Recent debates around farmers, food production, and climate action have, at their core, a plethora of varying and conflicting imaginaries about rural landscapes, rural livelihoods, and an imagined divide with rural areas pitted against urban areas. In the provocatively titled article, ‘Townies v culchies’, Flynn and Lavin reference the culture wars unfurling around agricultural emissions reduction in Ireland in our preparation for a just transition [1]. Similar debates are happening right across Europe with media in the Netherlands recently drawing attention to this perceived binary. To have a just transition means to put in place the framework to support workers and communities susceptible to risk as we move towards a low carbon economy. Deciding what structures to put in place necessitates rupturing the rural-urban binary to achieve fresh thinking on the connection between rural spaces and urban centres. Problematically, as Flynn and Lavin astutely conclude, ‘the urban rural divide may only deepen in years to come’.

Whether we recognise it or not, people’s ideas about cities and urban centres are shaped by grievances, desires, and fears. Farmers travel to Dublin to protest in front of the government buildings they see as staunch representations of centralised power. Understandings of the urban are often reduced to ideas about high-density inner-cities juxtaposed with ‘remote’ rural towns and villages. And even though the ‘rural idyll’ is not accepted by all rural dwellers (nor all urban dwellers), it remains a strong geographical imagination that impacts where people choose to live, visit, and locate themselves.

Inherently, these bifurcated imaginaries are not a bad thing. Place and our surroundings shape who we are as human beings traversing variegated landscapes. However, what is problematic is the influence the rural-urban binary is having on shaping policies that impact our potential for a just transition. A just transition that incorporates decent jobs and a better quality of life appears to be a ‘no brainer’. Yet accomplishing this requires a paradigmatic shift in our historically entrenched and collective imagination about ‘the rural’ and ‘the urban’. It means accepting that, fundamentally, the rural and urban are inextricably linked and deeply interconnected. To negate and deny this complex relationship opens the possibility for problematic, fragmented policies. Alternatively, accepting this relationship and seeking ways to strengthen it will result in policies that enhance livelihoods and wellbeing for all.

This is already happening in some places. The Northern and Western Regional Assembly’s (NWRA) Regional Spatial and Economic Strategy (2018) embraces thinking beyond the traditional rural-urban divide to consider enhanced forms of interconnection. NWRA’s map of their sub-regions acknowledges existing links to Dublin as an urban centre and draws on them as potential ‘catchment’ areas to enable economic opportunities. While we would push for greater balance between the sub-regions and nearer, smaller urban centres (i.e. Donegal Town, Sligo, Letterkenny, etc.), the point is that regional flows exist – from our most rural spaces to urban centres – and these can and should be leveraged to produce more just futures.

At county level, there may be erroneous sentiments that ‘urban’ measures are foisted upon rural areas. For example, urban containment policies can be seen to be ‘anti-rural’, and yet, urban centres are key for farmers and food enterprises to access local markets and sell and produce locally. Pathways for a just transition involve diversification and re-localisation, to view interlinkages and value chains for farmers first in their local area, then in their nearest urban centres, and later larger metropolitan areas. Re-localising and focusing on value-added and shorter value chains requires integrated thinking, rather than silo thinking.

Examples of dependencies on the rural-urban continuum include: enhancing the dynamism and attractiveness of urban living to contain urban centres and maintain their vibrancy; improving broadband connection to expand remote working options and revive small towns and villages; and creating strong farm-to-city table access links through shared food processing units, farm shops, farmers markets, and market gardening to widen the farmer’s economic reach and sustain urban centres. However, enhancing and availing of this continuum requires appropriate policy, vision, finance, and placemaking support at both the local authority and central government level to attract people into towns and villages and open up markets and spaces.

To think about and foster a cohesive regional imaginary and bring the above examples to fruition, we need to acknowledge that urban and rural areas are both products and shapers of economic, political, and social processes that operate at varying scales. Yes, just transition solutions grow from place and, yes, local place-based solutions are important, but we need new imaginaries that also go beyond the ‘local’. Place is important in identifying just transition solutions but all parts of Ireland – rural, villages, small towns, and metropolitan areas – have different existing relationships to each other. New and existing organisations focusing on novel models of food production, forestry, and agriculture need flexible forms of support to cater for growth and creativity [2].

