wide Streets Commission in the Act of 1758, even though it was never an original target. It was, put simply, an urban trade route from the delivery point to final destination.

It is approximately 1.2 kilometers in length, spanning from Ringsend Road and the Grand Canal Bridge to the East, linking up with Tara Street and College Green to the West. At 19 metres wide, it is less than half that of O’Connell Street (49 metres). It consists of four lanes of one-way west-bound traffic flanked by two relatively narrow footpaths. It has few trees, central electricity poles or other vertical delineation, and mostly consists of low, slow-moving traffic and a high-level transversal Dart Bridge appearing at an angle from the upper storeys of the Naughton Institute of Trinity College. Walking it feels like hard work, with little to no changes in its surface materiality, landscaping or any other kind of visual variety to retain a wanderer’s interest along their way.

Much of the southern end constitutes the perimeter of Trinity College, with relatively little life at the street level, while the northern end is peppered with a number of vacant and closed off facades. It is telling that such a prominent street and transport node, with the benefit of south-facing facades, seemingly turns its back on the pedestrian. The root of the issue likely stems from an unpleasant and dangerous atmosphere created by the cacophony of traffic, but the removal of traffic in and of itself is not conducive to a successful street. It begs questions about what interventions can be done to reinvigorate this seemingly forgotten stretch?

Modern interventions to wide streets generally consist of two actions. Firstly, they can be subdivided with hardscaping and landscaping in an attempt to sequentially arrange the street occupation nicely for the human: if we move through a wide street like a series of mini streets and spaces, our interactions with the street will be easier; our understanding will be broken down and more easily digested.

O’Connell Street is one such example that has benefitted from spatial, visual and material compartmentalisation. The tarmac which is applied to the majority of the roadway is interrupted at the GPO, where a high-quality granite paving sett is used for both the road and footpath, emphasising the importance of that historic building and providing variety for the pedestrian. The width of the roadway is punctuated by a central pedestrian spine throughout, with all three pedestrian thoroughfares on the street organised around a variety of trees, old and young.

The success of such segregation would point toward a logic that streets designed for pedestrians should therefore be similarly organised. Such an approach, however, may diminish the original grandeur and scale of the street. It can prompt wayfinding issues by interfering with the visibility of landmarks that contribute to a sense of place inherent to a city’s fabric.4

The second option is generally to leave them to their original devices; the accommodation of vehicular movement. In an era where movement is dominated by the car, and the streets’ spaces are merely vehicular lanes, this makes for an element of the urban fabric, which is unfriendly and, frankly, unoccupiable.

“First we shape cities, then they shape us.” 5 Pearse Street was – finally - recently the subject of a Dublin City Council decision to restructure traffic routes, with the removal of cars approaching from Westland Row. This, hopefully, is the conclusion of the previous indifference it has suffered from - now that space for cars has been diminished, human-centred urban interventions, with a particular emphasis on variety in all aspects, should follow suit.

In this article, Laoise McGrath reflects on the challenges presented by wide streets, the prioritisation of cars over people, and the potential for more inclusive urban environments.

Read

Buried deep underground, encased in two and a half meters of concrete foundation is a copper scroll. A map of the night sky is engraved on its durable surface accompanied by the following declaration in five languages; English, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and Chinese:

“This building began on the 22nd day of November 1960 A.D. according to the Gregorian calendar. The planets in the heavens were as shown on this celestial map. The universal language of astronomy will permit men forever to understand and know this date.” [1]

Replete with hubris and utopian optimism, Bertrand Goldberg, architect of Chicago's “Marina City” dreamt of a monument that would not only change the future of residential architecture but whose legacy may outlive its own material longevity. Forty floors above this map, overlooking the Chicago River, is my one bedroom apartment. However lofty Goldberg's ambitions, they did succeed in reshaping how many people live today, ushering in a new era of high rise living.