The scholar Yi-Fu Tuan (1977) has likened space to movement and place to pauses – stops along the way [3]. Our locations, locales, and our sense of place are hugely significant in supporting a just transition, but equally significant are the spatial flows of transport, infrastructures and investments. Rather than perpetuating an urban-rural binary in policy and identity, a just transition will be most effective when we adopt more dynamic and integrated approaches. Only then are we able to effectively answer the question of how farmers can be better supported by our urban centres. In doing this, we can also determine how best to support farmers as food producers and their continued identity as custodians of our landscapes.

Present Tense is supported by the Arts Council through the Architecture Project Award Round 2 2022.

1. V. Flynn and R. Lavin, ‘Townies v culchies: the new culture war in politics’, The Times, 31 July 2022. Available at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/townies-v-culchies-the-new-culture-war-in-politics-p6f6v6x99

2. N. Moore-Cherry, A. Clavin, T. Krawchenko, and J. Tomaney, Exploring Place-based Opportunities for Policy and Practice in Transition, National Economic and Social Council Research Report no. 24, July 2022. Available at: https://www.nesc.ie/publications/exploring-place-based-opportunities-for-policy-and-practice-in-transition/

3. Emeritus Professor Yi-Fu Tuan (University of Wisconsin-Madison) passed away in August 2022. Tuan has profoundly influenced the way scholars think about the relationship between people and their environment.

Effectively a continuous zoom call encased in a three-metre tall stone frame, the portal arrived with a promise of diasporic fraternity and a message of shared humanity borne out of access to the same ‘liveness’. The project is regularly described by Gylys in profoundly optimistic, even techno-utopian terms: ‘I felt a deep need to counter polarising ideas and to communicate that the only way for us to continue our journey on this beautiful spaceship called Earth is together’, and later as ‘The addition of the Portal in Philadelphia is an exciting step forward in our mission to build a bridge to a united planet’. [1] This sci-fi language of ‘spaceships’ and ‘missions’ – that suffuses all publicity released by Portals Organization – seems to reveal that for Gylys, the specific urban contexts in which the portals are located are secondary in importance to the fact that cities have dense populations, and can therefore bring a maximum number of ‘fellow humans’ into remote contact.

There is generosity in this goal. While Gylys may be operating from an idealised stratospheric viewpoint, the installations themselves are nevertheless embroiled in the fabric of urban life – in the politics of real estate, and bear witness to the endlessly contingent cityscapes they exist within. [2] Insofar as they present an image that is truly ‘live’, they live among us.

In fact, their circular viewport, coupled with their stationary nature, means that the portals share something of a cultural lineage with a much older technology of civic novelty: the camera obscura. Particularly the popular Nineteenth-Century camera obscurae that were built to be public attractions on high vantage points in cities like Bristol or Edinburgh. When spending time with the images cast by both, the presence of a hypnotic and uncanny liveness – an endless, voyeuristic potentiality – can make it difficult to look away for fear of missing something.

The portals differ from these darkened rooms however, because unlike the rarefied, sanitised views offered by these constructions they address the street at just above eye-level. In Skyline: The Narcissistic City, cultural historian Hubert Damisch outlines a divergence in the historical representation of urban space between ‘birds-eye-view’ depictions and maps that abstract and seek to rationalise cities – ‘Does the city remain “real” when considered from such distances [...]’ – and street-level depictions that present urban space as lived, contingent, and personal. [3] Damisch argues that the perspective techniques used by the painters Canaletto and Brunelleschi to produce realistic veduta paintings imply and demand a subject. [4] Veduta means ‘view’ in Italian, and there is no view without a viewer.

Camera obscurae are distinctive today for their relative stability. Unlike ubiquitous jittery smartphone video feeds, a camera obscura will generally remain still, allowing the world outside to move silently past within its static frame. A decision therefore needs to be made about what its aperture should be trained on. Will there be enough movement and visual interest from this or that vantage point? There is a politics of performative urban representation implied in this decision. What kind of scene, what view of ourselves and of our space justifies the building of a camera obscura? A similar value judgement applies to each portal.