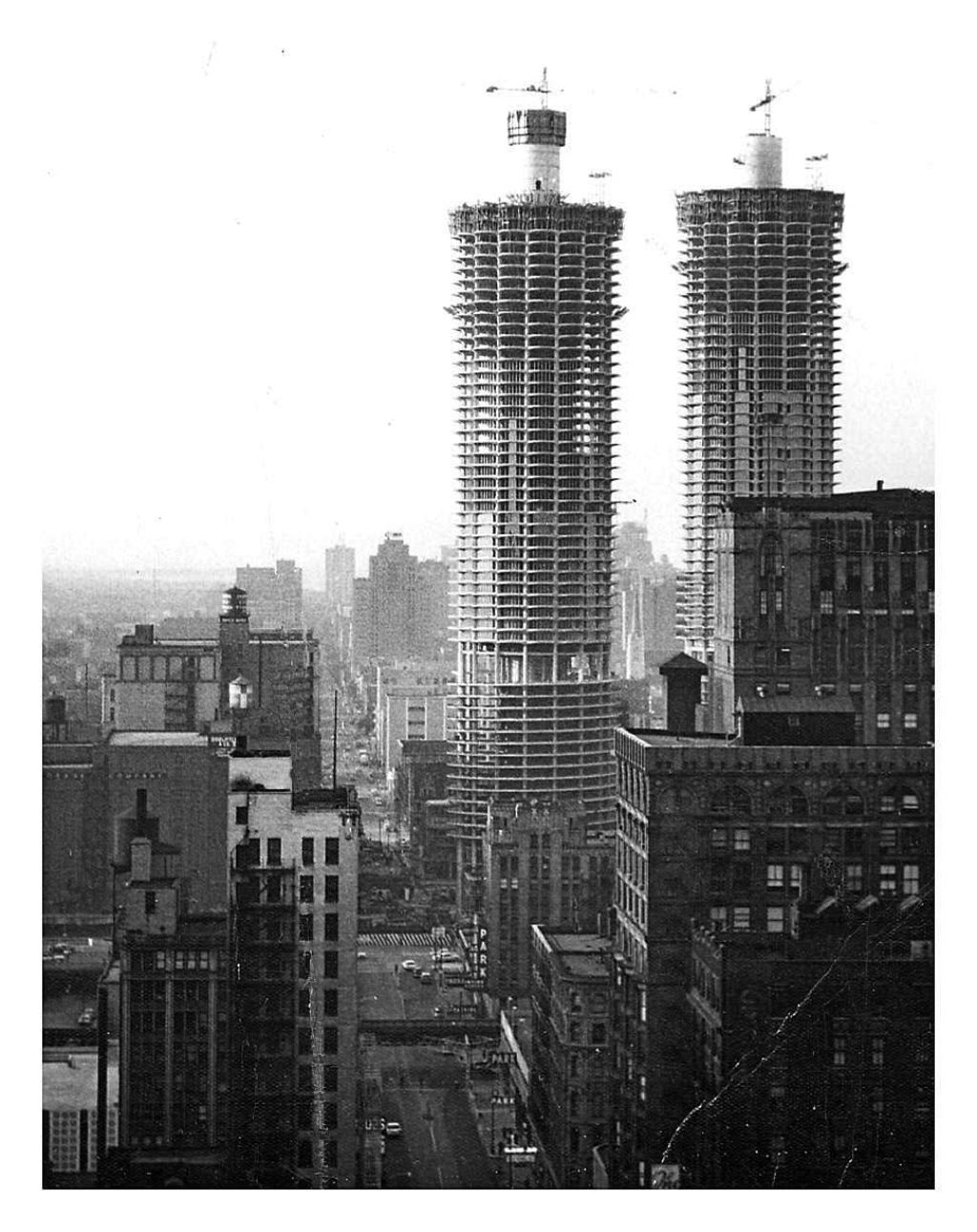

Marina City was the most ambitious residential project ever constructed in Chicago, crucially funded by Building Service Employees International Union seeking to reverse decades of “white flight”, the mass migration of white people from urban areas to post-war suburbs. Societal change, rather than profit incentives, was the primary driver of the project, and a radical solution to city living was required to sway public opinion in the immediate, and long term.

Conceived as a city within a city, the mixed-use complex accommodated a range of amenities including restaurants, a theatre, a bowling alley, and an office building within two 65 storey towers housing 1400 people, the tallest residential buildings in the world at the time of its completion in 1968. [2] Although dwarfed by some of its newer neighbours, they stand more than double the height of Dublin's tallest building at 179 meters, and are just shy of the Poolbeg Chimneys. As the first major mixed use complex in the USA, it inspired a boom of inner city construction that aspired to compete with the ease and amenities of the suburbs.