Many Dubliners were initially bemused and apprehensive at the choice of location on North Earl Street. Sitting in the afternoon shadow of The Spire, and across the road from the GPO, it is placed in a historically significant part of the city, but also an area – ‘D1’ – that is notorious among locals for its high concentration of social issues. There was much talk at the time of; ‘why we can’t have nice things’, and the early weeks of the portal saw enough of what was deemed inappropriate behaviour from both cities to generate a viral international interest in the portal, and a temporary suspension of its video feed.

It is significant that it was placed in the heart of D1, rather than an alternative, more predictable cultural hotspot. Since its installation planters have been placed immediately in front of the screen, to create distance between the portal and the crowd, and the steady stream of visitors to the portal appears to be bringing a form of passive communal surveillance to the street, along with bringing custom to the area. Regardless of the location choice however, the important thing is that the portal greets us where life happens, at street level, rather than from on high. For this reason, and despite its sci-fi billing, it enacts a useful resistance to a pervasive trend in tech ideology to operate inter-planetarily, agelessly, and it ends up doing something simple – it enables eye-contact.

We’re looking at a street-level view of somewhere in the UK.

A woman in a black knee-length jacket does a shimmy dance in the centre of the circular frame while a group of tourists film her from our side.

Someone is on their phone waving into the screen, someone on screen – also on a phone – waves back.

We’re in Poland. But this camera angle seems to be more buildings than pavement and there’s no one in view.

Then, suddenly, we’re in Lithuania. An empty square, wet cobblestones and white street lines stretch off towards a grand seeming civic building.

There must be more than twenty people gathered here in the rain at this point, James Joyce’s hat and glasses standing only just taller than the cluster of black umbrellas.

The square is still empty, a man with a dog on a lead walks through the centre of the frame from left to right.

A young woman and man emerge from the bottom of the frame and turn to us while on the go, waving their bound umbrellas at us as if afraid of appearing rude.

It feels like we should see ourselves on the screen, as if we were taking a group selfie. We sense that we are performing, but we disappear at this end.

Lithuania is busy now. It is wet there too.

Three people here have not moved from their position at the front since I've been here. It feels like they are waiting for someone.

On our side a woman in a red velvet dress with a black umbrella pirouettes and curtseys while on her way into North Earl Street.

A seagull sits atop the portal.

In May 2024, the Lithuanian artist Benediktas Gylys installed a portal between Dublin and New York. In this article, Felix Hunter Green explores how the portal (the third of its kind at the time) introduced a new form of present tense, a remote urbanism, to the fabric of North Earl Street.

Read

Interdisciplinary gatherings are rare, yet extremely useful because they allow people from various fields to meet, exchange information, influence each other's point of view, and to learn from one another in a way which is unique, unpredictable, and dependent upon the nature of participants field of discipline.

For various reasons, art and design-specific interdisciplinary gatherings seldom occur. Firstly, artistic occupations are generally quite competitive, so may prove reticent to share their processes. It is unfortunate as I firmly believe the more artists that one surrounds oneself with, the more one can explore their own process, even more so when it comes to an international gathering of artists and designers who would not otherwise meet.

Secondly, artistic communities are usually formed by a group of people interested in the same form of art, which is certainly beneficial when it comes to improving one’s technique. Nonetheless, learning from someone who is focused on a different discipline, thus confronting an unexpected perspective, is extremely useful. For instance, a painter and a fashion designer are both interested in colours: comparing their approaches can be eye-opening and thought-provoking for both. Being so rare, when people from various countries, disciplines, and professions do meet it is unforgettable and extremely enriching.

One such opportunity is MEDS, ‘‘Meeting of Design Students’, an annual international event that unites creative students from different fields together with practising professionals to share knowledge and skills and form meaningful connections through collaboration the medium of hands-on innovative projects.

A platform for creative and cultural exchange

MEDS is an international, non-profit, two-week event. Although adored by many international students, it is usually only through word of mouth that one gets to hear about it. This article is intended to raise awareness of this event, as it is a unique opportunity providing a wonderful and enriching experience both for students and young professionals alike to learn new skills and meet like-minded people. MEDS brings together students from various creative fields as well as professional practitioners to share knowledge and skills – “It promotes design’s positive societal impact, fosters interdisciplinary collaboration, and offers designers a platform to build connections, unlock potential and apply their talents outside the faculty” [1].

MEDS began in 2010 and has been held almost every year since. It has been hosted in a different country every year: Ljubljana, Slovenia in 2012, Dublin two years after, and Zaragoza, Spain in 2022. The event usually spans two weeks in August and gathers around 150 participants from all over the world.

To attend, one has to fill out an application form and complete a creative task. If selected, you become a member of a ‘national team’ including about 10 people from each particular country. Every participant chooses one of the proposed projects and spends two weeks working on it. The philosophy of MEDS rejects any hierarchy and so the tutors, who are open-minded professionals volunteering their time, and the participants develop and shape the project outcome together.

Projects / Workshops

This year’s Meds revolved around Rijeka, the ‘City of Textures’. All projects were typically hands-on, site-specific, and responded to the city and its context.

For instance, a project called ‘Urban Outf***ers’ led by Iva Mandurić, Vili Rakita, and Lea Mioković was an opportunity to design one’s outfit, a personal urban equipment, a public space survival kit to inspire and possibly shape one’s environment as soon as it’s taken off and left in public space. Something that was originally personal and individualistic suddenly became a part of public space to encourage interaction.

Anyone with a project in mind can become a tutor. A project called ‘Fialaigh’ (a veil, screen, or cover) was led by three TU Dublin graduates. All three, Christan Grange, Stuart Medcalf, and Shane Bannigan, studied architecture at Technological University Dublin and came to Rijeka to guide a project that was focusing on ‘themes of vacancy, occupation, value, and ephemerality, using spatial installation and film and the interface between them to interpret, capture, express, and let emerge narratives in our work’, as the tutors put it.

Had one wished for a building and construction-related project, one could have chosen from at least two options. The ‘Black Thought’ project proposed by designer Çisem Nur Yıldırım and the practising, Barcelona-based architect Alberto Collet involved building a sustainable wooden pavilion inspired by the Japanese technique Shou Sugi Ban. The other option offered rammed earth construction and tile production linked to themes of migration.

‘Plivatri’ and ‘Rječina’ were projects that designed public space interventions including a floating wooden platform for about eight people to hang out on, and pieces of public furniture made of scraps found on a trash pile for people to sit, share, and interact. Two of the tutors for ‘Plivatri’, Leda and Ahmad, met during MEDS workshop in Poland in 2021. Leda is a Cypriot designer based in the Netherlands, and Ahmad is a Lebanese architect and urban designer with experience across Europe and the Middle East. Leda later met Stephanie (a Romanian industrial designer) during their studies in Eindhoven. All three are passionate about alternative paths and collaboration across different disciplines and therefore teamed up as tutors.

Last but not least, three Warsaw Polytechnic students were the tutors of the ‘Pop Of Colour’ project this year. Although Mateusz, one of the trio, has just finished a Bachelor’s in Architecture, he is a graffiti artist himself. Inspired by numerous murals all over Rijeka as well as its industrial heritage and sea-side views, the task was to co-design and paint a mural on one of the walls of the local school gym, make a few pieces of simple furniture, and design a few playground games. The playground and gym remained open during the day allowing local children to pop in and observe the work in progress.

The MEDS community firmly believes in involvement with local communities, and therefore organises guest lectures to foster the connection between international students and the whole community. From friendships, collaborations, and professional networks, connections built at MEDS last long after the event ends.

Living the MEDS experience

MEDS is a purely student organisation run by students, recent graduates, and young professionals (once participants themselves) who make the event happen year by year, advocating for this broader, collaborative approach. The whole event is organised by a different national team every year and is heavily reliant on various sponsors. Accommodation is usually simple; participants and tutors stayed in the local school in Rijeka. Surroundings are different every year, but enthusiasm, curiosity, and creative energy remain. As places at MEDS are limited, there is luckily a very similar organisation called EASA (European Architecture Students´ Assembly). Following the same principles, it is mostly attended by architecture students however. MEDS is an international multidisciplinary event for art, design, and architecture students as well as practising artists, designers, and architects to broaden their skills and develop creative ideas.

Above all, it is a wonderful opportunity to establish long-lasting connections between people, disciplines, and cultures in a cross-disciplinary, collaborative environment..

Interdisciplinary gatherings, and particularly those of an artistic nature, offer a great opportunity to learn in unpredictable ways by bringing together creatives from diverse fields. In this article, Kristýna Korčáková explores how the ‘MEDS’ programme provides this chance.