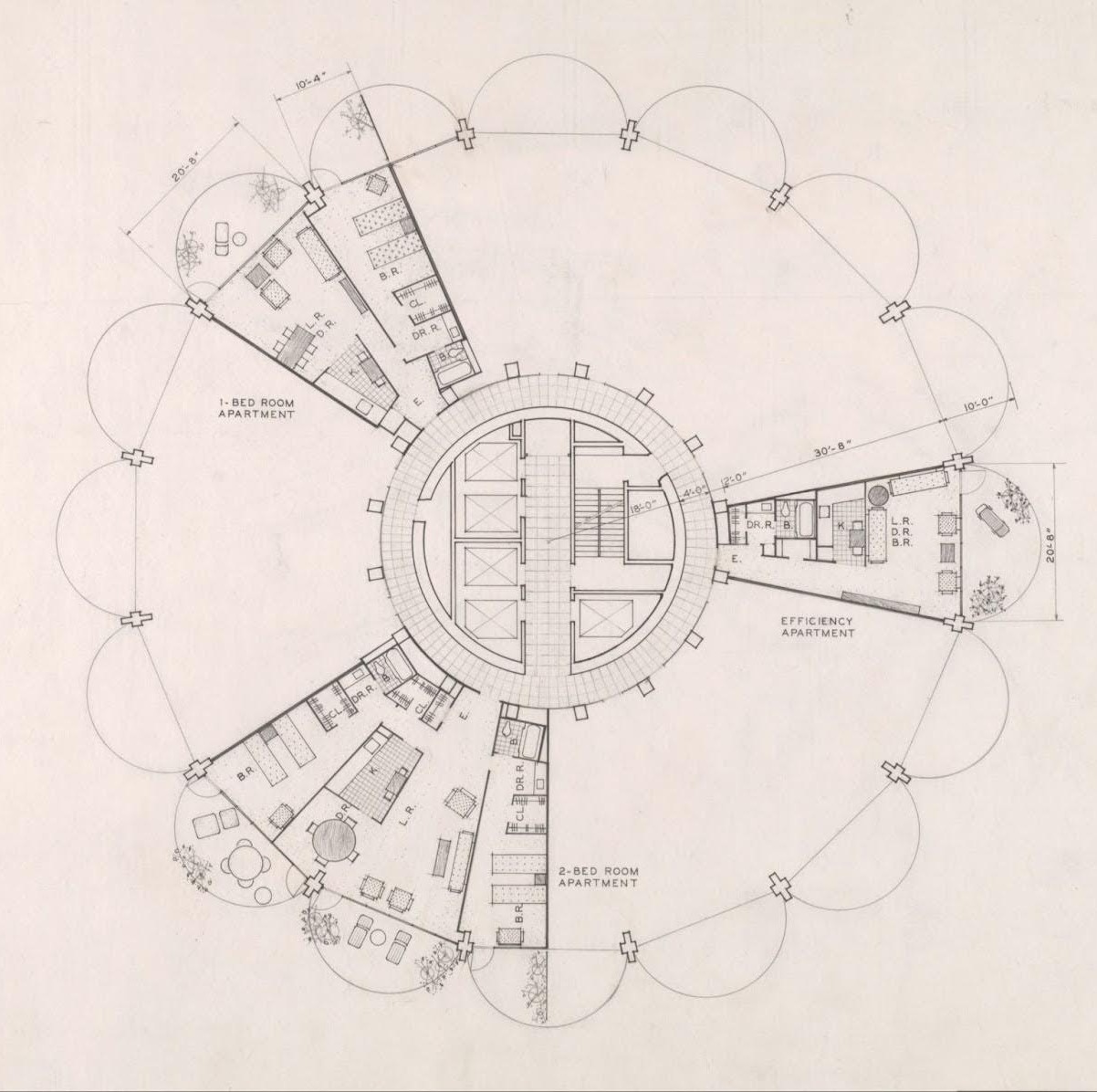

Right angles dominate Chicago; its unrelenting grid plan stretches for hundreds of square miles, and Marina City was a radical departure from the existing urban fabric. Once a student of Mies Van der Rohe, Goldberg broke from the rigid modernity of his former mentor, inspired by natural organic forms. The two towers share identical circular plans, rising from a spiralling base of open parking and topped with forty residential storeys. Each apartment radiates from the central core like a petal, culminating in a rounded balcony, giving the buildings their iconic flower shaped plan.