Read

Yet in Ireland today, the built environment is too often defined by crisis; housing shortages, vulture funds, stalled planning, delayed public infrastructure, and sprawling suburbs with inadequate public transport. Across these challenges, one pattern is consistent - people’s needs have been systematically sidelined in favour of economics. This raises two critical questions; how did people become invisible in planning, and how has this eroded public trust?

To contextualise this argument through a recent controversy, the proposed redevelopment of Sheriff Street has been presented as a scheme designed to ‘regenerate the area’ and tackle underdevelopment. Yet, Rainbow Park, a green space in the heart of Sheriff Street, remains untouched despite long-standing calls from residents to transform it into a vibrant hub. According to Mark Fay, chairperson of the North Wall Community Association, residents were also blindsided by the announcement, revealing how little meaningful consultation took place.

Urban theorist David Harvey has argued that regeneration often masks gentrification, where the well-being of current residents is sacrificed to increase property values. The office blocks and luxury apartments planned for Sheriff Street are designed for people largely ‘unindigenous’ to the neighbourhood, while those already living there risk cultural erasure. This is part of a larger pattern of gentrification dressed as renewal, sanitising inequality rather than addressing it.

So how might architectural practice move away from this cycle and begin to approach the built environment in a genuinely democratic way?

Public consultation has been offered as a solution, but in practice often amounts to little more than a box-ticking exercise. Public forums tend to come late in the design process, when decisions have already been made, leaving residents feeling duped. In order to truly facilitate democratic design, communities must be involved from the very beginning, when needs and opportunities are first identified. This must then be followed by genuine co-authorship, where residents have a real stake in shaping outcomes. And even this is not enough if architects and planners fail to develop empathy for the people behind the feedback.

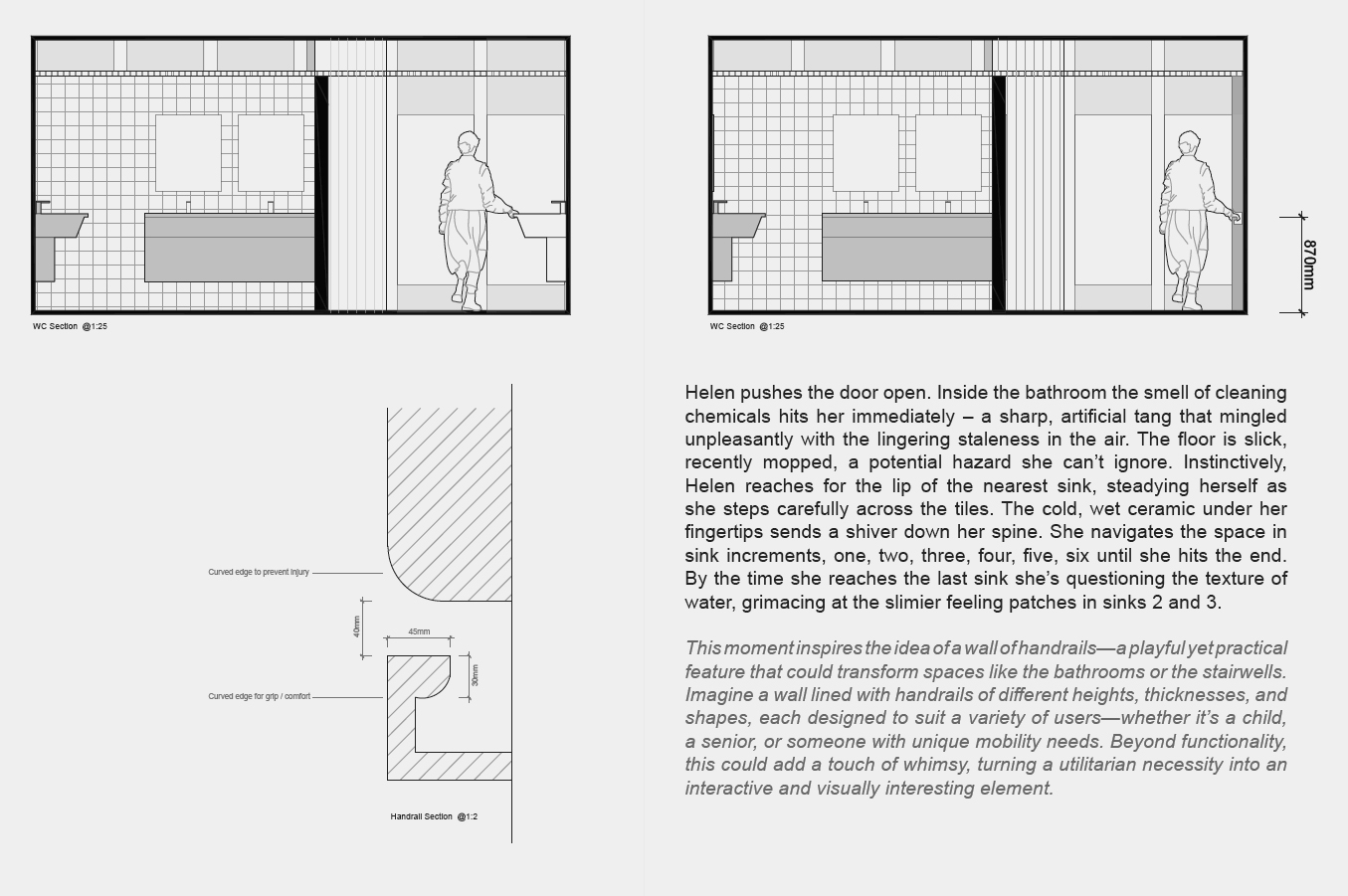

This is where the act of ‘writing people back into design’ becomes important. ‘Fictional Narrative Writing’ is a methodology that I have developed which merges writing, storytelling, and narrative empathy, helping designers to integrate people and identities into their work. This involves creating characters and scenarios drawn from what is learned in the early stages of design development, and then designing through their eyes. Imagine Susan, aged forty-six, recovering from a hip replacement, needing to move comfortably through a building or public space. Or Steven, aged sixteen, with little money and nowhere safe to gather with friends. How might a street, square, or public building serve both of them? By imagining these lived experiences, architects are forced to consider how spaces perform for different people, ensuring that those consulted at the start are not only listened to, but remain present and visible in every stage of design.

By embedding empathy in practice, designers begin to understand diverse people’s needs, desires, and vulnerabilities, while the public sees themselves reflected in the design process. This mutual recognition rebuilds trust, transforming the built environment from a top-down imposition into a shared project of social life.

Above all, this methodology requires us to acknowledge that architecture is never neutral. Every design decision is a social, and therefore political, decision. This is not a plea for grand gestures, or expensive experiments. Often, small interventions can transform how a space is experienced. A family-friendly bathroom that gives independence to children. A sheltered bench that restores dignity to those waiting for the bus. Free, accessible indoor spaces that provide refuge to teenagers who have nowhere else to go. Inclusive facilities that allow people to exist without fear of scrutiny. These are not luxuries. They are the basics of a society that values its citizens.

Ireland is at a crossroads. The choices we make now will determine whether the built environment continues to alienate, or whether it begins to reconnect people, and foster a sense of community. We can persist with Tetris-block developments dictated by developer economics, or we can restore architecture’s social purpose. The shift will not come overnight, nor will it come through tokenistic frameworks. It requires a change of mindset, to see people not as passive recipients but as co-authors of the places they inhabit. It requires putting dignity and a sense of belonging on equal terms with cost and efficiency. It required introducing empathy as a design tool.

If we succeed, trust can be rebuilt. Our cities and towns can become places of pride rather than disillusionment, and the phrase ‘built environment’ can return to its true meaning: the collective spaces where people live - and live well.

It is time to write people, community, and democracy back into Ireland’s built environment.

The built environment is defined by Oxford Languages as ‘man-made structures, features, and facilities viewed collectively as an environment in which people live and work’. Looking beyond the sexism, naïve assumptions of inclusivity, and the capitalist emphasis on perpetual labour engrained in this definition, two words stand out: ‘people’ and ‘live’. I highlight these words as a reminder of the purpose of the built environment, and for whom it exists. The built environment should be a proactive space that empowers people to live a comfortable, functional, and democratic life.

ReadWebsite by Good as Gold.