Creating lasting buildings also requires cultural sustainability, and the most sustainable structures are those that are appreciated. Marina City was immediately embraced by Chicagoans, becoming adored civic and mass media icons dubbed the “corn cob” towers. The towers appear tectonically simple yet sculpturally complex; a monolithic cast in-situ concrete frame with steel framed glazing slotted between, separating inside and out.

The structure holds the interior space, massive beams stem from the circular core, delineating living spaces. They sweep towards the floor at the building's edge forming columns, then arc into cantilever balconies in a display of structural grandiosity rarely seen in residential architecture. Completely rejecting Corbusier's free-plan, where structural elements can be completely freed from interior arrangements, here space and structure are in complete harmony.

Within this rigid frame is the flexibility to adapt to changing living standards. In our apartment, the antiquated enclosed kitchen has been opened up creating a single living space. The bathroom was enlarged and the black vinyl asbestos containing floor was replaced with a warmer hardwood. At 72m2, the comfortable apartment exceeds the minimum requirement for one bedroom apartments in Ireland by 60%, its irregular plan opening up to the strangely distant metropolis forty floors beneath. Neither sky nor ground are visible from inside, the city looms above and disappears from view below.

Residences are raised above 19 floors of parking – an unavoidable reality of 1960s America – and as the first major development in a declining industrial area, lifting the residential blocks may have given some relief from the smog and dust below. This conversely embodied a kind of “anti-urban” philosophy where multiple levels of parking dominate and “eyes on the street” are non-existent. The “city within a city” mantra perhaps becomes an island within a city. Despite its achievements, Marina City’s anti-pedestrian urban edge with moat-like level changes and large car ramps, removes any sort of meaningful presence at street level to non residents.

Although the area now bustles with restaurants, bars and apartments, it is far from atypical residential neighbourhood. Flanked on three sides by streets that have more in common with the M50 than most urban environments; six lanes of constant traffic, window rattling subwoofers and illegal drag racing and are common late night nuisances.

Connection between residents can also feel strangely isolating. Elevators are not conducive to forming relationships and the curving plan allows for interaction between neighbouring balconies but doesn't encourage either. These large balconies feel like an interpretation of the traditional American porch lifted into the sky, shaded relief from the summer sun, or sheltered hideout to watch colossal lightning storms roll over the great plains and crash into Lake Michigan. They also allow you to engage in the longstanding American tradition of watching your neighbours from the porch.

Looking across to the adjacent tower, presumably people are enjoying their balconies, but they are lost against the infrastructural scale of the complex. Voices drift across, a party far above, arguing below. If you look closely enough they start to emerge. A TV flickers on, they're watching Friends, “Brian” from the local bar waves over as he's brushing his teeth on his balcony, a couple shut their blinds after drinking a bottle of wine on the balcony. Like L.B Jeffries looking out his rear window, I wonder if I am the only one piecing these disparate stories together. The feeling is one of shared isolation rather than community, alone together high above the chaotic streets below.

That is not to say there is no community here. A thriving residents group exists if you decide to partake. Movie nights occur weekly, taking place on the roof deck in the summer months. Art talks, game nights and seasonal parties regularly fill the shared amenity space.

Irish perceptions of community are more parochial; passing neighbours at the front door, greeting the postman. While traditional domestic formations may be useful facilitators for chance encounters, it is naive to imagine that communities require a specific type of urban form to propagate. Communities are formed by longevity and security. Apartments here are privately owned or leased long term, but beyond that, residents are fiercely proud of their iconic modernist home. The ambition of drawing people back to the urban center was achieved by creating liveable homes. Many residents have been here for decades, some from its very inception.

Despite the abundance of new construction in Ireland, the race to the bottom of minimum standards and the prevalence of build-to-rent schemes prevents apartment living being seen as a viable long term option. The corporatisation of housing provides neither the long term security nor exemplary housing needed to form community or societal change.

Similar to the Irish housing crisis, urban dereliction in Chicago was an immediate problem that needed a swift response. The architects and – crucially – an ambitious funder, understood that an exemplary project was needed to shift societal attitudes, not a short term band-aid. Marina City stands as a testament that radical solutions can significantly alter public opinion and trajectory of an urban area. This kind of thinking is urgently required, and if we must look up and abroad for solutions, then let us ponder on the porches of Marina City.

In this article Dónal O’Cionnfhaolaidh reflects on high rise living, community, and the legacy of an architectural icon after four years of living in America's most ambitious residential project.

ReadWebsite by Good as Gold.